SOURCE: BBC Religion&Ethics

By Flavia Di Consiglio

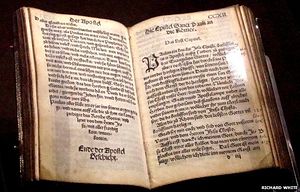

Translating the Bible can be a revolutionary act. In his German version, Martin Luther used a simple language, as he believed that everybody should be able to access the Scriptures.

When scholar and priest William Tyndale decided to translate the Bible into English in the 1520s, he set out on a dangerous journey that eventually led him to be burned at the stake.

At the time, the only authorised Bible in England was a 4th Century Latin version, and translations were forbidden. Tyndale's crime was an intense desire to see his fellow countrymen read the Bible in their own language.

Five hundred years later, Bible societies around the world are pursuing the mission of having the 'Book of Books' translated into every single language known to man, and the number of new versions grows every year.

According to the United Bible Societies, the complete Bible has been translated into over 475 languages, and the New Testament into more than 1,240.

Bible ban

Oldi Morava, a translator for the Bible Society, was born in Albania, where the Bible was not always welcome.

All religious observance and education were banned in 1967 when the country, led by Stalinist dictator Enver Hoxha, was declared the first atheist state in the world. The ban was not lifted until 1991.

Even Bible smuggling was too dangerous: "The persecution was so brutal that people were very afraid to get involved in anything like that," says Mr Morava.

He embraced Christianity when the communist regime in his country collapsed. He was only 11 years old: "At that time, we had quite a hunger for Christianity and God," he recalls.

"We would be reading whatever we had, although we had quite a limited amount of books about Christianity."

Mr Morava moved to the UK to study theology and is now one of three linguists working on an Albanian version of the Old Testament: "It's an interconfessional translation, which means that the translators are from different church traditions," explains Mr Morava.

He represents the Protestant Church, while his colleagues belong respectively to the Orthodox and the Roman Catholic Church.

This is the first time that the Old Testament is being translated from Hebrew into Albanian by an interconfessional group of translators. There are other Albanian versions, but most of them have been translated either from Latin or Italian.

But forget translating fragile, ancient scrolls in a remote monastery, waiting for divine inspiration to strike: "I spend most of my days in front of a computer screen," says Mr Morava.

"Bible translation doesn't have that romantic [aura] that it had in the 15th Century," says the translator as he describes the sophisticated software he uses daily.

The invisible translator

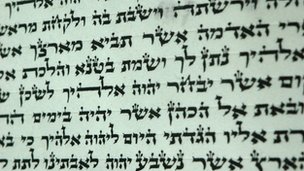

A section of the Torah in Hebrew from the Dead Sea Scrolls

A section of the Torah in Hebrew from the Dead Sea Scrolls However, the pressure is even higher for a Bible translator: "Knowing that you're translating a text that is considered holy or God's word, you somehow put a limit to your own work," says Mr Morava.

"I want [the audience] to find the voice of their God in the text that I'm translating. Therefore I have to be very careful to consider the theology of the community that's going to read it, their concerns, their desires, their passions - their God."

This is made slightly easier by working in an interconfessional translation committee, says Mr Morava. The goal is not to produce a "clinical text", but to represent the three confessions equally, and to make sure that the translators do not leave their theological imprint on the final version.

Mr Morava gives an example of how this delicate balance is achieved, citing the concept of redemption. It is an important aspect of Protestant theology and refers primarily to the event of the crucifixion, whereas, says Mr Moravia, it does not find a lot of favour among the Eastern Orthodox Church.

"The Old Testament speaks often of God redeeming Israel from Egypt," says Mr Morava.

"A Protestant translator would prefer to keep this term in order to echo the redeeming act of God that finds full expression later in history in the story of crucifixion. However, an Orthodox translator finds this unnecessary and rightly points out that the use of such terminology in these verses does not make sense for the reader."

According to Mr Morava, a suitable alternative is to translate as 'saving' or 'liberating' the people of Israel from Egypt.

Translate for thy neighbour

But translating the Bible also means taking into account the religions that live side by side with Christianity: "There is a majority of Muslims in Albania, although the type of Islam that you find there is very relaxed, very nominal," says the translator.

As Albania was part of the Ottoman Empire for over 400 years, many Turkish words have entered the Albanian language throughout the centuries, and are used by both Muslim and non-Muslim people. The translation committee decided to not use these words of Turkish origins: "An example would be the word for circumcision," says Mr Morava.

He explains that there are two different ways of expressing this concept in his language: one is the word of Turkish origin synet; the other isrrethprerje, a slightly artificial-sounding, but all-Albanian word. The translators opted for the latter, as they wanted to separate the biblical concept of circumcision from the more Muslim-specific sense implied in the Turkish word.

But other translators have opted for different strategies: "There are parts of the world that translate the Bible using Muslim terminology, so it is no surprise to find a Bible speaking about Musa [Moses] and Allah [God]," says Mr Morava.

"This is done not only to connect with a society that is rooted deeply in a Muslim religion, but also for linguistic reasons. Arabic and Hebrew share many similar features as they are part of the same Semitic family, so what we might think of as a Muslim influence is just a natural translation between two Semitic languages."

The translators are hoping that their final work will reach churchgoers and non-believers alike. Mr Morava says that, at this stage, it will probably not be used by the traditional churches as a liturgical text, as that requires more work by the Church authorities to authorise it, but he hopes that will happen in the future.

Three or four different drafts are produced before the text is published. One stage even involves the local religious community and members of the public who want to give feedback on the drafts.

So how does it feel to translate the most widely read book in the world?

"It's not just a great scholarly exercise, [although] I enjoy that aspect too," says Mr Morava.

"Being a devoted Christian, it's also a privilege - and a big responsibility."