Many Protestants and Roman Catholics are unfamiliar with the use of icons in church services or private devotions. In Orthodoxy they play a major role in both, but this role has often been grossly misunderstood. Because Protestant theology eschews many of the older Church traditions that explain the reasons and importance behind these religious images, most Protestants are unaware of their theological importance, believing them instead to be distractions from worshipping God. The perspective I’ve heard from most of my Protestant friends is that “having so many ‘faces’ in a church distracts from worshipping God.” Others tell me that images of the Blessed Virgin, saints, and angels are either idolatrous, or simply “unnecessary.”

I would say that one person’s standard of what is “necessary” and “unnecessary” for proper worship is as subjective as the next person’s, and that is why respect for the Church’s revealed teachings on these matters and a willingness to evaluate and consider the role of centuries of Tradition (including the writings of many prominent Church Fathers, both Latin and Greek) is crucial here. To disregard all this wisdom as “unnecessary” or distracting seems to me to be taking a great liberty.

St. Germanus, mentioned earlier, was Patriarch of Constantinople until iconoclast Emperor Leo III “the Isaurian” (r. 717-741) removed him due to the archbishop’s continued and vocal support for the veneration of icons. St. Germanus’ defense of icon veneration is most clearly expressed in a letter he wrote to John of Synades, in which the Patriarch states that

It is not to deviate from the perfect worship of God that we allow the production of icons … For we make no icon or representation of the invisible deity … But since the only Son Himself, Who is in the bosom of the Father, deigned to become man, according to the good will of the Father and the Holy Spirit, since He became a participant in blood and flesh, like us, as the great apostle says, “Having become similar to us in everything except sin” (Heb 4:15) we draw the image of His human aspect according to the flesh, and not according to His incomprehensible and invisible divinity, for we feel the need to represent what is our faith, to show that He is not united to our nature only in appearance, as a shadow … but that He has become man in reality and truth.

As St. Germanus writes, our icons never depict God the Father, since He is invisible, as Scripture tells us in many places, most specifically in John 1:18 that No man hath seen God [the Father] at any time.

Any Orthodox or Catholic theologian will tell you that veneration of saints’ relics or icons (known as doulia in Greek) differs significantly from latreia, which is the form of worship due to God alone. In our veneration, it is not the images or relics themselves we honor, but the grace of God in them. Doulia of icons and relics retains widespread practice in certain Catholic communities, particularly in South America and Southeast Asia, yet among American Catholics the practice is rare, mainly confined to older faithful, especially those who prefer to use the current Extraordinary form of the Mass, widely known as the Tridentine rite. Neither Catholics nor the Orthodox worship icons, nor do they worship the saints whose assistance they sometimes seek or whose exemplary qualities they seek to follow. This is of course a point of great distinction between Protestants and the older two Christian branches.

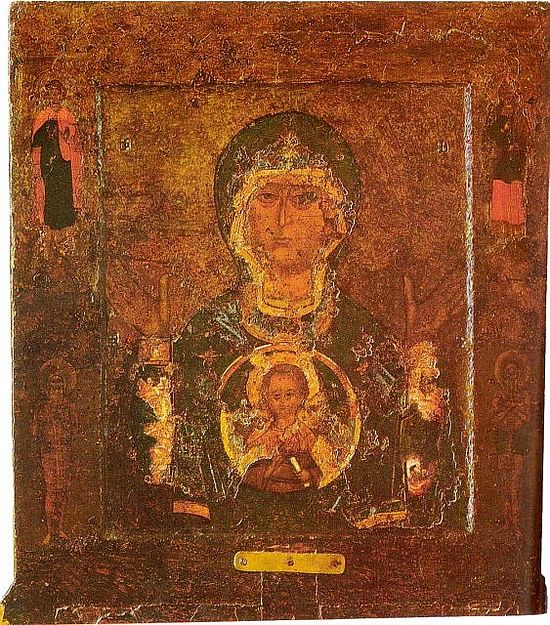

Many of the most famous icons are centuries old and have been attributed to saving certain countries or peoples from disaster, such as Our Lady of the Sign in Russia, which the Russian people to this day venerate for the role attributed to it in saving the city of Novgorod from invasion. Another famous, beautiful icon is known to the Orthodox as the Virgin Theotokos (Mary) of the Passion (familiar to Roman Catholics as Our Lady of Perpetual Help, it is given particular veneration among Filipinos.) The Passion icon is one of many healing icons, as many laity and clergy have reported being healed of their afflictions while praying in front of it. This might seem superstitious to some Protestants disinclined to look favorably on such veneration in the first place, but the records and claims of people claiming miraculous healings exist.

Regarding the Virgin Mary, the Orthodox give her several titles corresponding to her role as Jesus’ mother. Because she is Christ’s mother, she is therefore mother of the Son of God who was Himself One of the Holy Trinity “before all ages”. This is why we call her Mother of God, for she is the mother of the eternal Word, the Logos described in the opening of St John’s Gospel. The Church’s reasons for honoring Mary are quite simple, and they are Biblical. In Luke 1:43 Elizabeth calls Mary the mother of my Lord. Fr. Alexander Schmemann (1921-1983), Orthodox theologian and former Dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary, observed that Mary is “our link to Christ, and in Him, to God” the Father. She is

The very expression, the very depth of man’s “yes” to God in Christ … the human person that has become totally transparent to the Holy Spirit. If Christ is the “icon” of the Father, Mary is the “icon” of the new creation, the new Eve responding to the new Adam, fulfilling the mystery of love … Mary is the image and the personification of the world.

Thus, Mary is the natural archetype for mankind, a perfect example for her fellow human beings to imitate. Through her willingness to bear the Savior of mankind, full cooperation with the will of God became something attainable and personal for mankind. Because “she is the one who gave Him His human nature, His flesh and blood, she is the one through whom Christ can always call Himself “The Son of Man.””

Because of Mary’s willing cooperation with God

Salvation is no longer the operation of rescuing an ontologically inferior and passive being; it is revealed as truly a synergeia, cooperation between God and man. In Mary, obedience and humility are shown as rooted not in any “deficiency” of nature, but as the very expression of man’s royal freedom, of his capacity freely to encounter Truth itself. In the faith and the experience of the Church, Mary truly is the very icon of “anthropological maximalism”, its eternal epiphany … In Mary, the very notions of “dependence” and “freedom” cease to be opposed to one another as mutually exclusive. We are inclined to think that where there is dependence there can be no freedom, where there is freedom there can be no dependence. She, however, accepts, she obeys, she humbles herself before the living Truth itself, a Presence, a Call so overwhelmingly evident.

Because of Mary’s “yes” to God’s invitation to bear Christ the Savior, she signaled the coming redemption of humankind through her Son. No longer was man cut off from God, for God would enter the world through a woman’s body. Mary did not have to accept the role to which God called her; her very acceptance radically changed God’s relation to humankind, for it is through Mary that God entered the world as a man, and it is due to Mary’s humanity that Christ is “fully man” while also being fully God. Due to her special role as the Mother of Christ, it is only logical that

Mary stands in the very center of the Church’s vision of the world, of man and life as the ultimate fruit and therefore the highest expression of that humility and obedience, without which there is no entrance into the mystery of man’s true communion with God.

Fr. Alexander affirms her role as mediator and channel between man and God: “Truly she is unique … and yet she is one of us, she is like us: her life and her experience are fully human.”

This is why the Orthodox feel such comfort in the presence of Mary, why we can approach her with our prayers that she might intercede with her Son to save us. She is the natural maternal figure for all humanity to look to for comfort, and through her Son, the very vessel by which the promise of salvation came to our fallen world.

Many Protestants consider the veneration given Mary by both Roman Catholics and Orthodox as something distracting from the latreia due to God alone. Some attribute widespread Marian devotion to a desire originating from pagan influence to have a female presence in the human experience of God. Orthodox and Catholics would answer that every person, man or woman, has the ability to believe in and come to know God, and since God the Logos, the Word, came into the world as the incarnate Son of Man, it is only natural that we seek to know Him through His mother.

Marian devotion in Orthodoxy is entirely Christocentric, revolving around and relating entirely to her role as Jesus’ mother. Because Mary is the Father’s chosen instrument of bringing His Son into the world, as she states in the Magnificat when she exclaims, “He has regarded the low estate of His handmaiden, from henceforth all generations shall call me Blessed”, we believe it is improper not to honor her. Some Catholics and Orthodox condemn as oversimplification and reductionist the tendencies among Protestant theologians and ministers to omit almost any mention of her. Aside from the reference to her in the Creed, she is overwhelmingly “toned down” by most Protestants (excluding High Church Anglicans) who are uncomfortable with her importance in earlier centuries of Christian theological development, and are skeptical of the attention that Christians of the earlier Church traditions pay her.

As with Roman Catholics, Orthodox refer to Mary as the Blessed Virgin, the Mother of God, and often ascribe to her the honorific “Queen” or “Lady”, depending on the translation, as she sits beside God the Father and her Son in heaven. One universal Orthodox title for Mary that does not usually appear in the West is the Greek term Theotokos, (lit. “Bearer of God”.) Another Greek honorific is Panagia, the “All-Holy” one whom the Father chose to carry His Son into the world, who “without corruption gave birth to God the Word”, without the pain and physical changes that alter all other women’s bodies during and after childbirth. Having been raised in the Roman Catholic Church, I can attest that devotion to Mary in Orthodoxy is as beautiful and just as much part of the liturgy as it is Roman Catholicism, if not more so.

While the Orthodox do not use the “Hail Mary” in the Liturgy per se (a more correct translation of the Greek ‘Chaire’ is “Rejoice”, rather than ‘Hail’) at the end of Vespers during an All-Night Vigil the choir will sing, in English “Rejoice O Virgin Theotokos” which is of almost identical wording to the Western Hail Mary.

Every Sunday Liturgy following the conclusion of the anaphora, the clergy and people chant the millennia-old Axion Estin (English: “It is truly meet”) which is similar in wording to the Magnificat sung by the choir and people at most All-Night Vigils. The Magnificat (from the Latin “I magnify”) is one of the most beautiful and compelling parts of our worship. In the majestic chanting of the choir the people and clergy’s voices join together to intone the very words that Mary exclaimed at her Annunciation. Throughout all Eastern Orthodox services, there is never instrumental accompaniment, since Orthodox hold the human voice to be the most pleasing sound to the God who created it.

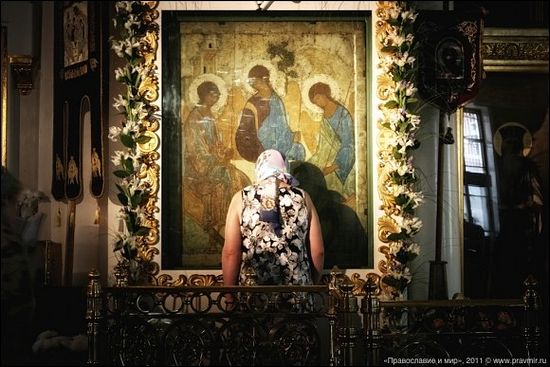

At the Magnificat, many worshipers are visibly moved—as St. Silouan tells us, tears in prayer are an expression of the heart’s desire to know God. Its beauty alone was something that drew me to attend the Saturday evening vigils at St. Nicholas. Every Orthodox church I have attended always offers a beautifully unique composition of the Magnificat, but the style at St Nicholas remains the one most touching to me. The celebrating clergyman comes out from the altar, turns to face the icon of the Blessed Virgin on the iconostasis, which he censes as he cries

The Theotokos and the Mother of the Light, let us magnify in song!

and then, as the choir begins the canticle, he processes around the church, censing all the worshipers as well as the icons of the saints. This is a reminder that the Church sings to the Lord in the presence of all the saints and the angels, who are present invisibly among us as Psalm 137 reminds us. The priest censes the people because Christ, truly God and truly man, bridged the “sacred distance” between heaven and earth, uniting the human and the divine natures in His single personage. Several times during each vigil the presiding clergyman, whether priest or bishop, census us as a salutation to the presence of God in each one of us, and so, when we honor Mary, we remember that it is through her, a person as human as any of us, yet who chose to never sin, that God the Word took on human form and lived among us as Jesus the Christ.