| Previous day | Next day |

| Old Style

January 24

|

Friday |

New Style

February 6

|

| Fast-free Week. Tone 1. | Fast-free period.

|

![]() St. Xenia of Rome and her two female slaves (ca. 457).

St. Xenia of Rome and her two female slaves (ca. 457). ![]() St. Xenia of St. Petersburg, fool-for-Christ (19th c.).

St. Xenia of St. Petersburg, fool-for-Christ (19th c.).

Martyrs Babylas of Sicily and his two disciples Timothy and Agapius (3rd c.). St. Macedonius, hermit of Mt. Silpius, near Antioch (ca. 420). Translation of the relics of Monk-martyr Anastasius the Persian (7th c.). St. Gerasim, bishop of Perm (ca. 1449). Martyr John of Kazan (1529). St. Sophia, first abbess of Shamordino Convent (1888).

Martyrs Paul, Pausirius, and Theodotian, of Egypt (3rd c.). St. Felician, bishop of Foligno in Italy (254). St. Philo, bishop of Carpasia on Cyprus (5th c.). St. Lupicinus of Lipidiaco (Gaul) (500). St. Zosimas of Cilicia, bishop of Babylon in Egypt (6th c.). St. Neophytus the Recluse, of Cyprus (1214). St. Dionysius of Olympus and Mt. Athos (1541).

Repose of Bishop Nektary (Kontzevitch) of Seattle (1983).

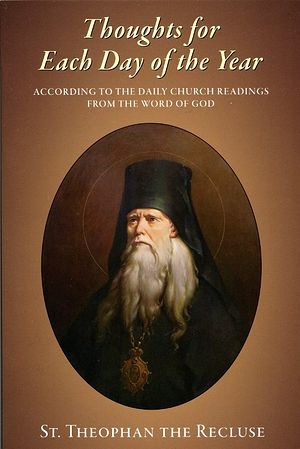

Thoughts for Each Day of the Year

According to the Daily Church Readings from the Word of God

By St. Theophan the Recluse

310

Saturday. [II Tim. 3:1–9; Luke 20:45–21:4]

Who are those having a form of godliness, but denying the power thereof? (II Tim. 3–5). Who are those others, ever learning, and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth? (II Tim. 3:7). The former are those who maintain all the external routines in which a godly life is manifested, but who do not have a strong enough will to maintain their inner dispositions as true godliness demands. They go to church and stand there readily. But they do not make the effort to stand with their mind before God continuously and to reverently fall down before Him. Having prayed a bit, they release the reins of the control of their mind; and it soars, circling over the entire world. As a result, they are externally located in church, but by their inner state they are not there: only the form of godliness remains in them, while its power is not there. You must think about everything else in this manner.

The latter are those who, having entered the realm of faith, do nothing but invent questions—“What is this? What is that? Why this way? Why that way?” They are people suffering from empty inquisitiveness. They do not chase after the truth, only ask and ask. And having found the answer to their questions, they do not dwell on them for long, but soon feel the necessity to look for another answer. And so they whirl about day and night, questioning and questioning, and never fully satisfied with what they learn. Some people chase after pleasures, but these chase after the satisfaction of their inquisitiveness.

Friday. [I John 2:7–17; Mark 14:3–9]

The world passeth away, and the lust thereof (I John 2:17). Who does not see this? Everything around us passes away—things, people, events; and we ourselves are passing away. Worldly lust also passes; we scarcely taste the sweetness of its satisfaction before both the lust and the sweetness disappear. We chase after something else, and it is the same; we chase after a third thing—again the same. Nothing stands still; everything comes and goes. What? Is there really nothing constant?! There is, says the Apostle: he that doeth the will of God abideth for ever (I John 2:17). How does the world, which is so transient, endure? Because God so desires that the world endure. The will of God is the world’s unshakeable and indestructible foundation. It is the same among people—whosoever begins to stand firmly in the will of God is made steadfast and firm at once. One’s thoughts are restless when chasing after something transient. But as soon as one comes to his senses and returns to the path of the will of God, his thoughts and intentions begin to settle down. When at last one succeeds in acquiring the habit for such a way of life, everything he has, both within and without, comes into quiet harmony and serene order. Having begun here, this deep peace and imperturbable serenity will pass over to the other life as well, and there it will abide unto the ages. Amidst the general transience of things around us, this is what is not transient, and what is constant within us: walking in the will of God.