Both Roman Catholics and Orthodox would agree with St. Ignatius in his letter to the Smyrnaeans (viii, 2) when he observes that “where Christ is, there is the Catholic Church.” Similarly, Orthodox and Catholic do not disagree that “the Church is the extension of the Incarnation, the place where the Incarnation perpetuates itself.”

Certainly both Catholic and Orthodox would agree with St. Maximus the Confessor (580-662) in his observations in his seventh century Mystagogy that “the holy church of God … is a figure and image of the world, which is comprised of visible and invisible things … The Church is essentially one.”

Where the two traditions differ is in their conception of how this oneness or “catholicity” is expressed and in what manner the Church should guard the faith.

For Rome the unifying principle in the Church [in other words, what makes it truly one, universal, or catholic] is the Pope whose jurisdiction extends over the whole body, whereas Orthodox do not believe any bishop to be endowed with universal jurisdiction.

The heart of this debate rests in the Churches’ differing understandings, textually and historically, of Matthew 16:18 when Christ says to Simon Peter, also called Cephas: And I say to you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.

When I was younger, I would have assumed, as I had been taught, that this passage clearly endorses the papacy as the reservoir of universal Christian jurisdiction on earth. Now that seems to be a real distortion and I approach the text with a different understanding. It seems that Christ is choosing Peter, as an especially beloved and dedicated follower, to fulfill a special pastoral role in the Christian community after His death. There is no example from Holy Scripture in which the apostles understand Peter to have infallibility or supreme authority over them after Christ’s death and Resurrection, as the Roman Catholic Church has claimed for centuries. In fact, in Galatians 2:11, St. Paul writes that when Peter was come to Antioch, I withstood him to his face, because he was to be blamed.

The Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible translates Peter here as “Cephas,” but this is an equivalent Greek name for Peter. This passage is a public assertion by St. Paul of his equal statute to St. Peter in apostolic authority and dignity, and far from suggesting that Peter was the infallible Prince of the Apostles, this passage shows that he was capable of making a mistake, an error that another apostle corrected.

There is no reason to think that just because Peter was given a special commendation by Christ that any sort of universal jurisdiction applies to his successors as bishops in Rome, some of whom were soldier-warriors, princes, and even murderers. Nowhere in the Bible is there any statement that Peter’s successors should have infallible power or supreme apostolic authority. A Catholic apologist with whom I have talked points to Matthew 16:18-19 as the justification for Rome’s claims. I then would point to John 20:23, where Christ speaks to all the apostles, not only Peter: Whosesoever sins you remit, they are remitted to them; and whosesoever sins you retain, they are retained.

“You” here in the Greek appears in the plural, confirming that Christ was speaking to the apostles together. If Peter was considered to be the prince of the apostles, their supreme leader and the chief shepherd of the Church after Christ’s death, Resurrection and Ascension, why did Christ give to all the Apostles equal authority to remit sins?

As I read over the text of Mark 16:18, it seems to me that Christ is foretelling the struggles that the Church would face in its infancy against pagan Roman persecution and endless heresies. He seems to be entrusting Peter with a certain brotherly charge toward the other apostles in the loving way that other first bishops were the spiritual and pastoral cores, or hearts, for the local faithful as the leaders of the first churches. This is only my humble interpretation.

As a result of diverging interpretations of this scriptural passage, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches have approached the question of communion of belief and matters of jurisdictional authority in different ways. Where the Roman Catholic Church is “often seen too much in terms of earthly power and organization” due to its more administrative, executive understanding of the papacy, Roman Catholics will, in turn, often see the “more spiritual and mystical doctrine of the Church held by Orthodoxy as vague, incoherent, and incomplete.”

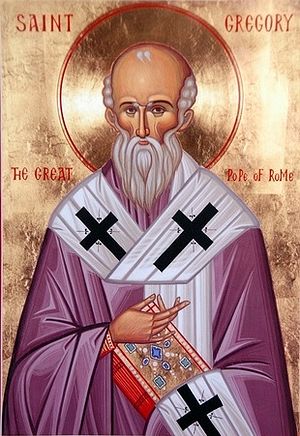

While traditionalist Catholics tend to believe that their Church has always defended the Papacy’s powers of supreme and universal jurisdiction, there is strong evidence to suggest that this view gradually evolved in the West. One pope, venerated as a saint by both Catholics and Orthodox, Pope St. Gregory the Great (r. 590-604), famously opposed Patriarch John of Constantinople’s desire to add the term “Ecumenical” to his title, writing to the patriarch that

Whoever calls himself the universal bishop, or desires this title, is, by his pride, the precursor of Antichrist, because he thus attempts to raise himself above the others. The error into which he falls springs from pride equal to that of Antichrist; for as that Wicked One wished to be regarded as exalted above other men, like a god, so likewise whoever would be called sole bishop exalteth himself above others.

Pope Gregory’s unequivocal condemnation of any primate calling himself “universal” or sole bishop might shock most Catholics who have never read it, since the Catholic Church has long attempted to convince its faithful that popes always professed the claim to universal authority and immediate jurisdiction over all other Christian sees. Yet St. Gregory clarifies that this is anything but the case. He points out to Patriarch John that even when the 451 Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon offered the bishop of Rome the honorary title of ‘universal’ bishop, the reigning pope refused to accept it:

You know it, my brother; hath not the venerable Council of Chalcedon conferred the honorary title of ‘universal’ upon the bishops of this Apostolic See [Rome], whereof I am, by God’s will, the servant? And yet none of us hath permitted this title to be given to him; none hath assumed this bold title, lest by assuming a special distinction in the dignity of the episcopate, we should seem to refuse it to all the brethren. [Emphasis mine.]

This is the very antithesis of a pope claiming universal power and authority over all other Christian sees. Pope St. Gregory refers to his fellow bishops as “brethren” and cautions against any bishop “assuming a special distinction in the dignity of the episcopate.” He not only reiterates that since his predecessors as Roman popes, first in honor among the five apostolic sees or patriarchates, declined the honorary title “universal,” all other patriarchs ought to avoid using the term, but he specifies that even when the fathers at Chalcedon offered the popes this title, they understood it primarily as an honor of distinction, rather than a recognition of the Papacy’s unique power. St. Gregory clearly feared that this honorific title and similar ones offered to previous Roman popes could lead to an improper and heterodox elevation of one of the patriarchates above the others. Even the title “pope,” meaning “father,” was first applied not to the bishop of Rome, but to the Patriarch of Alexandria. To this day the patriarch of Alexandria is still addressed by this ancient title preceding the Roman one.

How does this early pope’s view of universal jurisdiction compare to the Catholic Church’s teachings on papal authority today? In Christus Dominus, the Decree Concerning the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church promulgated by Pope Paul VI on October 28, 1965 during the Second Vatican Council, Section II of the Preface states:

In this Church of Christ the Roman pontiff, as the successor of Peter, to whom Christ entrusted the feeding of His sheep and lambs, enjoys supreme, full, immediate and universal authority over the care of souls by divine institution.

This is understood as a “primacy of ordinary power over all churches.”

Section II of Christus Dominus, titled “Bishops and the Apostolic See,” describes the Pope as “exercising supreme, full, and immediate power in the universal Church.”

These words differ markedly from those of Pope St. Gregory some thirteen centuries earlier who was so cautious not to take to himself an honorific title he believed would elevate the Papacy far above the other sees.

The Roman Catholic Church today still asserts the Papacy’s universal and immediate jurisdiction over all Christians. Part I, Section 2, Chapter 3, Article 9, Paragraph 4, Section I of the 1997 Second Edition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church states that

The Pope, Bishop of Rome and Peter’s successor “is the perpetual and visible source and foundation of the unity both of the bishops and of the whole company of the faithful.” “For the Roman Pontiff, by reason of his office as Vicar of Christ, and as pastor of the entire Church has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered.

This is the very antithesis of the episcopal collegiate conciliarity which is a key part of the ancient Tradition which administered and held together the sees of the early Church. As these words show, the Catholic Church today teaches that the Bishop of Rome, not Christ, is the “perpetual source and foundation of the unity” of the Church itself, both for the bishops and “the whole company of the faithful.” Unsurprisingly, those Catholics who believe such a legalistically-defined and power-based concept of universal papal jurisdiction and power over the Church are likely to ask, “If Orthodox reject papal claims to universal jurisdiction, what could possibly keep their Church together?”

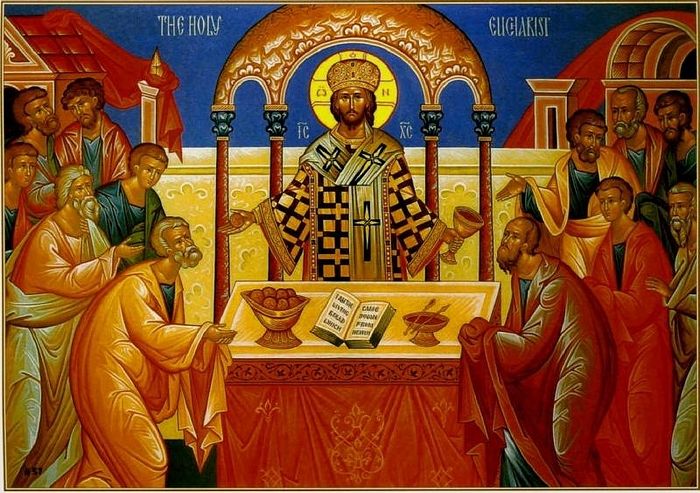

The Orthodox answer is one of the most beautiful examples of our faith. The Church is united not by one man but by

the act of communion in the sacraments. The Orthodox theology of the Church is above all else a theology of communion. Each local Church is constituted by the congregation of the faithful, gathered round their bishop and celebrating the Eucharist; the Church universal is constituted by the communion of the heads of the local Churches, the bishops, with one another.

Rather than a Pope externally maintaining the unity of the Church through his “supreme and universal power” over all believers, the Orthodox emphasize the Church’s catholicity, its wholeness, at a local level throughout the world. Wherever you have “the faithful gathered round their bishop celebrating the Eucharist” you have the Orthodox faith, and the Church’s pastors, its bishops, “in communion with one another” exercise local responsibility for maintaining it alongside the faithful laity. Thus, to the Orthodox believer, one’s bishop is not the distant administrator that he commonly is to the vast majority of Roman Catholics, but a pastor, a spiritual advisor, even, in small enough dioceses, a beloved family friend. Because dioceses are smaller in size, many Orthodox bishops are able to fulfill the role most commonly given to the parish pastor in Catholicism.

The internal strength, continuity, and timelessness of the Orthodox Church is so because, unlike in Roman Catholicism where the Church’s liturgical life, spiritual health, and overall dogma depend heavily on arbitrary inclination, and can, by canon law and practice, be changed at will by a Supreme Pontiff who maintains unity from without, in Orthodoxy “unity is created from within by the celebration of the Eucharist.”

We do not see the need (or the orthodoxy) in vesting one single see, one prelate as “Supreme Pontiff” to maintain the Church from without. Indeed, if one examines the state of the Catholic Church today, one sees liturgical chaos in more liberal parishes and often a reactionary (rather than an organic) conservatism in traditionalist ones which has produced sedevacantists[1], certain fringe members of the SSPX, etc. Where is the unity of faith Rome always championed?

Sadly, many Catholics are aware that the historic unity of their faith is gone. Traditional Catholics will be the first to admit that the Roman Church today is far less orthodox than it was in 1054 or 1439. Examine its worship: there is no longer unity in the inner liturgical life of the Church. In one parish you have traditionalists clinging to the Latin Tridentine Mass, the current Extraordinary Form of the Roman rite, while in most you have the much more informal services of the Novus Ordo style, spoken (no longer sung) in the vernacular, with mostly Protestant or post-Vatican II hymns with diverse instrumental accompaniment including trumpets and string instruments.

While Rome (and the Protestant churches which evolved out of and in reaction to the early modern papacy) defines the Church in an invariably legalistic and rational framework, harking back to Augustinian juridical theory and Scholasticism, Orthodoxy sees the Church as the living and mystically united Body of Christ carried on through the treasured deposit of a living Holy Tradition. Fidelity to this core has enabled her to defend the faith from within the context of a dynamic fidelity to this Tradition, which means that we value adherence to the faith of the early Church and the maintenance of collegiate conciliarity as the framework for Church unity. We believe this is the surest way to carry this living Faith into modernity. While we maintain koinonia[2] from within, and see the Catholic Church as the faithful everywhere in faithful communion with their bishops, including those living among us and those faithfully departed who sleep in Christ, we are internally accountable for defending and living the Faith—bishops to each other, priests to bishops, laypersons to father confessors and spiritual mothers, and so on. This is the very antithesis of the top-down hyper-centralized Catholic administrative approach to maintaining communion which sets one man, the Pope, as the source and symbol of the faith’s unity.

In his April 10, 2009 Ancient Faith Radio podcast interview with Fr. Andrew Jarmus, the director of OCA Communications, His Beatitude Metropolitan Jonah aptly described the less-coercive nature of Orthodoxy when he said that “in the Church there is absolutely no room for obedience as power. There is no room for coercion in the Church, there’s no room for subjection in the Church, there’s no room for submission, other than to the will of God Himself.” There has never been anything corresponding to the Inquisition in the Christian East, and punishment for heresy during the Byzantine and Russian empires generally involved excommunication and a fine, sometimes exile, and only rarely incarceration.

Having been raised in the Catholic faith since my birth, I can attest that the Orthodox Tradition is not only very much complete, but that the Roman Catholic Church’s more legalistic focus, manifested, for example, in its scholastic declarations on the process of transubstantiation, has major limitations. The view of the Eucharist as a “Divine Mystery” does not hold up to logical Aristotelian formulae, so in the thirteenth century influenced by Thomistic thought the Roman Church dogmatized “transubstantiation.” This is the philosophical formula that the elements in the consecration are materially changed to Flesh and Blood and only the “accidentals” of bread and wine, that is, their outward appearance, remain visible.

From the Orthodox perspective, we do not see the purpose in attempting to rationalize what the faithful have from time immemorial received reverently as a divine mystery. In the Divine Liturgy we affirm that we believe the bread and wine are changed in a divine Mystery at the epiclesis “by the power of the Holy Spirit” into “the most precious Body and Blood of Christ.” In the opening words of our communion prayer, we say:

I believe, O Lord, and I confess that thou art truly the Christ, the Son of the living God, who came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am first. And I believe that this is truly thine own most pure Body, and that this is truly thine own precious Blood.

We do not see the need to postulate, as Thomas Aquinas did, that in the changing of the bread and wine into Body and Blood, the substance is materially altered—hence the Latin term transsubstantiatio. This seems to philosophize and rationalize what the Church has understood for centuries to be a holy, awe-inspiring, and incomprehensible Mystery. Likewise, the Orthodox Church has never dogmatized a view on purgatory, but has always taught that souls require some form of purification if they are to enter into the presence of God in the next world (Revelation 21:27). Rome’s dogmatization of purgatory is a later development foreign to the beliefs of the early Christians.

Because I was always told that transubstantiation is the exact moment in the Mass when, after genuflecting before the Holy Gifts, the priest by the Holy Spirit changes the bread and wine into Christ’s Body and Blood, my experience of the Mystery that occurs at the epiclesis was never so much an incomprehensible holy transformation as it was a kind of already-defined, almost scientifically precise thing, of whose essence and mystical power I was actually quite ignorant. The Orthodox emphasis on the change that takes place at the Eucharist by the Holy Spirit’s mysterious transformative power, or metousiosis, while not really differing theologically from the Catholic definition of transubstantiation, allows for the preservation of a strong degree of heightened anticipation, awareness, and sense of wonder among the laity at the consecration.

Rather than trying to rationalize and explain it as Thomas Aquinas and others did, we keep it as a holy Mystery. St. Germanus, aforementioned eighth century patriarch of Constantinople, gives the following detailed description of the significance of the symbols and movements during the epiclesis of the Eastern liturgy in his Ecclesiastical History and Mystical Contemplation. After declaring “to the God and Father the mysteries of Christ’s incarnation, His ineffable and glorious birth from the holy Virgin, His dwelling and life in the world ... His holy resurrection from the dead on the third day, His ascension into heaven ... His second and future glorious coming,” the priest then silently

expounds upon the unbegotten God, that is the Father, and on the womb which bore the Son before the morning star and before the ages, as it is written: “Out of the womb before the morning star have I begotten you” (Psalm 109:3). The priest asks God to accomplish and bring about the mystery of His son—that is, that the bread and wine be changed into the body and blood of Christ ... then the Holy Spirit, invisibly present by the good will and volition of the Father, demonstrates the divine operation, and, by the hand of the priest, testifies, completes, and changes the holy gifts which are set forth into the body and blood of Jesus Christ our Lord, Who says: “For their sake I sanctify myself, that they also may be sanctified (John 17:19), so that “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me and I in him” (John 6:56).

St. Germanus describes the epiclesis as a profoundly transcendent moment, but nevertheless a mystery of inexplicable power and grace, in which the clergy and the people together become

eye-witnesses of the mysteries of God, partakers of eternal life, and sharers of the divine nature ... the priest’s performing the divine mystery while bowing down manifests that he converses invisibly with the only God, for he sees divine illumination, he is made radiant by the brightness of the glory of the face of God.

This deeply mysterious understanding of the changing of the elements into the Body and Blood of Christ reflects Orthodoxy’s spiritual richness, manifested in the poetic beauty and transcendence of the wording of the Liturgy.