Although I have already written on the Liturgy extensively, I wish to leave you with some final observations. Metropolitan Kallistos observes that “the Orthodox peoples have poured their whole religious experience into the Holy Liturgy which expresses their faith. It is the Liturgy which has inspired their best poetry, art, and music.” This is true, as anyone with an art history background or possessing an ear for the works of Rachmaninov or Gregoriev can tell you.

Similarly, in his own reflections in his book The Orthodox Liturgy, Austin Oakley observes that the liturgy has always been one of the most integral aspects of Orthodox identity and faith, both personal and communal: “The normal lay worshipper, through familiarity from earliest childhood, is entirely at home in church, thoroughly conversant with the audible parts of the Holy Liturgy.” I have come to increasingly feel this way as I continue to participate in liturgies and vespers services. As a result of such a deep feeling of communion, ordinary Orthodox worshippers “take part with unconscious and unstudied ease in the action of the rite, to an extent only shared in by the hyper-devout and ecclesiastically-minded in the West.”

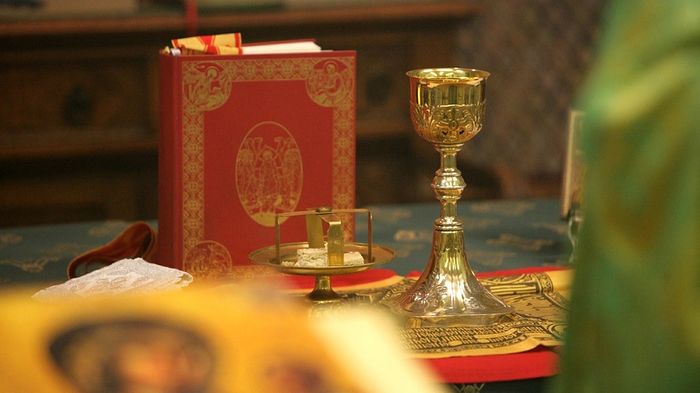

In the Liturgy one discovers the Inner Life of the Church, for it is in the Liturgy, beloved, treasured, and defended by Orthodox for centuries, that the faithful so clearly manifest their abiding devotion. The Liturgy, as something which has remained almost entirely unchanged for centuries, whose essential form dates to over sixteen hundred years ago, is, to me, one of the greatest gifts of Orthodoxy that I will receive when I am chrismated. In the Liturgy are found the best embodiments of the “living Tradition” to which the faithful cleave. Metropolitan Kallistos correctly, and with some sense of humor, observes that Orthodox are constantly talking about Tradition. Yet what does this word really mean? Is it a kind of reactionary, mechanical, static devotion to all things old? Such tradition, if that were Orthodoxy, could only be called empty.

Of course, the word has different significance for different people. Certain Orthodox parishes that are more ethnically-oriented (specific communities of Russians, Serbians, or Syrians, etc) may sometimes strike people unfamiliar with them as being more mechanical in nature, cleaving to specific ritual observance rather than a broad, more informed Tradition. If you are inclined after reading this to visit an Orthodox church, there is a small chance that you might step into one like this, where, if you don’t immediately venerate an icon, people might look at you as if asking, silently, “Why are you here?” Do not be afraid if this is the case; rest assured, most parishes are not like this, and such behavior is not in the spirit of Orthodoxy.

As Metropolitan Kallistos observes, the true Orthodox Tradition is one which is far from static: the life and light of the Church are vividly expressed in the Liturgy, a word which means “the work of the people.”

It is here that the life of the Church is most evident, the heart and soul of the Faith where the priest, representing Christ, and the faithful come together and worship before the invisible powers of heaven. Yet the life of the Church is also present in the day-to-day trials and interactions of parish communities. The Church is present whenever the local body gathers as an assembly to bring new members into the Orthodox fold in baptism and chrismation, whenever it celebrates the joining of a man and a woman in holy matrimony with high solemnity and radiant joy, or commemorates the passage of loved ones into the next world. The Church lives also in its centuries of accumulated teachings, which are replete with oceans of ink in wisdom: the writings of the Ante-Nicene and early Fathers, the lives of the saints, and above all, the Psalms, the “prayer book of the Church,” and the Holy Scriptures.

The Orthodox sense of obligation toward and honoring of Tradition is anything but empty or outdated; the exact perception of Church Tradition is something that differs in each person, with different practices from parish to parish manifesting in different cultural and linguistic traditions. Yet the faith remains the same everywhere. Metropolitan Kallistos reminds us that

Loyalty to Tradition, properly understood, is not something mechanical ... An Orthodox thinker must see Tradition from within, he must enter into its inner spirit. In order to live within Tradition, it is not enough simply to give intellectual assent to a system of doctrine, for Tradition is far more than a set of abstract propositions—it is a life, a personal encounter with Christ in the Holy Spirit.

This invitation to enter into the Tradition’s “inner spirit” is the shining beacon of Orthodoxy. Metropolitan Kallistos’ avowedly dynamic conception of the way of the Church, which he observes is inwardly changeless, is one in which individual believers’ approaches to this Tradition are “constantly assuming new forms, which supplement the old without superseding them.”

The Holy Spirit is constantly connected to this perpetually renewing sense of Tradition. Georges Florovsky refers to Tradition as no less than “the witness of the Spirit.” Therefore, it is an informed, contemplative reverence for the Church’s many traditions, all revealed together as part of its great Tradition, combined with spiritual openness and introspection, which is the key to developing a richer, more self-aware Christian life. Orthodox are seriously called to be witnesses to this “Tradition of the Spirit.”

I would be misleading you if I said that Orthodoxy does not involve and require a deep appreciation for and sense of devotion to its traditions. Yet it is worth one final time noting the words of the estimable Metropolitan Kallistos, who reminds us that “true Orthodox fidelity to the past must always be a creative fidelity.”

Loyalty to Tradition, properly understood, means accepting that Tradition is not only something “kept by the Church” exactly as it was some fifteen centuries ago. It is something that “lives in the Church, it is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church ... a living discovery of the Holy Spirit in the present.”

The challenge for each Orthodox person is to enter into the fullest possible awareness of how studying, honoring, and above all living this Tradition will bring them to a closer communion with God, a greater sense of self and a deeper understanding of human nature.

Bearing all this in mind as I prepare for chrismation, I am reminded of the opening words of the Magnificat:

My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my savior!

I use an exclamation point because when the Virgin received news that the Father had chosen her of all women to bring His Son into the world, she “exclaimed” rejoicing, for she was filled with overwhelming gladness. An indescribable gladness fills my heart and warms my soul as my chrismation approaches. In my own small way, and ever-conscious that I sin, while the Blessed Lady was without corruption, I rejoice to have found the Orthodox way. Mindful of the many preparations that lay ahead, I close with the familiar words of praise rendered by King David in the psalm which he taught to Solomon:

Blessed art thou, O Lord, teach me thy statutes …