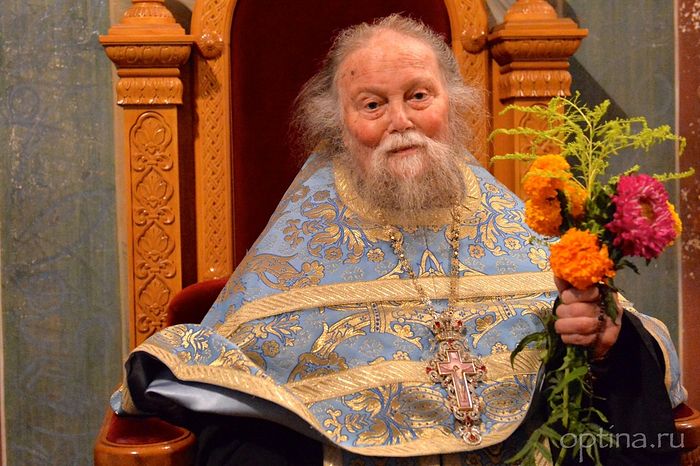

At 12:15 AM on January 22 of the newly-begun year, in a Moscow hospital, at the age of 78, peacefully reposed Archimandrite Benedict, who for twenty-seven years was the vicar of His Holiness the Patriarch, managing one of the most famous monasteries so beloved by the Russian people—Optina Monastery.

Exactly twenty-seven years ago, on January 20, 1991, on the day of the patronal feast of the Optina skete, consecrated in honor of the Prophet John the Forerunner, he arrived at Optina , taking on the administration of the monastery. The monastery had been left without leadership for half a year already by then, as its abbot Archimandrite Evlogy was in the hospital after a serious car accident. The monastery, given over to the Orthodox Church on November 17, 1987, quickly rose up from the ruins. It was the first of the monasteries opened under the Soviet Union (after Danilovsky Monastery—the residence of the patriarch of Moscow). There were already nearly forty brothers there, a strict monastic liturgical typikon, and the central Entrance of the Theotokos Church was already restored, as well as several brethren housing buildings and a partially destroyed fence. And although the remains of foundations and walls of other churches and bell towers could be seen, the problem was still much greater than hastily-patched holes—it was the time of a great spiritual upsurge, when the first shoots of spiritual life slowly began to sprout through the asphalt of godlessness.

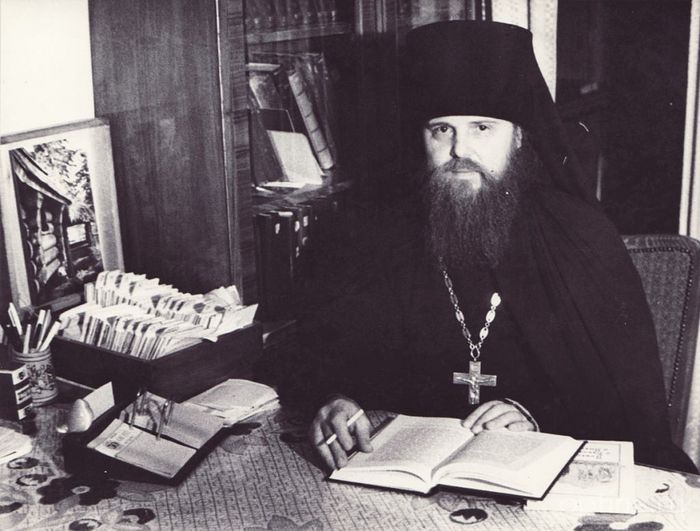

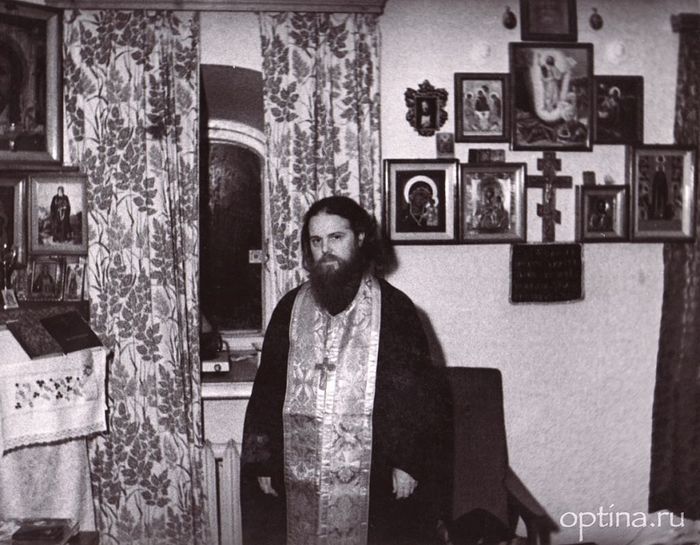

Archimandrite Benedict was an entire epoch in the life of our Church. The first half of his Church activity, the time of growth and spiritual maturation, passed within the walls of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra. He graduated from seminary there, and then the academy; he was tonsured into monasticism and ordained as a priest. He became a faithful disciple of Archimandrites Kirill and Naum there, communicating with them over the course of two decades, in his words, practically every day. There, together with Archimandrite Alexei (Polycarpov) he became one of the people’s most beloved confessors. Igumen Vissarion even composed a rhyme about him in the 1980s: “The Lavra has two pillars: Benedict and Alexei.”1

For many years, Igumen Benedict would hear confessions for several hours every day in the gate Church of St. John the Forerunner, where his numerous spiritual children would come. After trapeza he would receive those who were in need of more prolonged conversation in the gatehouse at the entrance or in his cell. Besides confessing, he fulfilled several other important obediences: He was the monastery’s main accountant, librarian, and mailman, and he sang on the kliros. A year before his appointment to the position of the abbacy of Optina Monastery, he was appointed as the head of the Gethsemane Skete and began to resurrect it from complete desolation.

There was a great deal of discussion in the diocese’s search for an abbot for Optina—after all, in some ways this position was much more responsible than many episcopal sees. Fr. Benedict has said that he himself had great doubts, seeing all the difficulties of the ministry that stood before him. But the elders, the spiritual fathers blessed him and sent him to Blessed Lyubushka in Susanino. She said, “Yes, Benedict, it can be Benedict.”

At first Patriarch Alexei II offered him a choice: Either abbot in Optina or confessor in Diveyevo. Fr. Benedict immediately realized that he was no longer able to bear the burden of confession: He had already overstrained his heart and felt that it would not endure long. He chose Optina.

Moreover, his health was in a depressed state. Fr. Benedict himself didn’t understand how he could lead such a monastery. His asthma attacks had recently been so severe that he could only sleep sitting up, he would begin to gasp as soon as he began to speak, and he couldn’t finish the exclamations in the services. But the patriarch said that the Lord would strengthen him. And on the very first day of his arrival to the monastery, Father was surprised to notice that he didn’t need his inhaler at all, which he didn’t used once since that day, even though he had to use it multiple times a day at the Lavra. And the breathing exercises that he persistently, day after day did in his cell led to his voice finding such strength and volume as allowed him to pronounce his exclamations and homilies such that every word was clearly heard in every corner of the church. Thus the will of God was carried out—the Optina abbot often remembered this when it became unbearable for him to manage the monastery; but he did not resolve to ask for retirement.

The patriarch elevated Abbot Benedict to the rank of archimandrite, and, having celebrated the feast of Theophany in his home monastery, he left for Optina. At fifty-two years old, the abbot began a new phase in his life. Although his life “with St. Sergius” was filled with considerable labors and asceticism of self-denial and sacrificial love, the forthcoming activity was not an elevation, not a step to a Church career, but a severe cross, accepted by him for the sake of love of Christ.

Having become the abbot, Fr. Benedict stopped confessing his spiritual children about two years later, because he felt the combination of his responsibilities as abbot and as spiritual father were beyond his strength. But while recommending that they choose a spiritual father for themselves, he didn’t renounce his fatherhood in the spirit and in extreme cases always received and resolved the problems of his children, answered their notes, and most importantly—he did not abandon his prayers, which they felt with undeniable force. Archimandrite Naum said that Fr. Benedict bears his spiritual children in his very heart. Behind these words, simple at first glance, stands a labor of faith, of the deepest responsibility and compassion of his broad, wise heart.

The personal podvig of prayer is most often hidden from people, but in Fr. Benedict, behind his external severity and extreme concentration, was always felt the unceasing prayerful standing before God. Not by his external position, not by his rank, but by his inner magnitude this short-statured man was always noticeable in any company, even among people of much higher position. The secret podvig of nighttime prayer, which Fr. Benedict had already begun at the St. Sergius Lavra, was not abandoned afterwards. Due to his health, he gradually stopped going to the brothers’ Midnight Office service, and didn’t go to church every day, but the action of the Jesus Prayer was often imprinted in the features of his face, and the thin string of wooden beads, it’s loop spanning his hand, constantly moving. He developed this type of prayer rope himself while at the Lavra and made it with his own hands, even sending them to Athos at the monks’ requests.

It can’t be said that the then-existing brotherhood of the monastery readily accepted the new abbot. He was too different from the previous Archimandrite Evlogy (who subsequently became the metropolitan of Vladimir). The strong-willed Fr. Benedict who was not especially in need of advice changed the liturgical typikon and began to guide the whole way of life of the monastery to resemble that of the St. Sergius Lavra, where he had spent the larger part of his life. Some of the previous monks left Optina in the first half-year, and some left later. It was a difficult stage of growing up, like adolescence, which largely replaces the bright and inspired period of childhood. The abbot had to endure several severe trials: the tragic murder of three monks on Pascha in 1993, and the loss of other faithful helpers and brothers. It would be impossible even with many words to describe all the difficult temptations and the enemy’s invisible opposition to the life of the monastery.

But the monastery, glorified by the life of the great Optina elders, far removed from major cities, attracted many who were seeking true monasticism. Although monasteries were gradually beginning to revive everywhere, Optina was not lost in the crowd, becoming a powerful, world-famous monastery. The churches, bell towers, and other buildings were rebuilt and raised up from the ruins, and unique granite bridges were laid. The churches were given a magnificent look and new frescos and were filled with utensils, exquisite carved decoration, and icons. Between two and five Liturgies are served here every day, and the services are distinguished by a special reverence and austere monastic beauty, and strict and unhurried prayerful singing. The number of brothers exceeded 220 last year, and the number of pilgrims increases with every year.

Thirteen Optina elders and several New Martyrs and Confessors of the monastery were glorified during Fr. Benedict’s time. They managed to find the relics of ten elders that had been desecrated by the atheists. Several ascetics and confessors buried in various places were reburied in their home monastery. The hagiographies and works of the elders and research and recollections dedicated to Optina Monastery were published.

One of the main features that determined Archimandrite Benedict’s whole path was his fiery zeal for the faith. The deepest reverent faith determined all his successes and numerous achievements. He was a true zealot of piety with a caring heart. Demanding evangelical purity and sincerity from others, he himself always gave an example of extreme reverence for holy things. The services he celebrated will remain in everyone’s memory—ceremonious, unhurried, full of regal solemnity and prayerful at the same time.

Faith was the most important treasure of his soul. He so loved the truths contained in the treasury of the Church, often with childlike straightforwardness sharing some thought he had read in the Holy Fathers or in Scripture. Turning this acquired treasure over in his mind for several days, he would be amazed and ponder, and sometimes develop these thoughts, now astounding everyone around him with newly-revealed facets, now to the contrary disturbing them with some bold conclusion that would go against the Church’s teaching. It was not a far-fetched fantasy, but a deep, living experience; he lived by it. We could have omitted writing about it, preserving some formal correctness of hagiography, but it’s better to try to see these peculiarities for what they were rather than, keeping quiet, to cover him with a veil of half-truth.

Being a creative person, Fr. Benedict sought to make everything as good, beautiful, and sensible as possible. It’s enough to recall what clashes and disputes led to the approval of the sketches of the churches, the murals, the installation of icons in the churches, and the approval for the building of new buildings! He intervened in everything: in the work of the engineers who poured the foundation, in the designs of the architects who proposed drawings of the churches, in the publishing works and the designing of books. It wasn’t always successful and it often disturbed the work. He would approve, then decide something different, changing his blessing many times. However, all of these questions were not external for him, but deeply significant, inasmuch as he felt responsible before God for them. It was difficult to work with him, but in this was the manifestation of his indefatigable desire for perfection.

In his understanding of particular theological questions, he sometimes crossed the line, searched, pondered, and sometimes got carried away and faltered. But time passed, and he listened to the opinions of those who tried to cautiously correct him, and then, albeit with some reluctance, he would abandon an idea that seemed so beautiful to him, as it was not in harmony with the truth of the Fathers.

He was a strict pastor, often not pitying his spiritual children with external human condescension, but placed them before the uncompromising judgment of the Gospel truth. Those looking at the life of the monastery from outside would often express their sympathy to the brothers that they live in such strictness; sometimes the monks themselves did not refrain from murmuring. But, passing through a variety of temptations, many understood how necessary and fruitful Fr. Benedict’s exactingness was. For all the severity and seeming despotism, the abbot never trampled on the human personality. He could be very sharp and impartial, regardless of the order and age of the person, in some situations expressing his observations and punishing for misconduct. But that was Father’s zeal—zeal of soul—not accepting any negligence, laziness, or guile; zeal, burning not to cause pain, but to correct and heal a person, to make him understand the seriousness of life and his responsibility for his soul. It’s no wonder that some of his favorite words from Scriptures were, Cursed be he that does the work of God with negligence (Jer. 48:10).

It was possible to notice that Father, punishing someone, would then closely watch how that person bore his rebuke or flash of anger. If he saw that a brother received it all with humility, his soul so sincerely rejoiced that he even had to restrain his joy, although with difficulty. If someone received his thoughts and was offended, then Fr. Benedict made a considerable effort to reconcile with him another time, trying to make a joke, to smooth out the negative impression that had developed in the brother. He often repeated: Be angry and sin not. Everyone who trusted him felt his soul, that it was not indifferent to him, that there is not just human passion active here, love of power or ambition, but fatherly zeal for salvation in God.

Fr. Benedict was distinguished by the special gift of discernment. He attached great importance to it, saying that even if someone makes a mistake in making some kind of decision, if he reasoned and made considerable effort to learn the will of God, how to proceed properly, then the Lord will not inquire of him for his mistake, but will Himself correct its consequences. Contemplating some thought, he often returned to it, suggesting first one argument, then another, viewing it from completely different sides, and constantly prayerfully turning to the Lord for correction. Because of this, the solution to several issues, seemingly elementary, dragged on for a long time, but no one could reproach him for being hasty or superficial.

In recent years, Father greatly changed: Nearly all his previous severity left and reincarnated as benevolence and wondrous geniality. This change is explained by the fact that the mask of external strictness was no longer necessary; his soul had achieved internal freedom, and revealed itself to people in that fullness which earlier was inaccessible to the eyes, or slightly opened but for a time. It was especially brightly visible not in business situations, but in moments of rest. Every day, health allowing, Fr. Benedict found time to go to the stables. Interaction with the horses was a break for him that people didn’t give him in their continual flow, rushing to him for a solution to this or that problem. Brushing the horse’s manes or feeding them bread, he often joked, relaxing from the eternal tension, and sometimes even sang. And the horses felt the warmth and kindness that emanated from him. Many guests of the monastery and the brothers would come to the stables to talk with him in an informal setting. It was known to everyone that no better time for talking with Father could be found than at the stables. Although he “was resting from people,” he resolved many issues there. “The horses are quiet, and you all talk and talk,” he would joke.

By his participation in all aspects of the life of the monastery, in every detail, he took upon himself the unbearable burden of responsibility. He could not do otherwise, but it’s no surprise that he was often exhausted under its weight. Being a man of remarkable will, he did not dare to shirk his responsibility as he understood it. Idleness was completely foreign to him; he constantly lived with the problems of the monastery and of other people. In the afternoon he allowed himself at least a short rest of twenty to twenty-five minutes, and in recent years sometimes up to an hour, and he would go out to the stables a time or two. His existence was divided between the feasts, when he would unfailingly be at the services, and daily labors, which usually began at 8:00 AM and finished only at 11:00 PM, when he was finally able to be alone in his tiny cell.

He was a man of a departing era. There was no luxury or excess in his existence; he was free from avarice or any kind of acquisitiveness. He continued living in an unrepaired building the whole time, the oldest in the monastery. He long resisted those who wanted to “reseat” him into foreign cars on business trips to Moscow. He did not like traveling abroad and basically did not travel anywhere, spending the vacation blessed for him by the patriarch at Lake Seliger in leisurely fishing. He would usually set out alone in a boat for the whole day, leaving his attendants and basking more in prayerful solitude than in fishing itself. The abbot’s food was simple, although it was quite varied in recent years due to his poor health. However, he never tolerated violations of fasting days, although doctors often insisted upon it.

As an experienced pastor, Father created an entire system of education for the brothers. Seeing that city dwellers, especially the youth, were inherently infantile, egotistical, and lacking initiative, Fr. Benedict led newcomers through labor obediences in the barn, the stables, the hen houses, and other agricultural facilities, where over time he would pinpoint a man’s diligence, and his spiritual qualities would be revealed. “Don’t hide how a man relates to a horse, and how it reacts to him,” he loved to repeat. “If the man has a hidden defect, the animal will immediately sense it, and that man may not even admit it to himself.” He devoted a lot of attention to new novices and candidates for the brotherhood. Being limited in movement by his health, he would call the brothers to his cell and talk with them thoughtfully, trying not to overlook anything important from their former lives, and trying through prayer to understand the place of a specific person in the Church, and his personal character.

The situation in modern monasteries is such that the abbot bears the load of purely external administrative management of such a complex organism. There is therefore a danger that the “external” financial-economic questions, participating in the long services, and unavoidable communication with the powers that be and guests of the monastery did not leave the abbot any time for the inner, often highly complicated questions of the spiritual state of the brotherhood. The number of brothers at Optina has multiplied immensely, and the abbot introduced a specific system of “eldership,” where confessors experienced in the monastic life chosen from among the brothers are responsible for ten to fifteen brothers. Confessing the spiritual children handed to them, the spiritual fathers solved the emerging multifarious perplexities with the abbot himself, who, summoning them regularly, would ask them briefly about who lived how, and he himself confessed only the spiritual fathers.

Such a system can take the form of subtle “informing,” but Fr. Benedict never intended to enslave someone to himself—he only wanted to help him overcome various passions. For the most serious misconduct, the confessors would prompt the monk himself to go reveal the act to the abba of the monastery, who, in admonishing the offender in a fatherly way, would impose a penance upon him if he deemed it necessary. It was amazing that with the brothers’ most severe offenses, with the corresponding repentance, Fr. Benedict did not apply a penance. The sin itself was the weight that the transgressor bore.

In recent years, when the building and restoration of the walls of the monastery began to draw to a definitive close, Fr. Benedict began to devote more attention to questions of the internal life of the brothers. He, as a man deeply immersed in church life, was very disturbed by the lukewarmness and deep indifference even among those who had come to devote their lives to God. Requiring strict adherence of discipline in going to the services, he willingly went to meet the sick who had to miss the services, but in other situations, calling to account even for a minute’s delay. He would often repeat that the Lord sees everything, and if someone was disingenuous, citing sickness and avoiding Church prayer, then God would certainly send him a sickness, desiring to heal this sin.

Desiring to stir up the fear of God, Father introduced the obligatory study of the commandments of Sacred Scripture. Pocket-sized books with selected Scriptural texts were compiled, which every brother of the monastery had to memorize by heart. This knowledge was checked by Fr. Benedict and the brothers appointed by him. Although this method could be called largely scholastic and formal, he helped those who had no desire to study the Scriptures on their own, and to often immerse their minds in its living and everlasting Word. From the way that Fr. Benedict would pronounce some phrase from Scripture with such inspiration, it was obvious how much he himself was vivified by this word. He tirelessly persuaded others that it was necessary to memorize so as to constantly have it with you and to truly comprehend the reading; and knowing—to fulfill.

Love and attention to the Word of God were innate in him from his youth. When immediately upon graduation from vocational school, Volodya Penkov began working, the master craftsman gave him to read the New Testament in one night, asking him to return in the morning. Arriving home, Vladimir decided not just to read it, but to write out the Gospel. He didn’t sleep at all, and throughout the night wrote out the Gospel of Matthew and several of the apostolic epistles. The next morning, he brought the book to the master. “Well, did you read it?” he asked, extremely surprised when the youth showed him his work. The master was amazed and couldn’t believe him, and for a long time just silently flipped through the notebook. Then he decided to give him the book. Later, alone in nature, having chosen a picturesque place, Volodya took the New Testament with him and sat down to read it.2

Having amazing chastity from his youth, sometimes during Confession Father couldn’t understand the damage done to someone by some sexual sins, sometimes even expressing this out loud before the brothers near him. As a man of the old generation, he absolutely could not stand the liberty in clothing, the partial nudity, and the wearing of pants by women so prevalent today. When he saw something like it, a zealous spirit was ignited in him, the spirit of a prophet, like Elijah, and he would mercilessly castigate this vice in his homilies, seeing in it a terrible diversion against the chastity of the soul.

Besides his homilies, which he always gave without notes and with true inspiration, father held Sunday talks with pilgrims and the workers who permanently live at the monastery. A venerable elder made wise by experience, he tried to convey it to others at least to some degree. He often sprinkled his teachings with jokes, trying to make them more accessible and understandable. His pastoral zeal would not allow him to shirk these conversations, even when his hearing became much worse and he was unable to move without assistance.

We have yet to evaluate the spiritual greatness of the reposed abbot of Optina Monastery, having looked in a new way at this spiritual giant and pious and unfeigned servant of God who has crossed the boundary of eternity.