Igumen Josaf (Peretiatko), a monk of the Holy Trinity Monastery in Kiev, spent seven months in the military conflict region in Iraq. In January 2005 Father Josaf took part in the 13th International Project of Christmas Educational Readings in Moscow and courteously agreed to meet our correspondent.

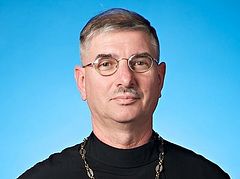

Игумен Иоасаф (Перетятько) Игумен Иоасаф (Перетятько) |

| Игумен Иоасаф (Перетятько) |

– Father Josaf, could you please tell us about how you became a chaplain?

– Honestly, I could have never imagined it would come to that. It was just God’s plan for me. The Bishop of Lvov and Galich, Augustine, who is the head of the Synodal department which is dealing with the military, is well familiar with our monastery (which is in Kiev) and the brethren. Also he knew me personally. A school branch of the Orthodox Institute of St. Tikhon was opened in Lvov with his blessing and I became one of the graduates. A need arose for a priest who also had to be a young reserve officer…

– So you have a military background?

– No, I did express service in the marines in the town of Balaklava, and then started my education at the international university of civil aviation in Kiev, I was to become a professional engineer-mechanic. The university had a military faculty, so by graduation I became an officer. The bishop appointed me chaplain, as my monastic duty. So I was conscripted by the Army as an officer, and by the Church as a priest.

– How long did you get to serve in Iraq?

– Seven months.

– What were your first impressions? Were you scared when you realized you had to go to a hot spot?

– No, without any bravado I can say that I wasn’t scared. First of all, I believed in God’s Providence and knew and thought that nothing too bad would happen. And second, I am a monk, and there is not much difference for a monk to be in this life or the next, be it a year later or a year earlier…A monk is a man who gave up a family, material well-being, worldly happiness, and most family and social relations. When a person has broken social and family ties, the ties of his own life are of not that much significance to him. Of course, before Iraq it was all words, and I still had to check the truth of those words and thoughts in action.

– What were your very first impressions? What was the first day in Iraq like?

– The first impression was the heat. It was terribly hot. Especially since we could not by any means leave the camp’s territory without body armour and a helmet.

– How was your relationship with the soldiers forming?

– From the very start I worked on the relationship of a priest and his flock with the soldiers. It was relatively simple for me, since as an officer I had certain rights, like I couldn’t be refused help. At first I wasn’t afraid, because it was quite calm. If you remember the short history of that war, you can say that the Arabs (and I talked to them) were actually happy about getting rid of Saddam Hussein. There was no strong resistance because the Arabs didn’t want to fight. But then when special leaders, like Sadr, turned up, things got seriously hot. Those events occurred during our service in Iraq. Serious military operations started about two weeks before Easter. One of them was when the American troops were to take over the town of Faludja. They were not really large scale operations, but there was definitely lots of fighting involved…The locals’ attitude to us was interesting. They regarded us in a different way, not as they looked upon American troops. The Arabs liked talking to us better than to Americans. The memory of the powerful Soviet Union which used to support them is still alive, so they were really friendly towards us. Most of the civil population was really friendly.

– But you had to fight the same Arabs?

– You know, once I asked one of the more educated Arabs whether they considered us to be occupying forces. And interestingly, he said that they had done the same with that land many years ago. Arabs had come and conquered that land many centuries ago.

That Arab leads a patriot Muslim kind of life. At the same time, being an educated person, he is logical in his thoughts.

– Such attitude is probably rare in Iraq?

– As a rule, all sheiks, who are the heads of big family clans forming entire towns, are well-educated. And as a result their attitude towards us was relatively positive.

– As far as I understand, you were mostly communicating with the civil population and not with the Iraqi military or partisans?

– Quite the opposite. Since we were the peace-makers, we were supposed to set up new a social infrastructure, including state protection. Thus, we had to help them to restore their Armed Forces as well. We were not the only ones who helped them, all of the coalition forces were aimed at that. There was new recruitment, and new Armed Forces of Iraq were formed. They include police departments and armed national security squads. So there was lots of communication with Iraqi military and police.

– What, do you think, is the greatest danger for a soldier’s soul at war?

– The greatest danger is to seek religious motives in this war. You cannot do that. Bishop Augustine was correct to say in his speech at the Christmas Readings that this war is political. And an attempt to justify yourself in this war, morally or ethically, can mean running to opposite extremes, calling this war religious, supposedly Christian and directed against the Muslim world.

– What was your time with the soldiers like? What did you do specifically as a priest?

– As a priest…I would take a video with spiritual content (our synodal department provided me with such materials) and would go and watch it with the guys. It was their choice whether to go. About five people minimum would watch, some came, some went — they are all on active service, you understand. But after watching such a film a conversation about something spiritual usually would get going. People would start feeling easier, ask questions, and the talk could go on for a long time.

– Was it difficult for the soldiers to overcome various inner borders or complexes concerning faith?

– Absolutely not. Our Slavic people — Serbs, Bulgarians, Belarusians, Ukrainians and Russians, all of us have Orthodoxy in our veins, in our blood. So we adapt to religious things really easily. So easily, that in a month’s time a priest in the army wasn’t some kind of nonsense, but a most normal thing for them.

– Did they come up to you to ask questions and seek advice?

– Of course they did, like when you are going somewhere people would come up to you on the way. The attitude was generally very friendly. Soldiers would stand up to greet you, it is in our blood. There was no barbaric attitude to religion at all. Of course, it was always easier with religion in the Ukraine, especially in West Ukraine, where the Soviet power didn’t succeed much in killing faith in people’s souls. There never was much fierce atheistic resistance there, neither there was in East Ukraine.

– Well, maybe at war they were nice and friendly like that. But it is common that a man has no time to spare for God.

– Well, you can get used to the war as well. Sure you cannot get used to the idea of being killed: the guys go on a mission and don’t know whether they would be back. In our most critical moments it was interesting for me to watch the dynamics of the church-going. Normally some people call on us, some don’t. But whoever goes on a night patrol always calls on our tent church. People would come and go one by one. It is natural for a person, even if they were not brought up in Faith, to pray ‘Have mercy on me’ at critical moments, and when it all ends safely — "Glory to God". That could be all there is to their religiousness.

– Have you noticed, after coming home from war, any changes in yourself and your outlook on life? Have you felt any bitterness towards people who are not familiar with war?

– No, not at all. Attitude to oneself does change. A non-Christian can get bitter. A Christian believes in God’s plan for him. Bitterness against what? Against the fact that I had to be at war? I didn’t come up with such entertainment for myself. God put me in such circumstances, hoping for my personal growth. I am not expected to do much, just be patient.

– I mostly mean bitterness against the evil and violence which you witness at war. It must be very hard to go through it?

– I don’t think there is much less evil in our contemporary civil society. Here a man is killed bodily, there he is killed in his soul. Naturally, it is harder to witness the former, but how many people are killed spiritually here, in peacetime? Dead corpses are walking around. This fear of physical death, where does it come from? It comes from our imperfection. Holy Fathers could cry over the dead world. They cried more over this apparently successful society, than about some military operations. Here people die spiritually every hour, every second. They exist in their bodies without understanding why they exist at all. That’s why I must honestly say that I don’t think that any of the priests, any of the soldiers would get embittered over what they have seen or gone through. Each of us does his duty. People in such situations, being sent by their state, regard it as their duty. He is a soldier, fighting is the Army. He has to take part in it.

– But wars are often called senseless, being arenas of the careless politics of authorities. In Russia it is Chechnya, in the Ukraine — Iraq.

– Well I wouldn’t call it senseless, thinking from the heart. Iraq is another story, but I must say I don’t agree with such a position on Chechnya. Nothing can be senseless, and the proof is the aggression coming out of Chechnya, you take Beslan. The essence of the problem is like that: Chechnya is like an abscess. It can hurt. You can ignore it, but sooner or later it would explode and infect other areas. So it would be better to perform the surgery right now, remove it. This is my concrete opinion on Chechnya, because Beslan is the proof of their reaction. Iraq is a different matter. Of course we, being Russians, are ready to justify the war in Chechnya and not really justify the war in Iraq, because it’s not ours. But the essence certainly is the same — politics. Bishop Augustine was right when he said at the Christmas Readings that it is not a priest’s business to do politics, we must take care of our direct duties — spiritual tending to our flock.

– What was the biggest obstacle in your priestly service during your stay in Iraq?

– The absence of church-going. Man is always short on time. He usually has two options — either to go and pray, or go and have some decent sleep before going on a mission. There is a lot to do. And most often a soldier would choose to get himself together physically, than taking time to pray. And how do you really become a church-goer without going to church? Of course I could provide some spiritual guidance, relief, but bringing a man to serious spiritual work on himself is a real problem at war.

– And what was the biggest joy?

– When a man turns to the Church. When a warrior comes and says: "I’m fed up, Father, I don’t know how to live further. Help me," and then you see how he is attracted to spiritual life, starts going to church, reading spiritual literature, and then another man has become Orthodox. Coming back to your home city is a big joy as well.

– What was your most vivid memory of the seven months of stay in Iraq?

– There were lots of memorable events. It’s difficult to choose the brightest. The most intense feeling was fear. I remember it most. Not fear for myself, but for the people around you. You get so close in places like that. And it is so difficult to lose somebody in your life, when you know all about him — what he likes, what he loves, all about his family… And then you start fearing for all the people you know, people you are close to through this service, just for those live people. When you hear on the portable radio that "the battle is over, some injured, but no dead, thanks God."

And then you hear the name of your friend who you played chess with the day before, it is the most fearful moment…Or another time I lay down to have some rest after serving Divine Liturgy. I always served it really early so that the guys who were to leave for the day had time to call in. And I had a phone call, asking me to come to the headquarters. And then in the headquarters they told me that their captain had been killed on a landmine. That fear is the most realistic and most evil…

Certainly, there were some funny stories to tell. Once I convinced a captain to get baptized by telling him that it would be really meaningful for him to be baptized where civilisation had begun. Iraq is Babylon, where civilisation was born, and he would be born as a new man spiritually in the same place. He was so impressed by my arguments that he wished to be baptized there.

– Thank you, Father Josaf, for taking the time to answer our questions.

– Glory to God, as long as it serves people.

Hegumen Josaf (Peretiatko) was interviewed by the 5-year student of the Stretensky Theological Seminary Sergei Arkhipov