Sending the students of our Sretensky Seminary on summer vacation, we gave them an assignment: to meet with Christians two or three generations older than today’s youth and ask them about what was happening in the lives of those in a state which rebelled against God, and then tired of this rebellion, realized its futility and meaninglessness, about how they found and preserved their faith, and most importantly, what conclusions they arrived at as they approach the zenith or the sunset of their earthly journey.

I must say that all the students fulfilled this obedience with great benefit for themselves, and for us as well, their mentors and educators. All of their observations and notes, without exception, were extremely interesting. We would like to acquaint our readers with some of these works.

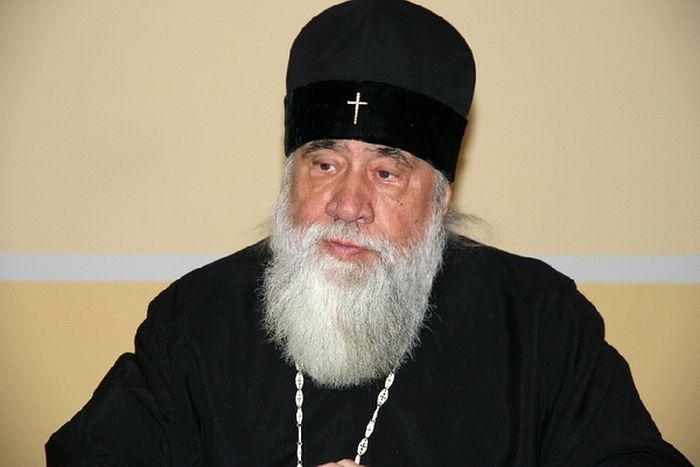

Bishop Tikhon,

Editor-in-Chief of Pravoslavie.ru

***

Metropolitan Jonah of Astrakhan and Kamyzyaksky (retired) dedicated his life to the service of God and His Holy Church from his youth. He was tonsured into monasticism at Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra in 1965, where Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) became his spiritual father. Met. Jonah spoke with Pravoslavie.ru about how people bore their faith through the years of persecution.

—If possible, begin with your childhood. Please tell us about your family, your parents, and your childhood and youth.

—I was born on June 13, 1941 in an Orthodox family in what was then still the village of Altufevo (now it is a region of Moscow). I was the fourth child in my family. Nine days later the Great Patriotic War began, and my father was called to the front. Mama especially fervently prayed for him, and perhaps by her prayers he returned from the front in 1945, alive and well. We lived modestly but very amicably in the village. We mainly lived on subsidiary farming. It was hard, but people bore it together, and it was felt. In 1948, I went to first grade in the Altufevo school. I studied well. I went to church from my early childhood. My first Pascha was when I was six—I still remember it. I would help the priest in the altar from that age. This is how I lived until I went to seminary.

—When you were studying in the Soviet school, did you hide your faith from those around you?

—I didn’t have any problems in confessing my faith until tenth grade, when my teacher was an avid communist, a teacher of history, whose lessons always bore a propagandistic character. He would always say, “The end of your Church is near.” They began to call me often to give an explanation to the director, but my classmates, especially the girls, stood up for me, and the teachers themselves stood up for me. I didn’t hide my faith, I continued to serve in the altar at our village church. Sometimes some of the teachers let me leave for the services before our classes ended.

—Did you and your family experience persecution in connection with your confession of faith?

—There were no clear persecutions. There was some harassment and ridicule, but nothing more…

—How were the churches and priests at that time?

—Churches everywhere began to close in the Khrushchev era. Religious propaganda was intensified. The persecution of priests began. I can’t say that every priest was so zealous at that time—there were all kinds. There were, of course, examples of true piety and asceticism. The churches were modest in adornment, but there was a special spirit—a spirit of unity in faith.

—How did the youth remain Christian in those years?

—There were many obstacles to confessing faith for the youth. For example, they prohibited people entering seminary after graduation from an institute, open believers were expelled from the same schools, they were deprived of work, and sometimes they were subjected to public scorn. They didn’t all endure: Some hid their faith, and some left it altogether.

—How did people celebrate the Orthodox feasts then—Nativity and Pascha?

—In my village, these feasts were celebrated by the whole world, although it was an atheistic time. We would go visit one another. The church, of course, could not accommodate everyone who wanted to come. During the procession on Pascha, stones and rotten eggs would come flying into the crowd of the faithful. The police didn’t let the youth into the church, but it was possible to go carefully. After the procession, the government representatives dispersed, and we served in peace. The whole church sang the Paschal Stichera. We went home singing “Christ is Risen.” We lived harmoniously… When I was already a monk of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra we also faced obstacles from the government on the feast of the Pascha of Christ: police barriers, government controls, and so on. I remember, our courageous hierodeacons would wave lit candles in these representatives’ faces lit when they were too aggressive.

—What were the lives of Orthodox Christians, and regular, Soviet people like?

—They lived modestly, but peacefully. They greatly valued human relationships and human warmth. It was the height of moral sense. I wouldn’t be exaggerating if I said that believers and non-believers differed only in the absence or presence of faith. Nearly everyone knew what was good and what was bad.

—Where did you get spiritual literature?

—It was all copied by hand… There were rare pre-revolutionary publications.

—Tell us about the ascetics of faith and spiritual people you communicated with.

—I especially remember Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov). They gave me to him on the day of my monastic tonsuring for spiritual guidance—he was a sensitive and spiritually experienced man of true Christian piety. I remember Archimandrite Tikhon (Argikov)…

—What holy places did people go to?

—We often went on foot from my village of Altufevo to the Lavra. Both young and old would go. I was particularly impressed. I then spent thirty-two years of my life there.

—How did Orthodox believers of the Soviet times differ from those now?

—There have been good and bad, weak and strong, zealous and negligent at all times, so I cannot identify any dramatic differences.

—What did they eat; how did they observe the fasts?

—They ate the same things as regular Soviet people. We upheld the fasts in our village, although, perhaps, not always strictly, but, for example, everyone honored Holy Week.

—What do you and your family remember about the Great Patriotic War?

—We remember the hardships, sorrows, and trepidation, but we continued to pray and did not lose faith. My father fought. He made it through the whole war… We kept the memory of the war by praying for the health and repose of those who fought.

—How did the people relate to what was happening in the country—to the creative, and to the negative?

—The internal and external policies suited nearly all citizens of the Soviet Union. The only thing is that believers mourned the lack of a possibility of openly confessing their faith, and the persecutions against the Church, and the closed churches.

—How were the relationships with parents and the elderly?

—The elderly were respected, we learned from them, and we tried to please them. It was manifested in daily life and in simple conversation. We gave up our spots to them in transportation; it was a shame to sit in the presence of the elderly. We were ashamed to smoke in front of them and to appear drunk.

—What is the most important thing you learned for yourself throughout the years?

—Faith in the providence of God… The most important thing in raising children is love and communication, well, and a little strictness; in relationships between people—love and understanding; in overcoming life’s troubles and misfortunes that befall men—prayer, going to the church of God, and communing more often.

—How should we relate to the negative things we find in the Church?

—Disorder and impure filth can be found everywhere. We have to try to let it pass by our hearts and not to judge, but to be attentive to ourselves.

And anyway, why should we, living in Russia, curse our state and our history?

What a disgrace to all of the martyrs, victims of the Soviet system!

Maybe ROCOR should officially rescind the 2007 reunion, now that it appears Sergianism is having a resurrection.