SOURCE: Russia Beyond the Headlines

In the night between the 16th and 17th of July 1918 the family of Russia's last Emperor, Nicolas II, was killed in Ekaterinburg. RBTH investigates the identities and lives of the killers of the tsar.

Nicolas II Romanov and his wife Alexandra with children (pictured L-R): Alexei, Maria, Tatiana, Olga, Anastasia. Source: Getty Images/Fotobank

Nicolas II Romanov and his wife Alexandra with children (pictured L-R): Alexei, Maria, Tatiana, Olga, Anastasia. Source: Getty Images/Fotobank Even now, 95 years after the murder of Russia's last czar, Nicholas II, we do not know precisely how many people took part in the deed. One account of the event claims there were eight, and yet another insists there were 11—one for each murdered member of the Russian royal family.

It is clear, however, that the killing squad was led by two men named Yurovsky and Medvedev-Kudrin. Both later penned memoirs in which they described in great detail the night that Nicholas II was killed: both were proud of their role in Russian history; both held important jobs until their death, and remained respected members of Soviet society.

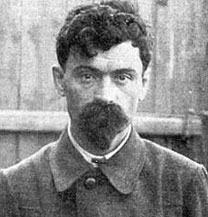

Yakov Yurovsky, chief executioner of the Russian royal family. Source: Press photo

Yakov Yurovsky, chief executioner of the Russian royal family. Source: Press photo There were, in fact, only two “foreigners” in the killing squad: Yurovsky and Tselms; the latter was of Latvian extraction, and his participation in the killing is questioned by many.

Yurovsky was a jeweller by profession, and, on the night of the killing, he was determined to find the czar’s diamonds. In this he succeeded; after the bodies of the czarinas were searched, about 17 pounds of jewellery was found sewn in their clothes. Yurovsky later handed it all over to the superintendant of the Kremlin. For the most part, the first Bolsheviks were not interested in money—but they undoubtedly were extremely ruthless.

Yurovsky later served as chairman of the Urals Regional Emergency Committee (the forerunner of the Soviet NKVD and later KGB), head of the gold directorate at the State Reserve, and head of the Polytechnic Museum in Moscow. These were all very senior positions in the strategically important first years of Soviet government.

Yurovsky died in the Kremlin hospital, which was completely off limits to all but the most senior government officials. The cause of death was perforation of the duodenal ulcer. According to eyewitnesses, he died in great pain.

They especially liked to argue over who fired the first shot that night. On one occasion, Yurovsky arrived at the party in a triumphant mood. He had just received a book published in the West, which said in no uncertain terms that he was the one who had killed Nicholas II. He was extremely delighted.

Mikhail Medeved-Kudrin, the second killers of the Romanovs. Source: Press photo

Mikhail Medeved-Kudrin, the second killers of the Romanovs. Source: Press photo In the late 1950s, he was awarded a personal pension of 4,500 rubles, which was a vast sum of money at the time. During his meetings with law students at Moscow State University, he fondly reminisced about 1918, when he and his fellow Bolsheviks had to save ammo and use bayonetes to finish the enemies of the working class.

Medvedev eventually achieved the military rank of colonel. Before his death, he wrote detailed memoirs about the murder of the Russian royal family. The manuscript, entitled "Hostile Winds,” was addressed to then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev—but it was never published. In those memoirs, Medvedev disputes the leading role of Yurovsky in the killing of the royal family, insisting that credit for the murder should have gone to himself.

Medvedev was buried with military honors at the Novodevichye Cemetery in Moscow—the most prestigious graveyard in the country. In his will, Medvedev left the Browning pistol with which Nicholas II was shot to Nikita Khrushchev.

After Medvedev’s death, his son persuaded the son of one Nikulin to testify about the events of the night the royal family was killed, in an oral statement recorded at a radio studio. It is believed that Nikulin was merely a witness of the post-mortem identification of the bodies.

Nevertheless, his son had this to say on the matter: "I remember that in 1936, when I was little, Yakov Mikhaylovich Yurovsky would visit us and write something... I remember him discussing something with my father, sometimes arguing… over who was the first to shoot Nicholas… My father said he fired the first shot, but Yurovsky insisted otherwise…"

Another member of the shooting squad, Radzinskiy, recorded his memoirs on audio tape. “One man went into the water with ropes and dragged the bodies from the water. The first body to be dragged out was that of Nicholas. The water was so cold that the faces of the bodies turned red-cheeked, as if they were still alive… The truck got stuck in the mud, we barely got it out… And then a thought came to us, and we acted upon it... We decided that this was the perfect place... So we dug up that mud, poured sulphuric acid on the bodies... defaced them... There was a railway branch nearby... So we brought some rotten railway sleepers to hide the grave. We buried only some of the bodies in the pit, the others we burned… We burned Nicholas's body, that I remember well... And Botkin's body also... and Aleksey’s as well, I think..."

In the early 1980s, KGB chief Andropov liked to listen to the testimonies of the czar-killers in the evening. Rumor has it that those audio recordings are still being held in the archives of the Russian security agencies.