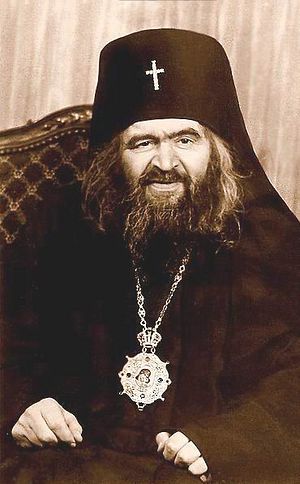

It is always pleasant to talk about the great saint of the twentieth century John (Maximovitch), especially because he occupies the most important place in my spiritual development. Unlike my matushka, who grew up in France near Vladyka John, I was never personally acquainted with him; but I firmly believe that St. John guided me throughout the course of my pastoral service, and led me to the priestly service in the church community that he founded in 1949 in Washington, D.C.—the Cathedral of St. John the Forerunner.

Researching the Life of this ascetic of faith, it is not hard to be convinced of the fact that this outstanding hierarch of the Russian Church was guided in all of his official decisions and personal acts by patristic ecclesiology.

The saint loved with intense fervency his native land, its history, and its sacred shrines. He was filled with profound anguish over Russia’s enslavement to antichristian forces and was completely irreconcilable with the godless government. Nevertheless, love for his earthly fatherland did not limit his archpastoral service to care only for his own people. He possessed a universal vision of the Church’s mission and was penetrated with the ardent desire to share the inheritance of Holy Orthodoxy with all. This conviction can be seen in many of his sermons and instructions.

“Besides the care for your flock,” said the saint as he sent off one young bishop to his forthcoming episcopal service, “you must also spread the Christian faith among those who have not yet come to know the Truth. The preaching of Christ’s teaching and faith in Christ and in the Life-creating Trinity is the fulfillment of the duty Christ commanded of His apostles, and it is the inalienable duty of archpastors and pastors…

“Following Saints Basil the Great and John Chrysostom, praying at the Diving Liturgy for the entire Church and for the whole world, the bishop should not only know his own region, but should also take to heart everything that happens in the whole Universal Church.”1

On the mission of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, Vladyka John wrote:

“The task of the Church Abroad is to prevent the dispersion of the children of the Orthodox Russian Church and to preserve the spiritual values they brought with them from the Motherland, as well as the spreading of Orthodoxy in the countries where they live.”2

It is no accident that St. John enjoys particular veneration among Orthodox Christians of various peoples, who perceive him as their own, dear saint.

St. John’s profound ecclesiasticism was formed not only thanks to his brilliant theological education, which he received at the theological department of Belgrade University, but was first and foremost the fruit of his mental prayer activity and daily celebration of the Liturgy.

St. John carried out his archpastoral service during a very complicated time for Christ’s Church. The Church in strangled Russia was enslaved, and the Russian refugees in the diaspora the spread across the entire planet were forced to organize themselves, to build their own personal and church lives in foreign lands and under very difficult conditions.

On June 10, 1934 in Belgrade, John Maximovitch was appointed bishop of Shanghai and made a vicar of the Peking diocese. The newly-consecrated hierarch arrived in Shanghai on December 4, 1934, where by that time 50,000 Russian refugees were living. Here he immediately set out to mend the serious rifts that had formed between the Orthodox parish communities and to unify his new flock.

In Shanghai under Bishop John new churches were built or finished, but his main service was aid to the needy, especially children. At his blessing and with his personal participation, in Shanghai were built hospitals, shelters, schools, homes for the aged, a public cafeteria, and vocational schools. He organized the St. Tikhon of Zadonsk shelter for orphans and children of poor parents. The saint himself gathered up the sick and starving children on the streets of Shanghai slums and brought them to the shelter. Vladyka gave much attention to religious education, visited prisons, and came to see the sick in hospitals and psychiatric wards.

During the years of the Second World War, the situation in Shanghai was extremely complicated. Russian emigrants were without citizenship, the Soviet diplomats conducted strong propaganda, persuaded Russians to return to their homeland where, as the diplomats portrayed it, a lawfully chosen patriarch headed the Church, churches are being opened, and all Russians would receive amnesty. In Shanghai around 10,000 Russians took Soviet passports. Many Russian bishops in China succumbed to Soviet propaganda, including the famous missionary to Kamchatka, Metropolitan Nestor (in 1948 Metropolitan Nestor returned to Russia, was arrested, and sent to the prison camps of Mordovia, where he remained until 1956).

The contact between the Synod Abroad and the Russian Orthodox diaspora in China were disrupted. In July of 1945, a bishops’ conference took place in Harbin, which resolved to ask Patriarch Alexy I to accept the diocese into the fold of the Moscow Patriarchate. One of the participants in this entry of the Orthodox Church of China into the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church was Bishop John. Vladyka John based his decision in the following way:

“After the Harbin diocese’s decision and in light of the lack of information on the Synod Abroad over a number of years, any other decision would have made our diocese a completely independent, autocephalous diocese. There are no canonical conditions for such independence, inasmuch as there is no doubt in the lawfulness of the elected Patriarch… Pronouncement of the name [at church services] of the Head of the Synod Abroad should for now be preserved, because according to rule 14 of the Double Local Council, it is forbidden to cease the commemoration of your Metropolitan by your own volition….”3

Archbishop John began commemorating the name of the new Patriarch and continued to commemorate Metropolitan Anastasy (Gribanovsky), the Head of the Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. But when normal relations with Synod Abroad were restored, and it was determined that the election of Patriarch Alexy I took place with violations of the canons, Vladyka John discontinued his commemoration of the Patriarch. Nevertheless, the saint continued to hope for the reunification of the Russian Church:

“Long yearning and working for a common goal and acting separately due to the conditions in which each of them find themselves, the Churches within Russia and abroad can more successfully achieve the fulfillment of both their common tasks as well as their individual tasks, until the opportunity for their complete reunification comes about.

“At the current time, the Church inside Russia should try to heal the wounds wrought upon it by militant atheism, and be freed from the bonds that obstruct the internal and external fullness of its activities…

“We pray to the Lord that He might hasten the onset of this desired and yearned for hour, when the First Hierarch of all Rus’, ascending his Patriarchal throne in the Dormition Cathedral of the capital city, gathers around himself all Russian archpastors, gathered from all Russian and foreign lands…”4

Vladyka reposed in 1966, without living to see the longed-for restoration of Eucharistic communion between the two branches of the Russian Orthodox Church.

In December 1965, a half year before his repose, St. John answered a question from the Synod of the Church Abroad concerning the desirableness of calling a Third All-Diaspora Council:

“With the regard to the calling of a Council that would include the participation of clergy and laity… I consider that such a Council is desirable and extremely necessary… (At it) the voice of the diaspora should loudly speak out against the continuation of persecutions against the faith; they need to express their sympathy and spiritual unity with our brothers and sister suffering there for the faith… It is desirable before and after this to make attempts to restore the unity of the Russian Church Abroad, and in any case, to preliminarily soften relationships with those parts that have broken away from Her.5

* * *

I was ordained a priest on September 1, 1974, a week before the commencement of the III All-Diaspora council of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. This was a time when there were no official relations between the Church Abroad and the Moscow Patriarchate. I could not then imagine that in thirty-some years the Lord would lead me to become a member of the pre-council commission and a delegate at the IV All-Diaspora Council, where the questions about the future of the Russian Church Abroad and the restoration of Eucharistic communion with the Moscow Patriarchate would be decided.

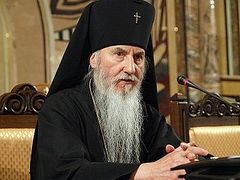

In May 2005, the First Hierarch of the ROCOR, Metropolitan Laurus, announced the convening of the IV All-Diaspora Council. During the course of the year, at the parishes, at diocesan meetings and pastoral conferences there were lively discussions, at which the most diverse opinions were expressed, including even demands to postpone the Council. Thank God that Metropolitan Laurus did not stray from his course. And when the time came to compose the list of delegates for the All-Diaspora Council, Vladyka Laurus himself saw to it that opponents of reunification be included, so that all points of view would be heard. Bu in the meantime, what insults the now blessedly-reposed First Hierarch had to endure!

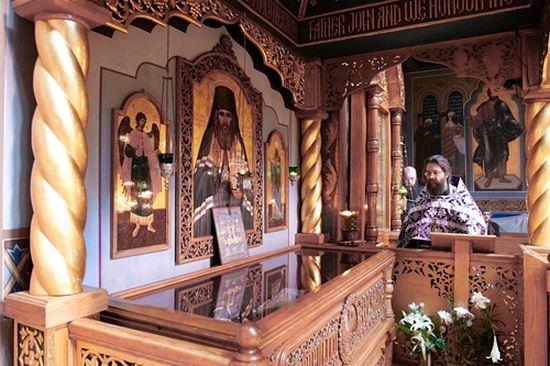

The choice of venue for the Council fell to the Holy Virgin Cathedral in San Francisco of the Joy of All Who Sorrow Icon, the construction of which Vladyka John had completed and where his honorable relics repose.

The IV All-Diaspora Council was convened on May 6, 2006. Throughout the working of the Council, the Hodigitria of the Russian diaspora—the Kursk Root icon of the Sign of the Most Pure Theotokos, which Vladyka John so revered and in Whose presence he passed into eternal life in 1966, was present.

Arguments over the question of coming closer to Moscow began in the lobbies, and officially from the second day of the Council. With each hour the discussions became more and more heated and opinions diverged: Many delegates talked about how the process of coming nearer is going too quickly, although almost no one argued with the principle of reunification itself.

There were many presentations at the Council, and over the course of a few hours, for me and many other delegates the original spirit of optimism was replaced by doubts that it would be possible to come to a unanimous consensus.

But during the stormy arguments and presentations by opponents of unification, I was attentively observing Metropolitan Laurus. Would he make a compromise with them? Archpriest Seraphim Gan, Metropolitan Laurus’s personal secretary, recalls:

“He was not afraid of them (the opponents of unity.—V. P.), but he loved them and considered it necessary to show his pastoral care for them; that is, to give them the opportunity not only to speak their minds, but also to receive all the answers to the questions troubling them. Here, again, he showed his faith in the fact that the matter of restoring unity is God’s will, all-good and saving. During one of the most stormy arguments … Bishop Ambrose (Kantakuzen), noticing how calm Vladyka Laurus was as he fingered the knots on his prayer rope and dispassionately presided over the meeting, said that the work of the Council is a sacramental action and therefore it is necessary to continue the discussion in a spirit of brotherly love and reverence—for at the Council, the work of God is done.”6

I distinctly remember how these emotionally uttered words of Vladyka Ambrose had a calming effect on those present…

By the end of the third day of the Council (May 10), the editorial committee headed by Archpriest Alexander Lebedev was directed to compose a resolution on the question of Eucharistic communion with the Moscow Patriarchate. Work on this document began in the late evening and proceeded very tensely.

By midnight the decision was made to interrupt the work and go into the cathedral, and to ask the God-pleaser St. John at his relics for his help.

A draft of the resolution was placed on the reliquary along with a list of the names of all the delegates of the Council. Fervent prayer gave us the assurance that all is being accomplished just as God would have it. After the moleben, work on the resolution went like a knife through butter and by the beginning of the plenary meeting on May 11, the resolution was ready.

The discussion of and voting for the Council’s resolution on the future relationship between the Church Abroad and the Church in Russia took place on Thursday, May 11. At the wise decision of His Eminence Metropolitan Laurus, each paragraph was voted on separately.

“When discussing the drafts of the resolution,” it written in the “Letter of the IV All-Diaspora Council to the God-loving flock,” “every paragraph was discussed and corrections entered, so that everyone participated in its creation. Truly, this was a conciliar creation, in which was tangibly manifested the grace of the Holy Spirit that had gathered us together. Every paragraph of the text was accepted by a separate vote—and accepted with marvelous unanimity.

“Many members of the Council later testified that they see as a miracle the conciliar unanimity of the joint work that they all suffered through.”7

Here are a few excerpts from the final text of the resolution of the IV All-Diaspora Council:

“We, the participants of the IV All-Diaspora Council, having gathered in the God-preserved city of San Francisco, in the blessed presence of the Protectress of the Russian Diaspora, the Kursk-Root Icon of the Mother of God, and the holy relics of Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco, in trembling recognition of the duty laid upon us, in obedience to our Archpastor, Christ, with complete trust and love of the pastors and laity to our First Hierarch, His Eminence Metropolitan Laurus, and the Council of Bishops, attest that as loyal children of the Holy Church, we shall submit to Divine will and obey the decisions of the forthcoming Council of Bishops.

“We archpastors, pastors and laymen, members of the IV All-Diaspora Council, unanimously express our resoluteness to heal the wounds of division within the Russian Church—between her parts in the Fatherland and abroad. Our Paschal joy is joined by the great hope that in the appropriate time, the unity of the Russian Church will be restored upon the foundation of the Truth of Christ, opening for us the possibility to serve together and to commune from one Chalice…

“Bowing down before the podvig [spiritual feats] of the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia, glorified both by the Russian Church Abroad and by the Russian Church in the Fatherland, we see within them the spiritual bridge which rises above the abyss of the lethal division in the Russian Church and makes possible the restoration of that unity which is desired by all.”8

Truly, the conclusion of the IV All-Diaspora Council was a real miracle of God’s mercy, which took place ten years ago before the unity of the Russian Church, for which the great holy hierarch of the twentieth century, Archbishop John the Wonderworker of Shanghai and San Francisco, so ardently yearned.