The film is very aptly named—this is truly a lesson, a warning. Anyone who was looking for a video illustration of a history textbook was no doubt disappointed; anyone who dreamed of finally hearing a truthful word on Byzantium, the cradle of our Orthodox civilization, was probably also disappointed—a film on the true history of the Byzantine Empire and its place in the development of world civilization still awaits its historical hour. We are in great need of such a documentary today—a detailed, concerned history of the fate of Byzantium and its inheritance. Fr. Tikhon’s work has made us feel this need even more acutely.

The authors’ intention was not to “rehabilitate Byzantium” or give a lecture, but to break through our routine perceptions and awaken our thoughts. They undoubtedly succeeded in their aim. The unusual historical fate of an Empire that existed on one-sixth of the inhabited world for nearly ten centuries is definitely instructive. Even more instructive to those who live in Russia at the beginning of the 21st century is the history of that Empire’s collapse.

Byzantium and the Crusaders.

“In the morning they went into the Hagia Sophia and opening the doors, they cut off the embolus made of silver, they tore off twelve silver columns and tore down four iconostases, and twelve holy tables and altar gates. They took together with the precious vessels the Gospels, crosses and icons, from the latter of which they tore off the rizas… Thus did they rob the Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Theotokos of Blachernae … this is not to speak of the other churches, for they are without number…” These sorrowful lines describe not the sacking of Constantinople by the Turks, but the entrance into the capital of Byzantium by Latin knights during the fourth crusade (F. I. Uspensky, The History of the Crusades). Holy relics, wealth, masterpieces of art, iconography, and craft were carried away from Byzantium to the West. We can now admire all of these riches in the museums of Venice and Paris, and in the cathedrals of European cities.

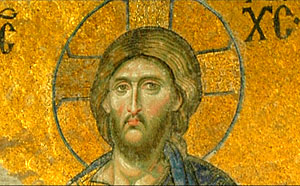

At first C. Diehl describes the wealth of Constantinople which met the eyes of the first crusaders. “The Crusader-pilgrims, writing their impressions in their naïve language, could not sufficiently express their amazement. The troubadours of the West spoke of Constantinople as a magical country, a golden dream; they described its incalculable wealth, its luxurious and noisy crowds, its sophisticated art, and its market where there were goods from all over the world, where ordinary passers-by ‘looked like the children of royalty.’ There were palaces, porticos, sparkling gold mosaics in the Churches…” Byzantium was truly a queen of elegance and beauty. The knights of the West knew only one occupation, and one entertainment—hunting and war—while Byzantine life was multi-faceted and refined. “Amidst this elegant society, at that court with its ceremony and rigorous respect of rank, the Western crusaders, filled with deep indignation for these Greek schismatics drowning in wealth, felt deeply wounded, and began to behave ‘like thieves and robbers.’” The Byzantines were horrified to the depths of their souls “and could not come to themselves.”

What gulf lay between the Eastern and Western Roman Empires? These were two different civilizations: Byzantium inherited the ancient arts, culture, laws, and perception of the world; but breathing new life into all this was Constantinople’s own inheritance—the true Orthodox Faith, to which it held more firmly than to all its amassed riches, more than to the Justinian Code. After all, when the Empire was no longer, only the Faith remained, only Orthodoxy was preserved on the periphery of the once unconquerable Byzantium.

Having suffered defeat in their battles to free Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the infidels, the Crusaders saw in Byzantium a prize no less significant, but much juicier. Already in the twelfth century, plans were drawn for a crusade against the Byzantines. “The spiritual leaders, the popes, thought only of this—that by taking advantage of the emperors’ difficulties and calamities they could get them to unite with Rome, and submit the Greek Church to the papacy. The Byzantines, opponents of the union of the Churches, were by no means mistaken when they said that, be it in the form of open enmity or under the guise of disinterested aide, the West was essentially after one aim: to destroy the cities, peoples, and names of the Greeks. And if … Western Christianity allowed Byzantium to fall in the fifteenth century and surrendered it to Turkish rule, the main reason for this must be sought in their long-standing antipathy, their deeply rooted antagonism, which made any agreement between the Greek East and the Roman West impossible. If the Christian world allowed the fall of Byzantium, it was because it hated the implacable enemy and deceitful schismatic which it saw in it, reproaching it doubly as the reason for its failure in the crusades, and because Byzantium always sincerely refused to enter the bosom of Catholicism.” Thus was the French scholar’s sentence upon the Latin world.

Certain viewers addressed this question to the filmmakers: “Why didn’t you show anything about the taking of Constantinople by the Turks?” But the fall of Byzantium was already predetermined long before 1453; it was predetermined by its conflict with the West. This is also one of the lessons.

The Byzantines believed that the political construct of the world is a part of the universal Divine plan, and closely tied to the history and salvation of mankind. Constantine had foreordained this people to serve Christ and bring the light of the Gospels to others. Pax Romana was to be equivalent to Pax Christiana. For those who look at history as the “river of time,” Byzantine fortresses, Venetian palaces, and the modern-day squares of Istanbul exist side-by-side. This is only our broken awareness, deprived of historic character, perceiving the world as divided amongst the shelves of a card catalogue. This is also how Archimandrite Tikhon moves around in history, taking us from the Hagia Sophia to the Cathedral of St. Mark, to snowy Russia.

The film’s main theme seems to us at once exceedingly timely and brave. Emperor Basil II, one of the more successful rulers who seemingly anticipated everything—a huge treasury (the stabilization fund), a military armed with “Greek fire,” and luxurious architecture in the capital—was unable to create a mechanism of succession to power, and all was lost in the wink of an eye! How often have [Russian] emigrant officials and historians lamented over the similarity of the fates of two Orthodox sovereignties… The historical parallels never seemed stretched or artificial to them; they only came too late.

The fall of the Byzantine Empire is the fall of a nation, but not the fall of the Byzantine inheritance. This is exactly what it we would like to discuss, thanks to Archimandrite Tikhon’s wonderful idea of turning our mental gaze toward the lessons of Byzantium.

Byzantine alliance of nations.

The concept of a Byzantine alliance of nations was introduced to scholarship by the remarkable British scholar, Dimitry Obolensky, a Russian by nationality. In speaking of the complexity and non-traditional character of the Byzantine approach to the problem of nationality, Fr. Tikhon was referring to this very phenomenon. The Empire was an organism more complex than the nation-state better known in the West.

This very ability to create a national and stable unity should interest us most of all. Historians know very well that the Byzantine Empire, especially during its height, was a state consisting of Greeks and Slavs. Perhaps this is why our hearts are not indifferent to the name of Byzantium. The Slavic inheritance also awaits its synthesizing research, but without an understanding of the fact that a discussion of “spiritually close” nations is not mere political speculation, but a historical truth, we will not be able to understand why we [Russians] are so anxious over the fate of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Kosovo, and Metochia…

Only this did not occur right away in Rus’, but rather through the southern Slavs, through the tradition of Cyril and Methodius, through the schools and monasteries of Southern Serbia and Macedonia, through the Ochrid episcopate, and the ascetical labors of Saints Nahum and Clement. The teachers of the Slavs, Cyril and Methodius, wrought the miracle of turning the Slavic language into a sacred language of the Divine Services, and thanks to this, the Gospels were successfully and wondrously preached in Rus’.

This meeting of the Byzantine and Slavic worlds became important to the fate of Orthodoxy as well, for it enabled the Faith to outlive the State! The creative impulse that came from the meeting of Byzantium with the Slavic world was embodied by the tradition of Cyril and Methodius. For, as we know, the language of the Liturgy becomes sacred, and the nation in whose language the Holy Scripture exists occupies a special, lawful place in the Christian World—it obtains an independent historical meaning! Orthodoxy received a new impulse for internal development thanks to a unique phenomenon—the establishment and existence of a monastic alliance on the Holy Mount of Athos. The hesychastic tradition which was born there during the 10th century became the crown of the Orthodox Faith, and even further united spiritually the various parts of the Byzantine alliance.

All of the above in no way idealizes the internal structure of the Byzantine Empire; relations between Greeks and Slavs were nonetheless uneven and alternated with wars and conflicts. The political ideal of “a symphony of powers,” harmonious, mutually acting spiritual and secular authorities, remained more an inaccessible height than an active reality, but it was Byzantium that gave us the gift of this concept, just as it gave us a developed system of law, legal procedure, and moral norms.

For all of our [Russian] rootedness in the ethical and aesthetical order of Byzantine life, we now too often perceive everything through the intermediate layers of other cultures and values. But the most important aspect of this culture remains practically unaltered from the time of Saints Constantine and Helen—the Orthodox Liturgical Services, the Sacrament of the Eucharist, that “symbolic drama of man’s salvation,” which is performed by the Orthodox people of Eastern Europe in the same way, in all the churches, up to this very day.