|

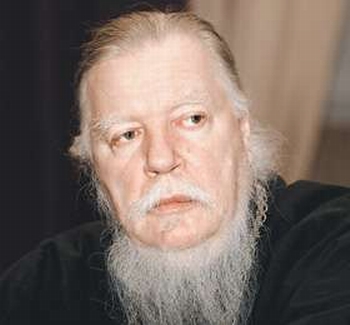

| Протоиерей Дмитрий Смирнов |

Here’s why. Because the essence of Christian teaching gets through to a person with great difficulty, it is much easier to follow the route of strict instructions. This is an everyday problem for clergy and laity alike. Afraid of all kinds of responsibility and continually in doubt, a human being seeks some kind of concrete, clear instructions—what is permitted and what is forbidden. The majority of people are caught up in this—how to equip yourself with some kind of simple, comprehensible instructions by following which you can calmly save your soul. Well, unfortunately there are no such instructions. In order to save your soul, you must understand what God’s will is, both in general and for you personally. For that you have to exert pressure on your soul, and mind, of course. And we aren’t very suited to this labour of soul and mind, due to our sinfulness. So every human being, just like every creature living in this sinful world, tries to follow the path of least resistance.

Let’s draw a comparison with a more or less able pupil at school. After he’s been asked to do something in class, he’ll switch off from studying for a month or so: “I’ve got my mark and I’m not being asked anything.” Then, when his turn comes round again, he starts reading up, so that the moment he’s asked he will answer and again create the impression that he knows something, although in the interim his mind was absent. Maybe he was physically present in class, but he was absorbed in his own thoughts, or in chatting to his mates, or with what was going on in the playground. He pays attention only at intervals. If you ask him why he goes to school, he’ll say that he wants to find out about the world, get qualifications and so on, but in fact he strives only to create a good impression.

This is the easiest path to follow. There are two more—the first is the hardest, it is when a person does his homework every day even when he is sure that no one will ask him about it. That is the responsible path, a person doesn’t think about what he’ll get for it but what he will get out of it. And then there is the third path, of complete denial. “Don’t know, wasn’t there, forgot my diary, was off sick, no one told me, my granny was ill, there weren’t any buses” etc. etc. That is the path of the majority. And this continues when the pupil leaves school and becomes an adult, because Christianity is also a form of learning. However, it doesn’t just concern the faculties of the mind—memorising, reasoning, summarising and so on—these are all used, but they aren’t the main thing. The main thing is to have a deep understanding of what is required and to direct your will towards doing it. Because this form of learning, of discipleship, is without coercion, it is higher.

In school there is usually pressure from parents and teachers, who use pedagogical methods to coerce a pupil into studying. At college there’s less of this, but it’s still there—a student is pushed by being told that he’ll get a higher grade or lose part of his grant or encounter some minor difficulties. Not here, though. Every person who is born into this world and is baptised in church makes a promise to God: Do you reject Satan? I do. Or, if he was a child when he was baptised, then he didn’t reject anything, but adults promised on his behalf, promised to God that he’d be brought up in a Christian way. The promise is serious, of course, but a person remains free just the same. Are you in control of your own will? You are. Today you give your word, tomorrow you take it back. No problem. The day after tomorrow you give your word again, and the day after that you take it back again. And so on, and on. If I want to, I give my word, if not, then I take it back.

This is how people usually behave, or, more frequently, this issue does not exist for them at all. They just live with completely different problems of different sorts—family problems, problems concerning food or clothes, relationships with other people. But relations with God do not figure anywhere. Then, of course, there is a world of people who don’t go to church, sensing in advance that it demands too much responsibility. Here quite peculiar things happen. If you ask a couple why they don’t get married, they say, “Well, it’s a big responsibility.” You know, living together, having children, owning joint property, that’s all nothing. But getting married? What if something suddenly happens? They are scared of responsibility, even though in reality they have already taken it on—before God, before other people and the law they are already man and wife. But they just can’t go through with this last stage, which is something that they have thought up themselves, because marriage starts when she thinks he is my husband and he thinks she is my wife. Sometimes it doesn’t coincide. After every census it turns out that there are more husbands in the country than wives, somehow, she considers herself married and he doesn’t. He doesn’t tell her, of course, so as not to cause problems, but within himself he made up his mind long ago. Sometimes he tells her, now everything must change, and she says, how come? He says, it just happens, it’s called falling in love with someone else. There’s nothing to be done about it, get your stuff together.

And so a person is afraid of this kind of responsibility. On the one hand it’s justified, because responsibility before God is indeed very great. As a baptised person, however, you have that responsibility, you can pretend that you don’t have it, but it’s there just the same. Even if you’re not baptised, if you’re Muslim or atheist, you are responsible before God having been born into this world and you can’t hide behind postulates you’ve thought up or read in some book or other. Because that happens—although a person usually says “I think that...” there are actually a handful of people in the world who have thought up something independently. Most people give themselves over to the spirit of the age—“as the majority does, so do I”—while, interestingly, this majority might actually be a minority out of the whole six billion mass. Nevertheless, every person, even a hermit, regards himself as belonging to a certain circle, and whatever is considered the rule in that circle is how he behaves, all the while under the illusion that this is his opinion and he thinks what he likes.

In actual fact nothing of the sort happens. A person is entirely dependent upon upbringing and surroundings, and mostly on his passions. He is completely dependent, even in his relations with others. Say he has a good relationship with someone, friendly and warm. And suddenly someone else says to him, you know, that friend of yours said such-and-such about you. Wham! The relationship changes instantly. But what’s changed? As the other person was before, so he remains. Nothing has changed in HIM. And what? A piece of information, not clear if it’s true or false, and even if it was like that—he really did use exactly those words, in that tone of voice—although there’s always some distortion in the telling—nevertheless, what’s changed? The person’s the same. Why has the relationship changed? Because the person said that thing about you. And what if he didn’t say it, but thought it? You would never have found out. Nothing has changed, but the relationship has changed. And due to such petty incidents—someone said something and another person passed it on—everything changes.

Interesting—everything changes due to petty incidents, but as a result of what a person promised to God at baptism nothing changes. The question arises—so where is responsibility? Maybe it isn’t the absence of responsibility, but something else? It is indeed something else. A person is subject to a great many false notions, not connected in any way with spiritual life or religious things. There are social conventions which people follow that are bad for them—some are good, some are bad—but a person is afraid of breaking them for fear of what other people might say or think about him, or that he’ll be judged.

So why is a person dependent upon such things? Why does a person depend so much upon human opinion? Because most people are used, not to being someone, but to appearing to be someone. And this appearance is much dearer to a person—how other people see him—than how he is in actual fact. But genuine responsibility lies in who you really are, who you are before God. Because two people, even if they’re man and wife, can never know each other right through due to our corrupted human nature. In the beginning it wasn’t like that, Adam understood everything absolutely. All humanity had that ability—but due to the Fall and exile from Eden it was lost, and many centuries and millennia down the line we have lost that ability even more. And so Christ comes into the world in order to restore our fallen nature, to give us that possibility.

But a person resists, going along the route of a search for instructions. Father, am I permitted to or not? Grant your blessing, and I’ll go, if not, I won’t. Can I eat this during a fast or not? He needs a sanction, but why? So as to put the responsibility onto someone else, onto a sort of sacramental figure: Let there be one who decides everything for us, to go in our place, the main thing is not to have to think. Why? Because my head hurts, I don’t feel like learning, because it’s difficult, because it requires a great deal of effort, and a person longs to relax.

Well, indeed, what’s easier—to hold a bucket of water for ten hours with your muscles straining, or to lie down? Of course, the muscles strive for relaxation, just like the muscles of the mind, of the soul, of everything. So Christian learning or discipleship leads us to heroic feats, but sin makes us relax, to make concessions, to swim with and not against the tide. So that’s why there’s this dependence upon people, upon a circle, upon opinion, because if there is a tide, it’s much easier for me to swim with it. But to climb up onto a cross and have your hands and feet nailed to it—I don’t feel like doing that.

And so, in order to still his conscience and adhere, at least formally, to a certain idea or dream, a person searches for some kind of instructive secular surrogate. Maybe I’m poor, maybe I’m stupid, maybe I’m a gossip, but at least I’m an acclaimed writer. What was your name again? Never heard of you, but still, it doesn’t matter, acclaimed, don’t know what for or by whom, the main thing is, acclaimed, maybe no one knows or has ever read a single book, but I’m a member of the Tula regional writers’s union, earlier there was one Leo Tolstoy, but now there are 32 members, wonderful, some kind of progress is taking place on the literary scene.

This dependence upon instructions isn’t at all accidental, it is absolutely psychologically conditioned. A person always wants, if not to become something, then to receive some kind of position, or renown, or award, or a bouquet of flowers on his birthday. It isn’t important if a person likes me or not, what counts is that I receive signs of attention. And a person often surrounds himself with all this to such an extent that his internal essence is suffocated or lost, and a particular world appears which exists parallel to the real world: hypocrisy, behind which there lies nothing. That is why the Lord says: “Woe to you hypocrites!” He is not addressing particular people, but all of us, for this is characteristic of our fallen nature. There is no need to think that there are particular people with this particular sin, no, it is our absolutely universal characteristic. So where is the danger here? The danger is that, as a result of all this, each of us does not live a genuine life, but in this field of illusions. And that we waste time on this, waste energy, waste our minds thinking up all these never-ending things.

But there are no instructions, not even from the highest authority. Normally on official instructions there’s always a signature in the corner—“I hereby confirm that...”—and some high-up person has confirmed it. Instructions like the Law of Moses have two authorities—prophetic, because the prophet Moses went up onto Mount Sinai to receive them, and the Lord God himself, who gave them, but they are still only instructions, even if they are of the highest kind. St Paul is saying that they do not save—if you don’t kill, if you don’t steal, if you don’t commit adultery, if you honour your father and mother, if you set aside one day of the week for God, if you don’t make yourself idols but really worship the one true God, nevertheless, you won’t save your soul. That you go to church once a week and don’t steal, don’t swear, don’t lie, don’t bear false witness, don’t envy—all this, it turns out, doesn’t mean anything at all, it doesn’t come near enough. It is all very good and proper, but it isn’t enough. You need faith as well.

But why is faith necessary? Why is faith in Jesus Christ necessary? Namely in Jesus Christ, because people understand this and say, well, you must believe in something. Well, let’s believe in this felt winter boot here—what is there to believe in? Put it on, walked around, stayed warm... but to believe in Jesus Christ requires responsibility, because you need to re-align your life from the material to the spiritual—and without receiving anything material in return here on Earth, but only slander and persecution. If you’re successful, you’ll even be killed, just as Jesus Christ was killed, as all the apostles and martyrs were killed, as all the saints were hounded. Now you hear: “Oh, St Seraphim of Sarov, let’s say a special service dedicated to him.” But when he was alive—what he didn’t have to put up with! And from his own abbot, and from his fellow monks, and the lay people who came to see him, and the peasants whom he helped but who beat him half to death and made him an invalid. What sort of life did he have, and for what? Because he was a Christian.

That is responsibility, that is faith, when a person agrees to put up with that for the Lord, for the sake of a higher life which he doesn’t even know. Because at first comes faith, then grace. The Lord says, if you give money to a person and then expect it to be returned, what sort of grace do you have? Give, and forget that you have given it—then maybe that material will turn into the spiritual. First sacrifice, then grace. But the Lord isn’t satisfied with us sacrificing something to him—a bit of money, some candles or something given to someone every now and then. Again, for the Lord’s sake, it is all very good. No, the Lord wants us to give our whole lives to Him—but why does He want so much?

Well, for one, our lives belong to Him anyway, as He’s our Creator. Secondly, what a person receives in grace outweighs the contents of our lives many times over. It is not an equal exchange. God gives us much more than we can sacrifice to God, that’s the thing. And He expects us to understand this. And we, poor things, want to get out of it. If we want awards, then we want them from people, if recognition, then from people, if justification, then from people, if praise, then from people. And we aren’t scared when the Lord says that if a man has already received his reward here on Earth then that’s all he’s going to get. The Lord says that our left hand shouldn’t know what our right is doing, that God sees what you do in secret and will reward you for it. That is, no one except for God should know about what you do for His sake, or for your neighbour’s. Not even your neighbour. But if we give away a penny, we shout a pound’s worth about it. We boast about it until everyone is fed up with hearing about it and the good deed loses its sense entirely. And as for the person to whom we do the good deed—we always shove reminders in his face, so that he starts to think that he would have been better off if he hadn’t asked for help in the first place, he’s so sick of hearing about it.

And then, it turns out, we didn’t do it for God’s sake after all, but to gain control, to make other people dependent upon us. It seems like a person selflessly helps out, but then he demands something back in return. But if some kind of gain is involved, then you’ve already profited, so where does God come in? You want to receive from this person and from God as well? Sell the same goods twice over and so receive double the money? But that’s swindling by any criminal code, you’re a swindler and not a Christian! And so we turn our Christianity into swindling. Here again, this is in all of us. There’s no need to take offence with each other for it, it is characteristic of fallen human nature. We shouldn’t get despondent about it, we need to fight it, to try to unite our split lives, our common schizophrenia, so that we lead a whole and not a double life.

To do this we need a great deal of spiritual energy, for which, of course, we need to pray continually and patiently to God. But prior to us the Word of God, in his kindness, came to Earth—not in the form of a book, but as a person, Jesus Christ. Why? Because the majority of people on Earth aren’t bookish, it is very difficult for them to receive the Word via some kind of combination of letters. Moreover, many such people have a higher education, there are even doctors of science who have big problems in reading a book—the person sees familiar letters, they form a sentence, but the mind doesn’t work very well. To make sense of it all is for a very small group of people.

That’s why the Lord took human flesh. Often the apostles don’t tell us what the Lord said: “He preached about the Kingdom of Heaven.” Why? Because they don’t remember, they forgot. That’s right, they forgot the most important things that He said. But they remember what they saw Him do, and there was great meaning in what He did, which you can also draw from His teaching. When He wanted to draw special attention to something, He always said: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, let those who have ears hear.” That is, “may they hear,” but it isn’t compulsory for everyone to hear. That is why the Word of God has been active in the world for two thousand years, but far from everyone hears it. A person needs some kind of other ability to acquire it, for it to reach the human heart. Because the sin which divides us from God forms a great obstacle on the path of His Word to our heart. The Lord talks about this in the parable which we read today, a parable which we all know very well.

It is the parable about the sowing of the seed. Some was sown on the path and the birds took it, some on the stones and it dried out, some between thorns, which suffocated it and more on good soil, where it bore fruit. Thus, sometimes whatever we have read or heard in church goes in one ear and out the other—the birds took it. More on the stone: Oh yes, how well said, great! But get to the bus stop: What was it about today? Don’t even remember what the gospel reading was. That is, there for an hour or so and then it withers away. Then in the thorns. Got home, right, start a new life, excellent! Try hard until evening but then—guests are coming, wash the floor, mend the window, defrost the fridge. Concentrate on worldly affairs and it’s all wiped away, and if you argue or watch something bad on TV—then everything that was in your soul is tarmacked over. And only if one of the seeds falls on good soil does something in life really begin to change. Only that can bring forth some kind of fruit.

Because the sense of someone baptising us at some point, the sense in the Lord bringing us to church—what’s the aim of it? Only one. So that we change, and not in our own eyes, but in a certain direction, in accordance with the Word of God, by bringing our path to God, so that it leads us to heaven by God’s grace, that’s the point. Not just standing out the service, sweating, toiling, listening, having a break and then going home to our clothes and objects and envy and discord, to our arguments over money and all the other things which make up our lives. If that is not the aim, then it doesn’t count and no instructions will save us.

It’s ridiculous—a person doesn’t buy a plane ticket because there’s a barcode on it. He’s afraid of it. But aren’t you afraid of judging your neighbour, if Christ himself said: “As you judge, so you will be judged”? A person isn’t afraid of that at all. But he is afraid of a mark, as if it were anthrax. Why? Because the lines are visual and external, it’s easy to go around some kind of line, even a hedgehog understands that. But judgement? For that you need to understand that you’re a sinner, worse than all, that if you judge someone for something, then you commit that sin yourself, because if you don’t have that sin in you, you can’t see it in someone else. You can only see in another person what is in you, so why are you judging others? Why does the Lord say you’ll be judged as you judge? Because in judging another you sign your own death warrant, you read out your spiritual biography, because if you judge someone for something you have that thing in you and you’ll be judged for it.

But a person isn’t afraid of that. Why? Because he despises God’s Word. It is much more important to him that someone, some elder with a beard, told him that you need to be afraid of a barcode. Why? Because the elder can be seen, touched, he’s very real. But to check if what he says is in line with the God’s Word requires the mind, it’s much easier to rely upon the elder, and seemingly let him take responsibility. Well, of course he takes responsibility just the same as if someone says to you: “Hey, throw that stone over there!” and you throw it and it breaks something—you’ll bear joint responsibility. Both participated, it’s not important who performed the action. Very often, the organiser is more guilty.

But it’s easier for a person to have instructions—you give me a list of what is permitted and what is forbidden. Such a list would fill the whole universe. Because everything is permitted—and everything is forbidden. And what is more, the very same thing might be permitted in one situation and forbidden in another. For example—can I shoot a gun? Grant me your blessing for that please, Father. Well, it depends upon what kind of gun it is, it depends upon what it’s loaded with, it depends upon when you shoot it. If you start firing at 3am and wake everyone up, is it permitted or forbidden? And if a person’s thinking is so skewed that he doesn’t understand that you can’t shoot a gun at 3am or ride a motorbike without a silencer, if he doesn’t understand that, he asks—can I ride a motorbike? So I say, yes. Then his mother comes up to me and says, you know, he rode across garage roofs on his motorbike. I didn’t know he was going to ride across garage roofs, did I? And he says, Father, grant me your blessing, please. Instructions received, blessing. But who would guess that he’s going to ride across garage roofs? Break his legs, damage the bike, other people’s roofs. You’d think—he’s going to ride it in the woods where it’s quiet, on tarmacked paths, at a normal speed so as not to break his neck. That’s what you’d think, but he had something entirely different in mind.

And who, apart from God, can know what is in a person’s head? How can one person decide for another? A person comes and says—what should I do? What can the other person say? How should I know? I don’t know what I should do, and you come telling me that I should know what you should do. And you’d need to be crazy to take responsibility for another person. A person comes to the doctor and says he’s in pain. The doctor says—how do I know where it hurts? Maybe you broke a rib 15 years ago, or you’ve got neuralgia, or you just think you’re in pain, you’re starting to go round the twist—that’s also possible.

You need to examine everything thoroughly, that’s Orthodox responsibility. It’s a very serious business, you need to put a lot into understanding what’s going on, not just take a pill and calm down. So does that mean that saving a drowning man, so to speak, is in the hands of the drowning man? No. It is God’s affair and it lies in the relationship between a person and God. And the search for the path to the truth does not lie in some sort of exterior authority, but in the personal relationship between every individual and God. That’s what you need to look for, and that is genuine spiritual life. Because, by definition, spiritual life means life with God.

So, if we acquire that we acquire everything, that’s why we need to search for it. There are many ways to it—they aren’t all different, there is one path, but there are certain approaches—prayer, good deeds, reading God’s Word. But it demands colossal effort and colossal responsibility, we can’t simply relate to the Lord’s parables purely formally, we need to make an effort, to exert our soul, to exert our mind, so that change is born in our lives. If that change doesn’t take place, then it means that our Christianity is just empty and superficial, it must have practical application in our lives.