Bishop Kallistos correctly observes that,

“The Orthodox Church is not as much given to making formal dogmatic definitions as is the Roman Catholic Church.”

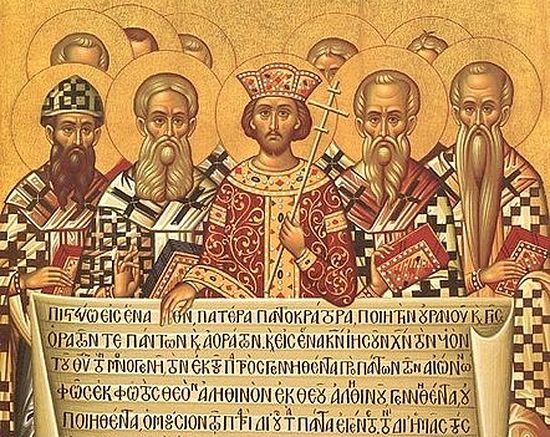

Yet there are certain elements of the Orthodox faith that have come into the Orthodox Tradition in past centuries and stayed there. One of these “unmistakable inner convictions” of the Church is the refutation of the Filioque clause, which played a defining role in the eventual Schism between East and West. The Filioque (Latin: “and the Son”) was first formally introduced in the West at the Third Council of Toledo in 589. This was a localized, non-ecumenical council in Spain convened by King Reccared and attended only by Spanish clergy, at which Arian bishops and clergy recanted their heretical views.

The insertion of the Filioque, which, pointedly, only gradually entered into use in the West, violates the Orthodox spirit and approach toward the inner Tradition that,

“Is preserved above all in the Church’s worship.”

No Ecumenical Council ever authorized its introduction in the Creed, nor, from a Roman Catholic perspective, did a pope ever pronounce it as infallible doctrine. Since Orthodox believe in the principle that, “Our faith is expressed in our prayer”, then the degree to which the West’s arbitrary insertion of the Filioque in the Creed offends the inner Tradition of the Church is a very high one. Even St. Augustine, one of the principal Latin Church Fathers credited with expressing the concept of Double Procession (that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son), repeatedly clarified his understanding of the Filioque with the ending tanquam ab uno principio—“as from one principle.” Thus, even to Augustine, the Holy Spirit’s procession rests on the centrality of the Father as this directing “principle” or originator within the Trinitarian framework, since any principle regarding the Trinity must have the Father as its directing head since the Father alone is unbegotten.

The Orthodox have been in many ways willing to compromise, or at least tolerate the idea that the Spirit proceeds “from the Father through the Son”, by virtue of Our Lord saying in John 15:26 that, “When the Comforter has come, whom I will send to you from the Father—the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father—He will bear witness to Me.” Jesus tells us that He “sends” the Spirit, but He states unequivocally that the Spirit proceeds from the Father alone. This is a question of the language our Lord used—he did not say, “the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father and I,” but, “proceeds from the Father” alone. In the past few years before I was receive into the Orthodox Church, whenever I attended Catholic Mass, I would either omit the Filioque or say “through the Son”, but for a considerable time the West’s logic for including the Filioque has defied my understanding.

The manner in which it was devised and declared (in a local Spanish council at Toledo with neither Ecumenical authority nor papal recognition), and the anti-conciliar manner in which it was implemented in the West violate the principle of “inner Tradition” of universally maintaining the Church’s time-honored traditions without alteration. Popes recognized the danger the Filioque posed and several condemned its gradual adoption into popular use in the West. Pope John VIII endorsed the decision of the Eighth Ecumenical Council of 879-880 at Constantinople, which reiterated the earlier 431 Third Ecumenical Council’s prohibition and anathematization of any alteration of the original wording of the Creed at Ephesus. Historian Dr. Margaret Trenchard-Smith of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles observes in her essay, “East and West: Cultural Dissonance and the ‘Great Schism of 1054’,” that Rome resisted the Filioque’s insertion into the Nicene Creed for several centuries after its first official declaration at Toledo in the sixth century.

Having promoted it at the Synods of Frankfurt (794) and Friuli (796), Charlemagne himself tried to insist on the inclusion of the Filioque in the Creed as normative practice in Rome in 809. However, Pope Leo III—the Pope who had made Charlemagne emperor—resisted the interpolation, as it would be “A mistake to depart from the version of the Creed that had been universally accepted by Christendom.” To impress upon contemporaries his point and to preserve it for posterity, the Pope had the original Latin and Greek versions of the Creed inscribed upon silver plaques placed within Saint Peter’s.

That Leo III, the very pontiff who crowned Charlemagne as Imperator Romanorum in St. Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Day in 800, refused the emperor’s desire to normalize the Filioque’s use at Masses in Rome speaks to the level to which the Pope saw himself as the defender of orthodox Christianity, the faith Rome then shared with the East. That he deliberately placed two silver plaques with the unaltered Creed in the central and most visited shrine in Rome, the site of St Peter’s execution and his tomb, demonstrates his rejection of the Filioque as a doctrine for the universal Church to espouse. One Catholic apologist with whom I have often talked argues that Pope Leo did this only to appease the Byzantines, who opposed Charlemagne’s campaign to normalize the Filioque in the West. His argument ignores the historical reality that in the very act of crowning Charlemagne Emperor of the Romans, the Pope had already offended and strained relations with the East.

The Byzantines had preserved their imperial succession of Eastern Roman emperors at Constantinople in the centuries after a Gothic king compelled the teenage Romulus Augustulus, the last Emperor in the West, to abdicate in 476. Ever since Constantine I moved the imperial capital to the Greek-speaking port of Byzantion in 330, renaming it, “New Rome”, the city’s inhabitants referred to themselves as “Romans”. Leo’s crowning of another emperor to rival one in Byzantium outraged many in the East. In 800, when he crowned the Frankish king, an emperor reigned in Constantine’s city, but Leo considered the imperial throne vacant because its occupant was a woman, Irene of Athens.

Trenchard-Smith observes in her essay’s endnotes (#42) that in fact Pope Leo sympathized with the Double Procession theory, which he put forth in his treatise Symbolum orthodoxae fidei Leonis papae. Ironically, it was in this work that Leo—who clearly from his title saw himself as the defender of the Orthodox faith—expressed his own belief in the Filioque, yet ecclesiastical scholars and theologians most remember him for erecting the two silver tablets in defiance of the same belief. We can deduce Pope Leo’s intentions on the Filioque through not only this public gesture against its introduction in Rome, but also from his refusal to permit the Filioque to be used when he publicly celebrated the Mass in Peter’s See during his lifetime. Most telling about the papacy’s attitude to the Filioque is that, as Trenchard-Smith observes,

Rome first used the Filioque in 1014 at the coronation of German Emperor Henry II.

The Roman rite in the Eternal City did not allow the clause until almost five centuries after it was first formally introduced into the West at Toledo. We have solid evidence that several Roman popes opposed the Filioque, but none that the clause was ever used in any Mass in Rome before 1014.

Implicitly tied to the Filioque controversy is what Orthodox theologians have found to be the West’s “tendency to subordinate and neglect the Spirit.”

The Catholic assertion that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both Father and Son suggests that the Spirit is fully dependent on both, and therefore a lesser or weaker part of the Trinity of God. If the Holy Spirit proceeds from both Father and Son, then the Spirit must proceed from something impersonal rather than Personal, since He would not be proceeding from one Person of the Trinity, the Father alone or the Son alone, but the divine substance or energy of the two Persons, which they have in common. This confuses the personal nature of the three hypostases of the Trinity.

Catholics and Orthodox share the belief that the Son was begotten of the Father “before all ages”, and we both believe that God the Holy Spirit and God the Word, the Logos who eventually became incarnate as Christ, created the world with God the Father, as Genesis 1:26 tells us God said “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” This presents a challenge to the Western understanding of the Trinity.

When do Catholics and Trinitarian Protestants (who continue to include the Filioque) believe the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father and the Son? They cannot say at Pentecost, for that is when Christ sent the Holy Spirit, already having proceeded from the Father, into the world. In the Creed, Orthodox and Catholics alike profess our belief that the Holy Spirit “spoke by the prophets” of the Old Testament, and Trinitarians will say the Spirit proceeded eternally or from time immeasurable, but it is theologically impossible for the Holy Spirit to have proceeded from the Father and the Son anytime before the Son’s Incarnation. Before His Incarnation of the Virgin Mary, He was not yet the God-Man, fully human and fully divine, but the begotten Son and impersonal Logos. Do you see how the Filioque clause confuses and dilutes the Holy Spirit, the third Person of the Holy Trinity?

Catholics traditionally have used three scriptural passages to explain their belief in the Holy Spirit’s procession from the Father and the Son in which the Spirit is respectively called the Spirit of Christ (Romans 8:9), the Spirit of the Son (Galatians 4:6), and the Spirit of Jesus Christ (Philippians 1:19).

The Orthodox understanding of these descriptions of the Holy Spirit is that because Christ is God Incarnate, the Spirit was of course present in Him and sent by Him into the world at Pentecost. However, these scriptural references to the Spirit relating to the Son do not address how the Spirit came to proceed from Father and Son in Western understanding, but simply that Christ, the Son of God, had the Holy Spirit’s grace and power because He is fully God. The Greek words which correspond to the Latin ‘procedere/procedit’ (to proceed/proceeds’) do not appear in any of these passages in question, and nowhere in Scripture do we have any examples where it is written that the Holy Spirit proceeds from Father and the Son. We do however have Christ’s words in John 15:26 that the Spirit

“Proceeds from the Father.”

The online Catholic Encyclopedia page on the Holy Spirit gives credence to the orthodox “Father through the Son” position, citing that,

The Greek formula ek tou patros dia tou ouiou [Greek: from the Father through the Son] expresses directly the order according to which the Father and the Son are the principle of the Holy Ghost…

Yet the Encyclopedia errs in reflecting the Catholic belief that this formula somehow “implies their equality as principle”, that the Father and Son are equally the source of the Spirit which must, therefore, proceed from both. The Encyclopedia continues,

As the Son Himself proceeds from the Father, it is from the Father that He receives, with everything else, the virtue that makes Him the principle of the Holy Ghost. Thus, the Father alone is principium absque principio, aitia anarchos prokatarktike, and, comparatively, the Son is an intermediate principle.

The Catholic clarification that, “the Son from the Father receives the virtue that makes Him the principle of the Holy Ghost” is unnecessary in the Orthodox view. Since we hold that the Spirit proceeds only from the Father, we do not need to explain how the Son receives “the virtue” that makes the Spirit also proceed from Him—we do not have this problem since we hold to the original wording of the Creed. Furthermore, Catholic belief that “the Son is an intermediate” connecting or standing between the Father and the Holy Spirit is another example of Orthodox apprehensions that the Filioque confuses the relationship between the Persons of the Holy Trinity.

Orthodox theology, in contrast, has a more internally balanced and unified view of the Trinity: everything the Church holds God to be can be attributed to one Person of the Godhead, or to the three Persons in triunity. The Father, the Logos, and the Spirit were present at the creation of the world and before all sense of time. God the Father is the “maker . . . of all things visible and invisible,” God the Son is “begotten of the Father before all ages” as the Logos, and God the Spirit “proceeds from the Father”—the Father is the source of both Son and Spirit, who proceed from Him eternally. Because the Orthodox theology of the Person of the Holy Spirit is unconfused and does not require the philosophical extrapolation and clarification, which the Filioque does, Orthodox worship and spirituality has maintained a close connection to third Person of the Trinity, “the Paraclete, the Comforter, the Spirit of Truth.” We invoke the protection of the Spirit in our personal morning devotions and evening prayer before we sleep, and constantly during the Liturgy.

After reading several of his writings, I have come to love and greatly esteem St. Seraphim of Sarov, and his observation that,

“The true aim of the Christian life is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God.”

With this incredibly challenging and beautiful aspiration, the true Orthodox life becomes one of an ever-occurring process of theosis, or deification, where we strive to become one with the energy of God in all ways, constantly endeavoring to let ourselves be filled with the Holy Spirit. This call to begin a long process of aspiration to godliness, to become one with God as “partakers of the divine nature” through the light and inspiration of the Holy Spirit, as Saint Peter tells us, is such a beautiful thing. It is something that strikes me as the perfect embodiment of Christianity—striving to become one with God. St. Athanasius of Alexandria reminds us in On the Incarnation that,

“The Son of God became man that we might become god.”

This is not just a passable offer from anyone—this is the very reason for the Incarnation of the Logos, the Word—why the Father sent His Son into the world to dwell among us!

Since I first began my studies of Orthodoxy, I have noticed that Eastern theology is imbued with a kind of awareness of the Holy Spirit’s presence and importance that I had only once briefly experienced in any Western church. When my class was preparing for confirmation at St James Roman Catholic parish in high school, our pastor Father Robert Smith (we called him Father Bob), a very kind man, enjoined us to sing with him a vernacular hymn, “Send Us Your Spirit” by David Haas, the refrain of which is,

“Come Lord Jesus, send us your spirit, renew the face of the earth!”

This struck me as being so beautiful, and so different from what I was used to in church—confirmation was the one time, as far as I remember, that the Church had ever really focused on the Holy Spirit outside of Pentecost. When I heard my pastor singing this beautiful supplication to the Spirit, it seemed to me such a perfect calling toward all that I sought to be as a Christian: loving God, opening up oneself to the work of the Spirit, serving and loving others, and seeing God alive in humanity. Yet I never experienced any awakening or transformation like it again while I was a Catholic.