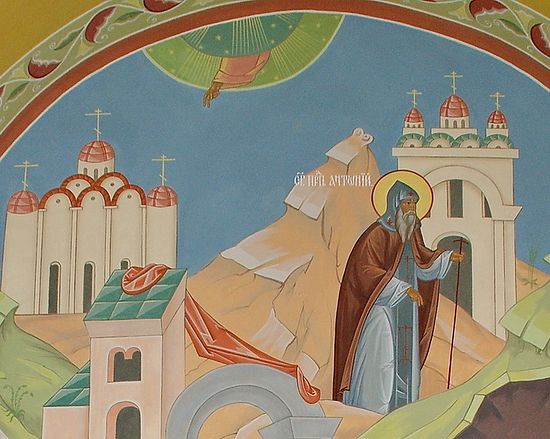

St. Anthony and Theodosius of the Kiev Caves. Artist: Saida Afonina

St. Anthony and Theodosius of the Kiev Caves. Artist: Saida Afonina

On July 10/23, the Orthodox Church commemorates Venerable Anthony of the Caves, the founder of the Kiev Caves Lavra. This ascetic holds a special place among ancient Russian saints and is traditionally revered as the “chief of all Russian monks” because the monastery he founded on the hills of Kiev served as a center and school of ancient Russian monasticism and enlightenment for all of Rus’, for many centuries.

However, despite the central significance of St. Anthony’s personality in the history of the Russian Church and Rus’, surviving information about him is quite scant and contradictory. There is particularly little information about the period of his stay on Mt. Athos.

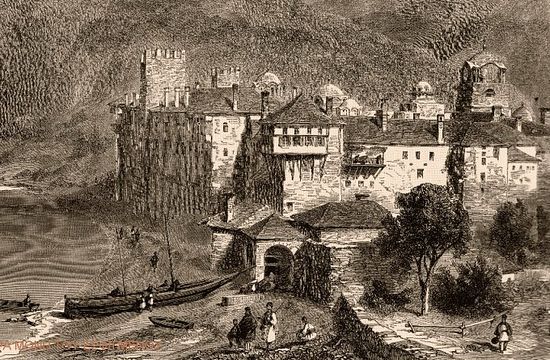

In recent times, popular literature fostered the idea that St. Anthony of the Caves was an ascetic in the Esphigmenou Monastery on Mt. Athos, evidenced by a small cave with a church built over it at the end of the nineteenth century dedicated to St. Anthony of Esphigmenou.

But did this cave really belong to Anthony of Kiev? And is St. Anthony of Esphigmenou truly identical to Venerable Anthony of the Caves? This question remains open, as no substantial evidence has been presented for the Esphigmenou hypothesis, which spread from the mid-nineteenth century.

In addition to the well-known cave of Anthony of Esphigmenou, there was another cave on Mt. Athos in the nineteenth century, also attributed to Venerable Anthony of the Caves, located near the Great Lavra of St. Athanasius. It is mentioned in the pilgrimage accounts of Hieromonk Hippolytus (Vyshensky) and others.

Most researchers believe this was an attempt by pious Russian pilgrims, who began to actively visit Mt. Athos in the nineteenth century, to independently find the place of the revered “chief of all Russian monks.” But while the Great Lavra refused to recognize the pilgrims’ identification of the cave within its bounds, the Esphigmenou Monastery deemed it possible and allowed Russian pilgrims to build a church over the cave in the name of St. Anthony of Esphigmenou.

It should be noted that the Esphigmenou hypothesis was sharply criticized by several prominent church historians and archaeologists shortly after its emergence in the nineteenth century. Among the skeptics were Bishop Porphyry (Uspensky), who worked extensively in the archives of the Athonite monasteries; Archimandrite Antonin (Kapustin), who studied the monasteries of Mt. Athos in 1859; Professor Eugene Golubinsky and others. Independently, they all concluded that the Esphigmenou biography and the cave presented by the Esphigmenou monks were not authentic and were “invented” on the eve of the visit of Grand Duke Constantine Konstantinovich Romanov to Mt. Athos in 1843 to attract the attention of distinguished Russian pilgrims to their monastery.

The Esphigmenou biography of Venerable Anthony, published during this period, originally suffered from significant chronological inaccuracies, raising questions about whether the Greek and Russian hagiographies spoke of the same saint. According to the Greek version, Venerable Anthony was a Greek by nationality and came to the monastery in 973, receiving his monastic tonsure in 975 from the abbot of the Esphigmenou Monastery, Theoctistus. However, Russian hagiographies unequivocally assert that Venerable Anthony of the Kiev Caves was not a Greek but a Russian, born in 983 in Lyubech in the Chernigov region. Thus, Greek Anthony of Esphigmenou cannot be identical to Anthony of the Caves, as the former came to Esphigmenou ten years before the latter was born.

It is more likely that Anthony of Esphigmenou did indeed exist and even labored in a known cave on the slope near the Esphigmenou Monastery. However, there are no grounds to identify him as Venerable Anthony of the Caves.

The mention that the Greek Anthony of Esphigmenou came to Athos in 973 and was tonsured two years later was likely borrowed from the Esphigmenou monastery’s martyrology, where the entry for the specified dates may indeed report the admission and tonsure of a monk named Anthony, of Greek origin.

Subsequently, the Esphigmenou Monastery repeatedly edited its biography of Venerable Anthony of Esphigmenou, trying to align the inaccuracies with Russian sources. New “chronological details” arose, which, along with existing accumulated errors and versions, significantly complicate the scientific dating of the biography. For instance, one of the latest revisions introduces a new date—1035—when the saint was supposedly tonsured into the small schema by Abbot Theoctistus II at the age of fiftey-two. As can be seen, the age of Venerable Anthony was already adjusted to align with Russian sources.

Referring to the emerging legend in Esphigmenou, in 1895, the abbot of the monastery, Archimandrite Luke Agiographos, petitioned the Kiev spiritual consistory to establish a dependency of the Esphigmenou Monastery in Kiev with a chapel in honor of Sts. Anthony, Athanasius, and Gregory. However, the spiritual consistory, chaired by church historian Archpriest Peter Lebedintsev, did not make a favorable decision on June 16, 1895, due to a lack of convincing evidence. Father Peter Lebedintsev wrote in his review that “there is no record or tradition in the chronicles and the Patericon of the Caves about the stay and tonsure of Anthony of the Caves in the Esphigmenou Monastery on Athos.” The final decision was made by the Holy Synod on October 12, 1895, addressed to the Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia Ioannikiy, where the petition of the abbot of the Esphigmenou Monastery was declined based on the above reasons.

It is important to note that besides the relatively late legends about the existence of the caves of Venerable Anthony of the Caves near the Great Lavra of St. Athanasius and the Esphigmenou Monastery, there is an older and more credible tradition on Athos that the future father of Russian monasticism initially labored in asceticism not in a Greek, but in a Russian monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos (“Panagia Ksilurgu,” or “Woodworker”).

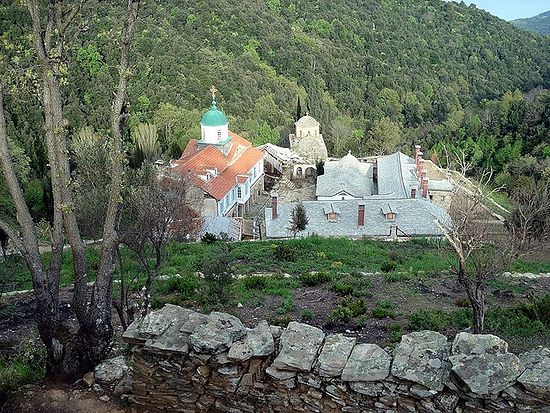

Ksilurgu Skete. Photo: Sergei Shmel

Ksilurgu Skete. Photo: Sergei Shmel

Archivist and librarian of the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery on Athos, Schemamonk Matthew (Olshansky), after the “Esphigmenou hypothesis” was first publicized, expressed bewilderment on behalf of the Russian monastery and its elders, Hieroschemamonk Jerome (Solomentsov) and Schema-Archimandrite Macarius (Sushkin). For among the Russian monks on Mt. Athos, there has long been a popular tradition that Venerable Anthony of the Caves labored specifically in the ancient Russian monastery of Ksilurgu. In his “Guide to the Holy Mt. Athos,” published in 1895, Father Matthew mentions the tradition that St. Anthony labored in this monastery. And when new revisions of the Esphigmenou biography appeared, and the Greek version began to gradually penetrate the consciousness of the Russian public, Fr. Matthew sharply commented on this, particularly the interpretation involving the name of the abbot who tonsured St. Anthony. The Greeks still called the abbot Theoctistus, but this time “the Second.” This name was taken from a genuinely existing mutual act of the Esphigmenou and Ksilurgu monasteries from 1030, which mentioned the names of their abbots—Theoctistus and Theodulus. Indignant at the blatant manipulation of names, Fr. Matthew ironically exclaimed, “So why can’t the elder who tonsured Venerable Anthony be the Russian abbot Theodulus mentioned in the same act?”

It should be noted that Ksilurgu (Greek ξυλουργός—carpenter or woodworker) is the oldest Russian Orthodox monastery not only on Mt. Athos but in the whole world, founded soon after the Baptism of Rus. The very name, “Woodworker”, testifies to its Russian roots, for only the Rus’ initially built their dwellings, churches, and monasteries out of wood, while the Greeks used stone.

Ksilurgu Skete. Photo: Sergei Shmel

Ksilurgu Skete. Photo: Sergei Shmel

According to tradition, the ancient Russian monastery of Ksilurgu was founded through the efforts of St. Vladimir, Equal-to-the-Apostles, Prince of Kiev († 1015), and his wife, the Byzantine Princess Anna († 1012) soon after the adoption of Christianity in Rus. From the Tale of Bygone Years, we learn that after the baptism, the Grand Prince Vladimir sent an emissary to Jerusalem and Constantinople. Soon near Jerusalem and on Mt. Athos, two monasteries appeared with the same name: the Russian Monastery of the Theotokos. The Russian monastery in the Holy City ceased to exist three centuries later, but the monastery on Mt. Athos still exists today.

The catholicon of the Russian Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” on Athos is dedicated to the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos. It is known that the monastery founded by Venerable Anthony upon his return from Athos, the Kiev Caves Monastery, was symbolically dedicated, like its cathedral church, to the Dormition of the Mother of God.

The foundation of the monastery on the Kiev hills in honor of the Dormition and the construction of the majestic Dormition Cathedral, carried out with the blessing of St. Anthony, were seemingly symbolic projections of their prototype—the Holy Dormition Russian monastery “Ksilurgu” and its catholican on Mt. Athos, where, according to tradition, the future abbot and “father of Russian monasticism” grew spiritually and took his monastic vows. Thus, Venerable Anthony attempted to transfer the idea of sacred space to the newly converted land of Kiev, creating, so to speak, a “Russian icon” of Holy Mt. Athos as the Habitation of the Theotokos in Rus’. It is not by chance that the Kiev Caves Monastery was called “the third Lot of the Theotokos”, and the “Russian Athos” from the very beginning of its formation. As the Orthodox theologian Archpriest Lev Lebedev wrote, “According to Orthodox teaching, an image by means of its symbolic similarity to the prototype becomes endowed with the same grace-filled energies as the prototype, mystically but truly contains the presence of the prototype. This applies to architectural images as well. The energies of the prototype can also act within them... The development and embodiment of this concept in visible architectural images and the names of various places may be the most striking feature of the church-theological and popular consciousness of Rus’.”

It is no coincidence that in the Kiev Caves Patericon, following the Athonite tradition, the construction of the Dormition Cathedral in Kiev is noted with the transfer of the Kiev Caves Monastery founded by Venerable Anthony and the capital city of Kiev itself under the direct patronage of the Theotokos: “I wish to build a church for Myself in Rus, in Kiev... I will come and dwell in it.” Thanks to this dedication to the Theotokos, Professor V. Rychka believes, the capital of Rus’ was perceived by the medieval public consciousness as a God-chosen and God-protected city—the House of the Theotokos, a sacred symbol, and the heart of Holy Rus’, thus ensuring the spiritual unity of the entire Russian land.

Thus, the Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” on Mt. Athos became the archetypal center of the sanctification of the Kievan Rus’ land. Following its spiritual unity and kinship, an “image” or “icon” of Holy Mt. Athos—the Holy Dormition Kiev Caves Lavra—was recreated on the Kiev hills, and the Kievan Rus’ land itself earned the honorable name of Holy Rus’.

The spiritual father and first steward of the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery on Mt. Athos, Hieromonk Macarius (Makienko), rightly notes:

“There are spiritual threads that visibly connect the Kiev Lavra with the place of the labors of its founder on the Holy Mountain—the Dormition Church, at whose altar he took monastic vows, and the command from the abbot to go to Rus’. The Great Dormition Church of the Caves Monastery, built according to the design shown by the Queen of Heaven to the Greek architects—is it not a symbolic projection of the first Russian church of the first Russian monastery on the Holy Mountain, where the founder of Russian monasticism and the founder of the Kiev Caves Lavra labored?”

Remarkable is the significance this cathedral has acquired for the Russian land. The Dormition Church became the main cathedral of Rus’, a cathedral of the highest importance, a common Russian shrine—for no other domestic church is named, as it is, the “Great Dormition Church”. This name connects it with the Great Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and the Church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem. Interestingly, the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev—the official central cathedral of Kievan Rus and the seat of the metropolitans—did not receive such an honorable designation. The secret, it seems, lies not only in the miraculous features of the construction of the Caves Church—such miracles often occurred in the construction of other churches—but in the symbolic significance it carried and still carries as a connecting link between the two Portions of the Theotokos—Holy Rus’ and the Holy Mountain—and highlighting the continuity of the first from the second.”

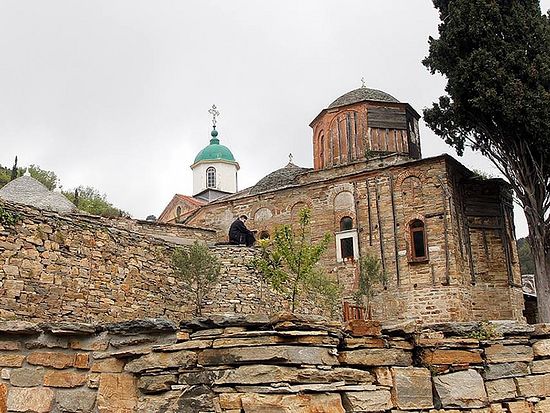

Ksilurgu Skete. Sergei Shmel Speaking of the ancient Russian Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” on Mt. Athos and the tradition that St. Anthony of the Caves labored and took his monastic vows in this monastery: In the catholicopn of the Dormition of the Theotokos, it is important to note that this monastery was the center and school of Russian monasticism on Mt. Athos. It is doubtful that the newly converted Rus’, who did not speak Greek, would settle in foreign Greek monasteries on the Holy Mountain. That is why soon after the Baptism of Rus, a Russian monastery was founded on Athos.

Ksilurgu Skete. Sergei Shmel Speaking of the ancient Russian Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” on Mt. Athos and the tradition that St. Anthony of the Caves labored and took his monastic vows in this monastery: In the catholicopn of the Dormition of the Theotokos, it is important to note that this monastery was the center and school of Russian monasticism on Mt. Athos. It is doubtful that the newly converted Rus’, who did not speak Greek, would settle in foreign Greek monasteries on the Holy Mountain. That is why soon after the Baptism of Rus, a Russian monastery was founded on Athos.

The first known written mention of this ancient Russian monastery on Mt. Athos dates back to 1016. Under this date, in one of the Athonite documents stored in the library of the Great Lavra of Athanasius the Athonite, the signatures of the abbots of all the Athonite monasteries appear. Among them is an inscription: “Gerasimos, a monk, by the mercy of God, a presbyter and abbot of the monastery of the Russians. Personal signature.”

Thus, the first known and documented mention of an ancient Russian monastery on Mt. Athos and its abbot dates back to 1016. There is no doubt that this was the Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu.”

Ksilurgu Skete. Photo: Sergei Shmel

Ksilurgu Skete. Photo: Sergei Shmel

It was here, according to tradition, that the father of ancient Russian monasticism, a native of the Chernigov land, Venerable Anthony of the Caves, took his monastic vows. Later, by the blessing of the elders of the monastery, he transferred the Athonite rule to Rus’, founding the Kiev Caves Monastery according to the Athonite model, and it became the center and school of ancient Russian monasticism and enlightenment for all of Rus’. “Lord, may the blessing of Holy Mt. Athos and the prayer of my father who tonsured me be upon this place,” Venerable Anthony declared at the site of the foundation of the Kiev Caves Monastery.

Who was this great elder-abbot who tonsured Venerable Anthony and whose blessing played such a decisive role in the fate of not only the Kiev Caves Monastery but the entire Russian Church and Rus’ itself? This question remains open. However, it is most likely that he was that same Venerable Elder Gerasimos, “presbyter and abbot of the monastery of the Russians,” the first abbot of the “Ksilurgu” monastery, who left his signature on the above-mentioned act of 1016.

From the hagiographic lists, it is known that Venerable Anthony (in the world Antipa; born 983) arrived on Mt. Athos at a very young age (around 1000). By 1013, he returned to Kiev from the Holy Mountain for the first time. After staying in Kiev for a short time, in 1015, due to the internecine turmoil following the death of St. Vladimir and the murder of Sts. Boris and Gleb, he returned to Athos, where he labored until his final return to Kiev (according to some sources, this happened after 1030; according to others, after 1051).

In any case, it is evident that the father of ancient Russian monasticism began to labor on the Holy Mountain before 1013. Such journeys from Rus’ to Mt. Athos at that time could not have been undertaken alone. Therefore, undoubtedly, Venerable Anthony was accompanied by other companions on such distant and dangerous travels. All this confirms that the first Russian monks appeared on Mt. Athos long before 1013. It is likely that they formed the brotherhood of the first ancient Russian Athonite monastery in 1016, whose abbot was the aforementioned Gerasimos. It seems he was the spiritual mentor and elder of young Anthony, who tonsured him into monasticism and later blessed him to establish a “representation” of the Athonite Holy Dormition Monastery in Kiev.

The successor of Venerable Abbot Gerasimos was likely Abbot Theodulos of the “Rusicon,” who left his signature on the mutual act of the Esphigmenou and Ksilurgu monasteries in 1030 (here the names of their abbots are mentioned: Theoctistos and Theodulos. See: Acts of the Russian Monastery of St. Panteleimon on Holy Mt. Athos. Kiev: Printing House of the KPL, 1873, p. 3). A copy of this document is still kept in the archive of the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery on Mt. Athos. It is likely that under the new abbot Theodulos, Venerable Anthony finally returned to Rus’ and founded the Kiev Caves Monastery in honor of the Dormition of the Theotokos, in imitation of, or perhaps initially as a “representation” or “branch” of the Athonite Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu.”

It is known that the Russian monastery on Mt. Athos originally had the status of an Imperial Monastery—a status not held by all monasteries at that time. The monastery may have been a gift from the Byzantine emperors to the prince of Kiev. The Russian monastery had the right to appeal directly to the emperor, bypassing the Protaton of the Holy Mountain. From 1030, it was given the title of Igoumenary (Act 1), and in the imperial decree of 1048, it was called a Lavra (Act 3). Already during this period, the “Rusicon” had a developed economy and employed workers. It had a pier, ships, arable land, a mill, and its own road from the pier to the monastery.

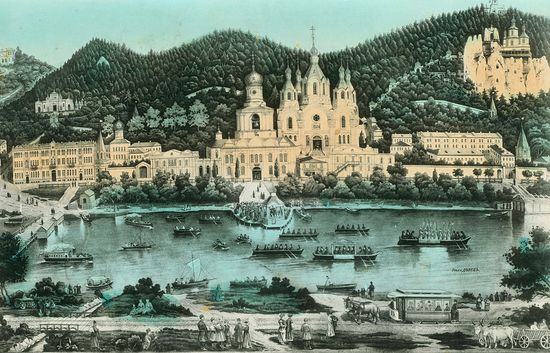

From the beginning of the eleventh century, the Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” began to carry out its mission of spreading the Athonite spiritual heritage in Eastern Europe. In addition to Venerable Anthony of the Caves, there were other ascetics who carried the Athonite tradition to the Slavs. Based on the life of St. Moses the Hungarian († 1043), it can be asserted that after 1018, a Russian hieromonk from Athos was sent to Poland, where he tonsured Moses into monasticism. In 1225, on Mt. Pochaev, the Russian Athonite ascetic Venerable Methodius founded the future renowned Holy Dormition Pochaev Lavra. The place where it is located is still called, “Holy Mountain”. In the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, some Athonite monks settled in the chalk Mountains on the banks of the Seversky Donets, laying the foundation for another Dormition Lavra, which later became known as Svyatogorsk (which means, “Holy Mountain”).

View of the Holy Dormition Sviatogorsk cenobitic monastery, Kharkov governate. Lithograph, 1912.

View of the Holy Dormition Sviatogorsk cenobitic monastery, Kharkov governate. Lithograph, 1912.

All three renowned monasteries are connected to the Holy Mountain, named after the Dormition, and marked by special providence of the Theotokos. They were all founded by Russian ascetics from Mt. Athos at approximately the same period—before the Mongol invasion. Sources do not specify exactly from which monastery on the Holy Mountain they came. But the time of their mission coincides with the period of flourishing of ancient Russian monasticism in the Ksilurgu Monastery on Mt. Athos. Therefore, most likely, all these Russian Athonites came from one ancient Russian Lavra on Athos—the Holy Dormition Monastery of the Theotokos “Ksilurgu.”

During this period, the Russian Athonite monastery was so frequently replenished with new inhabitants from Rus’ that, no longer fitting in the original monastery, it began to acquire impoverished and abandoned cells and small monasteries in the vicinity. In 1169, the Russian Athonites purchased from the Greeks the nearby ancient monastery of “Thessalonian” in the name of St. Panteleimon the Healer. Thus, the main part of the Russian brotherhood from Ksilurgu moved to a larger monastery of “Thessalonian” (now known as “Old Rusicon” or “Rusicon on the Mount”), which is on the old road connecting Karyes with the current Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery on Athos. Simultaneously, the Russian monastery was allocated cells in the capital of Athos, Karyes, by the Holy Kinot. As for the former location of the monastery—Ksilurgu—it was not abandoned. The monastery was transformed into a skete, which remained under the jurisdiction of the Russian monastery. It still belongs to the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery on Athos.

Interestingly, when the Russian monastery on Athos moved to a new, more convenient location in 1169, according to tradition, it recreated the symbolically important for Rus’ Dormition Cathedral, which held special spiritual significance in the Russian ecclesiastical consciousness. Hieromonk Macarius (Makienko), spiritual father and first steward of the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery on Athos, writes about this: “The significance of the Dormition Cathedral for Russian monasticism is indirectly evidenced by the following facts. When the Russian brotherhood moved to the more spacious ‘Thessalonian’ monastery (Old Rusicon on the Mount) in 1169 under Abbot Lawrence, the Dormition Cathedral of the Theotokos Monastery was reproduced there. And more than six centuries later, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, under Abbot Savva, when the new so-called Coastal Rusicon was built, the Dormition Church was again transferred there, retaining its status as a cathedral.”

Reflecting on why this church is important for Russian monasticism both on the Holy Mountain and in the Fatherland, Hieromonk Macarius notes that it is memorable “precisely because the first Russian lampada on Athos was lit in it; because at its altar, the father of Russian monasticism, Venerable Anthony, took monastic vows; because it was from here that he received and transferred the blessing of Holy Mt. Athos to the Russian land and thus forever united Rus and Russian Athos with the bonds of spiritual grace-filled continuity.”

Thus, the Russian Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” on Athos became the spiritual-historical link that closely connected the newly enlightened Kievan Rus’ and Holy Mt. Athos. It was from this monastery that 1,000 years ago, Venerable Anthony of the Caves first transferred and established Orthodox monasticism in Rus. Under its influence, the Kiev Caves Monastery emerged, becoming a kind of “nursery” of Athonite heritage, Orthodox monasticism, literacy, and enlightenment in Rus’. Since then, Athos and its spiritual traditions have played an exceptionally important role in the development of the spirituality and culture of the East Slavic Orthodox peoples for many centuries, influencing their originality and uniqueness. Essentially, Holy Mt. Athos and its heritage have had a fundamentally beneficial impact on the formation of the mystical-ascetic character of the unique ancient Russian Orthodoxy, as well as Holy Rus’ itself. Repeatedly, the Holy Dormition Monastery “Ksilurgu” on Athos played a decisive role, giving Kievan Rus’ Venerable Anthony of the Caves and many other ascetics and enlighteners.

St. Anthony of the Kiev Caves in the refectory cave church of Anthony and Theodosius of the Caves in the Chernigov skete of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra

St. Anthony of the Kiev Caves in the refectory cave church of Anthony and Theodosius of the Caves in the Chernigov skete of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra

Hieromonk Macarius (Makienko) rightly notes: “The Russian land is directly connected to Holy Mt. Athos through spiritual kinship, as the Russian monastic tradition is a branch, or offshoot, of Athonite monasticism, transplanted onto Russian soil not by human hands by God’s hand. Because of this spiritual kinship, Rus’ has always had a refuge, a God-given corner in the Portion of the Most Pure Virgin Theotokos—a Russian monastery, which was evidently preserved by Divine Providence, judged, and destined to be the heritage and patrimony of our compatriots seeking salvation on the Holy Mountain.”