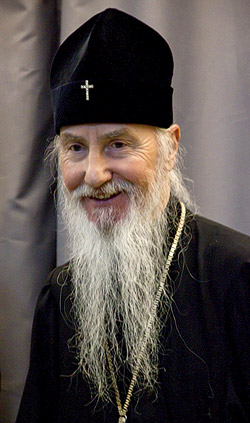

The Orthodox parish today, both in Russia and abroad, is becoming more than just a place for prayer, but also a local center for socio-cultural life. His Eminence Archbishop Mark of Berlin, Germany and Great Britain spoke to the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate (no. 8, 2011) on the problems and challenges facing parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.

— Your Eminence, what are the challenges facing today’s Orthodox parishes, especially those in Germany?

— First of all, the challenge is to strengthen faith in those who believe, and to help those who have no faith to acquire it, that is, to churchify the baptized Christians who still don’t observe religious rites.

Many such people who are from Russia come to our parishes. And here, in the diaspora, their Orthodox hearts are awakened: they come to the Church. I must say that in comparison with the general population, not many attend church, just like in Russia, where a smaller percentage of people participate in divine services.

So our primary challenge is missionary work. This demands work, with both the baptized and un-baptized, with Russians and with the Germans among whom we live.

— Can you tell us about the problems facing the parishes of Germany?

— There is no end to the problems. Mainly, as I said, these involve the fact that people come to us now who are completely different from the people who came in the 1990’s.

Back then we saw people who “grew into” the Church organically, since they came from believing families, or they had been with us since the end of World War II, who still had some roots here and became part of the Church. In the 1980’s and early 1990’s, when the last generation of people who were raised in the Church departed into the other world, Russian society changed. We have an acute sense of this. So we have the challenge of bringing people who came after the 1990’s into the Church, and secondly, we face the problem of acquainting them with our church traditions, since, of course, they have their own characteristics, including those of language.

The next problem is the attitude our faithful have to other Christians and those of other faiths. We cannot ignore the fact that our parishioners come from different places. In addition to immigrants, we have scholars and students. So each parish has people who understand things in very different ways, and so they need different, individualized treatment. So both clergymen and those who help in church must take into account not only different viewpoints in the explanation of the truths of Orthodoxy, but also the knowledge of language, or lack thereof, and a great deal more.

Another big problem is the attitude of the parishioners to those of little or no faith. We have many families that have people of different confessions. It is very rare when everyone is of the same religion. Sometimes there is only one Orthodox Christian in the family. On Sunday they rush to church to take Communion, but they are expected back home at noon for family lunch, which means they cannot take Communion, which is only offered after twelve. This is one of a whole series of problems, among which is the ban on speaking Russian in some families.

In other words, we are faced with many problems which are different from the problems of parishes in Russia. Let us take the cultural level of our believers. Unfortunately, we are witnessing a powerful, rapid fall of the use of the Russian language. Children who are now 10-12 years old barely speak Russian. For them, it is the language they speak to their mothers in the kitchen is not their everyday tongue. Teaching such children, bringing them close to Russian culture is very difficult, demanding a great deal of flexibility, in order to preserve their interest in everything Russian, Slavic, often switching to the German language as necessary.

A priest who speaks the local language fluently can easily maneuver between his Russian- and German-speaking parishioners. But a pastor who does not have a good command of the language can with time lost his young parishioners.

Another problem is the fact that Orthodox Christians in Germany have to resist the surrounding heterodox culture. The more educated a person, the easier it is to for him to argue his viewpoints, to defend his faith. That is why the role of a priest and parish are to support the parishioners, to teach them to defend their views.

— You said that there is no end to the problems. What is the situation with clerical personnel who should address this challenge?

— The lack of qualified personnel in the Church is an eternal problem—it is likely to last forever. The question is can we do anything about it? Germany happens to be a special place in this regard—we have the largest influx of officially baptized people from Russia anywhere in the diaspora. Most of them are not catechized, and so we are faced with problems which neither America nor Australia face, or anywhere else.

Of course, we need priests, but where are we to find the resources to support them? In Germany, you could open a parish in almost every town, which wasn’t the case before 1990. One could even establish parish communities in prisons. But at the same time, there are few places where the people would be active enough to organize a community, to invite a priest and pay him a salary. That is why we are constantly dealing with the financial challenge.

We are getting a handle on this now. Our parishes support their priests, but only barely—still, they do. The question is if you have the money to pay a priest, by all means, we’ll find one for you! So the problem is tricky but solvable.

— How do you think the Moscow Patriarchate might help in this regard?

— We do turn to them now and again. We can obtain priests from Russia, but this is always very difficult. Find me a priest in Russia who speaks at least some German, English or French. Such people are very rare. One must not only know the local language, but also the psychology of the immigrants, their life circumstances, their problems, what they bring to confession after moving abroad. If you don’t know them, what can you say?

That is why I always said, ever since I began my archpastoral service, that a diocese that cannot supply its own priests is poor indeed. We must strive towards educating our own priests, and only then can we properly minister to our flock. This isn’t always possible. But, thank God, we do see success now and again.

— How do you envision the future of the parishes of the German Diocese?

— That all depends on us clergymen. The amount of work we put in will determine the results. We have fertile soil—but we have to work it. How are we doing in this regard? I think we must to a great deal more. At the same time, I think that each priest does everything he can. Though maybe he needs a nudge once in a while, supplied with new ideas, new ideas for pastoral work.