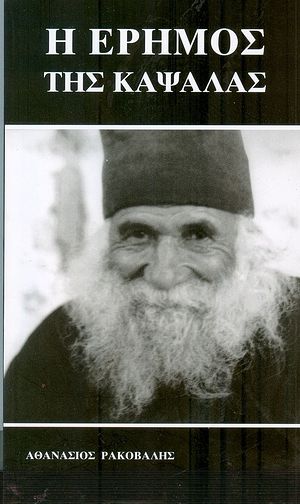

It was very difficult to get to his cell,1 even if you knew where it was. I lived in that area for several whole months and could not figure out the paths—they were so confusing, and there were so many of them. Once we went shopping at the store with a father who had taken me to himself. Along the way, I noticed some elder crawling out of the rubble.

“Father, who is that?” I asked my companion with amazement.

“Ah, him! It’s Geronda2 Herodion… from Romania… He’s a little crazy.

“Come on, let’s go see him. Maybe he needs something,” I suggested.

“Listen, it’s impossible to go see him—as soon as he sees someone, he immediately hides. He doesn’t want to talk with people. They say he’s out of his mind.”

“Fine, they know this area and the people better than me,” I thought.

Several months passed before I heard about Elder Herodion again. A new resident appeared in our area at that time—my peer, an Athenian with a mathematics degree, a young monk, completely inexperienced.

There is a rule on Athos: To live in solitude, a monk must be spiritually mature, he must have experience of spiritual warfare, and one other condition: He must be of a correct spiritual dispensation, otherwise there is great risk of falling into prelest or becoming bodily ill. First a monk must “be polished,” so to speak, for ten to fifteen years in a monastery, or with an elder in obedience, to learn the technique of warfare which the devil will carry out with us, and to learn mental prayer and ascesis of praxis, and then he can go to the desert. This is the general order on Athos, in the spirit of the Orthodox monastic tradition. The desert is not for all. The desert is for the spiritually advanced, for strong and experienced monks.

My friend spent only two years in a monastery, and after some very serious temptation, which nearly broke up the entire brotherhood, left for the desert. Of course, this was done without a blessing, going against the counsel of the elders, and even Elder Paisios himself.

Even I, being a totally “green,” inexperienced and unskilled Christian, understood all the danger of this and feared for him.

Fr. Hesychast, who received me to himself, often sent me to visit this monk, and we would try to help him with everything in our power. Thus, we became friends.

One young man from an Athens apartment came to the desert terrain of Kapsala on Athos. Not accustomed to working with his hands, having never seen a garden, he didn’t even have any idea how to plant an onion. Once he told me that Elder Herodion showed him some bread he had baked—it was harder than a brick.

“Listen, how did you bake this?” he asked.

“I mixed the flour with water and baked it in the oven!”

“Didn’t you add any salt or yeast?”

“What, did I need to add them?” he asked, laughing. They chuckled together.

My friend met Elder Herodion and took pity on him. He started bringing him “food.” I don’t know what kind of food it was, but I really doubt that the elder ate it, but sometimes he would bring him canned goods and bread from the store, and sugar, coffee, and salt.

But it wasn’t just that my friend took pity on Elder Herodion, but the elder himself took pity on the young monk. Therefore, he received him at any time. The elder would open the door of his cell to him and did not hide from him. The elder saw and understood the tenderness of his age, his spiritual inexperience, his bodily weakness, and the great danger in which he found himself.

Therefore, he opened not only the door of his cell to him, but the “door” of his heart. He began to preach wise spiritual counsel to him with various foolish acts3 and obscure statements.

Of course, the elder foresaw that within a few months he would change his cell and settle into a new one, next door to his elder. The cell was in very good condition, because the monk who had been living in it was a good proprietor and builder.

“Geronda, but some monk lives there,” my friend said, surprised.

“Don’t worry, he’s leaving here in the spring. He’s leaving the cell, and you will take it from the monastery with an homologie,”4 the elder told him—and so it happened, word for word.

This monk was a “zealot,”5 and he left the Holy Mountain in the spring, having spent twenty uninterrupted years in that very cell. He settled in some monastery in the world.

My friend and I were very impressed by what the elder had said.

“Indeed, he outsmarted us all!” my friend told me the next time I visited him.

“Who are you talking about?”

“About Elder Herodion… He’s laughing at all of us, feigning insanity, but in fact he’s a very spiritual man.”

“How do you know?”

The young monk started retelling me all the details of various events, and also the spiritual advice the elder had given him.

“Listen, let’s go see him sometime,” I asked him.

“Alright,” he agreed.

It was noon when we went to see the elder.

“Wait here, around the corner, so he doesn’t see you, otherwise he won’t open to you.”

I hid around the corner.

“Geronda, Geronda,” he called out. A few minutes later a small door opened, and the bent over Elder Herodion showed himself. They spoke a little, and the young monk beckoned me with a gesture.

“Elder, this is Athanasios, my friend.” Elder Herodion unexpectedly twitched, probably not knowing whether to hide or not, but in the end he stayed in the same spot, looked at me, and saying nothing to me, continued his conversation with my friend.

I was tormented by three questions at that time:

-

Why did God allow polygamy in the Old Testament?

-

How is it possible that such a Spirit-bearing, God-blessed prophet like David, who spoke with God, and who the Lord helped in all his difficulties, was overcome by carnal lust and fell with Bathsheba, and was married to several women?

-

How were these contradictions harmonized in that era?

I followed their conversation with surprise and found that Elder Herodion answered all my questions, even though I hadn’t managed to ask him. My friend didn’t even understand what they were talking about. I was bewildered; I looked at the elder with respect and delight.

At some point the monk turned to the elder and said, “Geronda, Athanasios wants to become a monk.”

“Oh, what kind of monk he would be! He is… a landlord—first in Thessaloniki, then he’ll live in a village near Thessaloniki, then Florina, then…” he paused—“Siberia, Siberia.”

My friend turned and said:

“Geronda, how did you know he’s from Florina?”

“What Florina? I didn’t say ‘Florina.’ I said ‘Florida,’ in America, where boats are moored”—and he began to tell us about how big the waves are there. We laughed about how skillfully he wriggled out of it.

Thirty years later, I see that practically everything the elder predicted came true:

-

I didn’t become a monk.

-

I lived in Thessaloniki for twenty-four years.

-

I’ve been living in a village near Thessaloniki for a few years already. What’s left? Florina and Siberia. I believe they will come true. I was amazed that not just my thoughts and the disposition of my heart were opened before the elder’s spiritual gaze, but even my future. “Wondrous is God in His saints.” Glory to God!

I was in a state of joy after this meeting, but at the same time, I was puzzled: O, what the Holy Mountain hides! What treasures! What spiritual treasures it offers!

Some monks considered Elder Herodion to be out of his mind. It was impossible to dissuade them. To decide this question for myself, I turned to Elder Paisios. As soon as I mentioned Elder Herodion, his eyes shone with joy, and his soul leapt.

“Geronda Herodion is a great ascetic,” Elder Paisios told me. “I sent Fr. Arsenios to him, but Geronda Herodion did not receive him. He sits in a corner of his cell, where the roof is still intact, and prays all night. He is a great ascetic.”

“Geronda, I heard that the Prot6 went to visit him, to see if he was really a great ascetic or just crazy.”

Elder Paisios laughed.

“Don’t’ worry, the elder will get through this.”

And truly, the Prot had taken my friend as a guide, and went into the Kapsala desert, to get to know this “unexplored mystery”…

This is what my friend told me about it:

“Elder Herodion drove him nuts; he gave him such a show that the Prot left him in a panic, a hundred percent sure that Elder Herodion is out of his mind. He had made his way to him along Kapsala forest trails in vain.”

Elder Herodion would reveal himself to young, weak, spiritual babes, but never to the curious who had no spiritual needs. We were spiritual babes then—weak, inexperienced, mournful—therefore he embraced us with his love and shared his spiritual riches with us.

Once my monk friend took another young father, who wanted to leave the monastery, to see him. He was tormented by numerous thoughts—the warfare was constant and very severe. It was winter—there was a ten-meter layer of snow on the ground, and low, heavy clouds in the sky.

Having heard him, the elder said:

“Thoughts are like clouds that hide the sun from us, that is, the grace of God. If you want to spiritually warm yourself, you have to make every effort to drive out the thoughts, otherwise you will cool off.”

“How can we drive them out, Geronda?”

“For God, it’s quite easy to expel them, but you have to work for it.”

The monk said nothing—it was obvious that he didn’t trust the elder.

“Do you want me to pray for your thoughts to disappear? Do you want me to pray for the Lord to disperse the clouds, so we can warm up a little in the sun?”

Again, the young monk said nothing. He was doubtful.

“Leave, clouds, leave,” the elder said, and the wind drove away the clouds, and rays of sun suddenly illuminated everyone standing there.

We were awestruck.

“Do you want me to wave my hand, and the earth will be covered with flowers?” the elder asked the young monk.

“No, Gerdona, that’s not necessary!” the monk worriedly exclaimed. He stood, thanked the elder, asked his prayers, and left the monastery, spiritually strengthened. His spiritual disposition had changed in a moment.

I really loved Elder Herodion. Every time I managed to get to Athos, I would ask about him and desired to meet with him, and the elder would receive me. Unfortunately, I only met with him a few times.

There comes a time when the aged very quickly lose their strength. Therefore, when the elder was completely exhausted, he allowed one Romanian monk to look after him. He took the elder to his cell in Lower Kapsala. This monk, as I ascertained, was not very conversant in the spiritual life. He was more a hard worker than a man of prayer. He worked very long and very hard. It seemed to me that the elder agreed to go live in his cell to help him spiritually. I don’t know, however, whether this monk spiritually fed from the elder or not. When I went to him and asked permission to visit the elder, he looked at me quite strangely. He probably thought I was also a little crazy. However, I was not the only one who showed such respect for the elder. For his cell attendant, it was quite incomprehensible.

Our last meeting went like this: At that time I was fascinated by Abba Dorotheos, who says in his writings: “Don’t cleave to anything; if your brother comes to you and asks for something, and you don’t know give it to him—you thereby prefer a perishable thing over love for your brother.” I really liked this saying, and I was trying to fulfill it in practice…

When I met with the elder, he asked me to give him something from my stuff, which I did joyfully. In the end, he asked me to give him my backpack, and he began sifting through it. This I couldn’t bear, and I snapped at him. There was a prayer rope in the backpack, given to me by Elder Paisios.

He turned the backpack inside-out and began to shake it out. “Oh,” I thought, “now he’s even going to take my prayer rope.” I was very upset about this. I thought, I couldn’t give away this prayer rope for anything in the world. Abba Dorotheos spoke precisely about this… The elder understood how I felt, looked at me, and stopped. He put everything back into the backpack and gave it to me.

How did he guess what I was thinking about, and that I was trying to fulfill the words of Abba Dorotheos? My soul was like an open book before him. He was like an ancient ascetic that we read about in the Paterikon.

Our mentor definitely possessed charisma—he was God-illumined… I can imagine what a number he did on this Romanian monk to spiritually awaken him.

A few years have already passed since I lived in Kapsala. My visits to the Holy Mountain became rare and short. One day I suddenly took a short trip to Athos. When I arrived at the cell where I always stayed, they told me that in an hour they would be having Elder Herodion’s funeral. Such unexpected news!... Of course I ran there.

Everyone who loved the elder was gathered at his funeral. Me from Thessaloniki, one from Athens, and another from the other end of Athos. We all found out about the elder’s repose “accidentally,” and we all gathered here “by coincidence.” The elder had gathered us all.

It’s difficult to call what happened a “funeral.” It was Pascha! A feast! A celebration! We all felt the joy.

I went to see Elder Paisios the next day and told him about everything. He carefully heard me out, agreed with everything, and “confirmed” everything with his word: “The gates of Paradise were opened to Elder Herodion!”

Something similar happened a few years later at the uncovering of the elder’s remains.7 Again we “accidentally” found ourselves at the uncovering of the elder’s remains. An atmosphere of joy and certainty that the elder abides in the heavenly mansions reigned at the transferal of his remains. His bones were the color of wax.8

Through the prayers of Elder Herodion, Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy upon us!

Elder Herodion was undoubtedly a great ascetic. His life was very severe: constant self-denial and self-humiliation. Simple human strength cannot accomplish this if the Spirit of the Lord does not inflame your heart.

Elder Herodion hid his great asceticism and his high spiritual condition under the cloak of foolishness.

If we could manage to remove this spiritual veil from the eyes of our mind, then we would clearly see one of the great ascetics before us.

The Lord took pity upon me in His providence, to thereby strengthen me in faith.

For others it happens differently, in accordance with the disposition of their heart. If God sees that we are grateful for small things, then He will give us yet greater things. God will never abandon us. He always gives us a chance—we just don’t want it. The problem is within us.

Why did God allow polygamy in the Old Testament?

How is it possible that such a Spirit-bearing, God-blessed prophet like David, who spoke with God, and who the Lord helped in all his difficulties, was overcome by carnal lust and fell with Bathsheba, and was married to several women?

How were these contradictions harmonized in that era?

I followed their conversation with surprise and found that Elder Herodion answered all my questions, even though I hadn’t managed to ask him.

========================================

Wonderful!

Would you mind to share that treasure with us too?

For the sake of abba Dorotheos.....