The regime ushered into Russia by Lenin and his minions had an overpowering destructive impetus—to tear down the old and build the new. They were most successful at tearing down the old, since any plans for the new were still rather vague. Besides the millions of human victims, their fury was particularly unleashed on church buildings. In some cases, respected archeologists and other scholars were able, through heroic efforts and ingenuity, to save certain famous church structures. But in most cases, the destroyers acted with such aggressive determination that there was no way to save even ancient monuments of Russian history. This was especially true in Moscow, which had once again become the nation’s capital city.

Sretensky Monastery was founded in 1397 to commemorate the deliverance of Moscow from the Mongols in 1395. In that year, word came to the citizens of Moscow that Tamerlane was advancing on their city. The Muscovites could only hope in divine intervention, and thus Metropolitan Cyprian, the first hierarch of the Russian Church, requested that the miraculous Vladimir icon of the Mother of God be brought from the city of Vladimir to Moscow. When after days of fasting, tears, and repentance the Metropolitan and his people met the icon just outside the city, the Mother of God saved Moscow from sure destruction by appearing to Tamerlane in a dream and threatening him.

The monastery grew, building-by-building, church-by-church, so that by the beginning of the twentieth century it had three main churches with a number of side altars—one of which was dedicated to the saint we commemorate today, Holy Hierarch Dimitry of Rostov.

The St. Nicholas Church, with its side altar dedicated to St. Dimitry of Rostov and an adjoining refectory, opened onto Bolshaya Lubyanka Street in Moscow. Until it was demolished in 1928, it was generally considered to have been built between 1679 and 1688 by donations from Boyarina Prozorovskaya over the place where the original wooden church dedicated to the Vladimir icon of the Mother of God stood. However, when the church was demolished, restorers discovered the remains of an ancient cupola “drum” and roofing, which were architectural fragments from the late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries.

The Church was built in cubic form on a basement. The altar of the church, instead of facing east according to tradition, faced north—this was because the Vladimir icon was brought from that direction in 1395, when the city was delivered from the invasion of Tamerlane and his Mongol hordes. The church retained its ancient architectural form until the twentieth century, with cruciform arches. It was rebuilt after the fire of 1737. The church also had a side altar dedicated to All Saints, built in the late eighteenth century, through donations from the head of Moscow, D. D. Meschaninov.

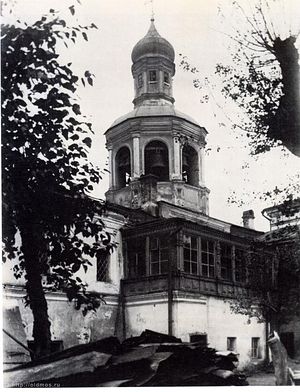

Next to the church stood the bell tower over the monastery gates, built in the 1670s. During the catastrophic Moscow fire of 1737 its upper part caved in, and in around 1740 it was restored.

The Sretensky bell tower was famous for it wonderful bells, which were selected for their harmony and elegant ringing. P. F. Gedike, the brother of the famous composer, said that at Sretensky Monastery, where he himself was a bell ringer and himself selected the bells, not a single bell could be removed without changing the sound considerably. When K. K. Saradjev, a well-known bell ringer, would “play” the bells for services at the monastery in the 1920s, crowds would gather on the corner to watch and listen.

The fate of the monastery’s bells was also interesting; they at least were not melted down as so many church bells were in those evil days. After the bell tower was demolished, the bells were sold in England, and as the historian V. F. Kozlov relates, they are still being rung in Oxford. There is also information that a portion of the Sretensky bells were sold in the 1920s to an engineer from the United States named Thomas Whitmor, for the price of scrap metal. He gifted them to Harvard University, where a special bell tower was built for them, and a society of amateur Russian bell ringers was even created in connection with them.

Sretensky Monastery functioned until 1926, although many of the monks had been arrested by the new atheistic regime. In 1922, the “church valuables” were requisitioned by the government. This included altar crosses, valuable Gospel and icon coverings, and silver reliquaries containing relic particles of St. Mary of Egypt and St. Michael of Tver. The fate of these miracle-working relics is still unknown. After the monastery was closed, the main cathedral functioned as a parish church, but even it was turned into a regional club in the 1930s, and then a dormitory for officers of the NKVD. During this terrible period, executions were carried out right on the monastery territory, and thousands of believers were shot, soaking the ground with their martyrs’ blood. Later the cathedral became a garage, and from 1958 until its return to the Church in 1991 it housed a restoration workshop.

In 1926, the Moskomunkhoz (municipal body governing the use of buildings) decided to tear down the St. Nicholas church with all its side altars, in order to enlarge Bolshaya Lubyanka Street. In 1928, it was decided to tear down the bell tower and refectory. Demolition began in July 1928, and soon other churches and structures of Sretensky Monastery where also destroyed. At that time, the very ancient Church of St. Mary of Egypt was also torn down—although it in no way hindered the enlargement of Bolshaya Lubyanka Street. That church, built in 1385, was also on the registers as a “first-class monument of ancient times”, and despite all pleas from the parish community and restoration specialists, it was demolished in 1930 with such rapidity that the specialists did not even have time to research its history. Reports written at the time state that it was taken apart brick by brick, and the bricks were given over “for municipal needs”. These ancient bricks, permeated with centuries of pious monastic prayer, were at best recycled to build the new soviet-realist architecture that would begin to blight the beautiful, ancient city of Moscow, and at worst, heaped up to form stables or public facilities.

There is no returning these monuments of Christian love and piety, but through God’s mercy, a new, magnificent cathedral now graces Sretensky Monastery. This church gathers together all of those who suffered through those unprecedented times of anti-Christian fury, who not only had to helplessly watch as their churches were being destroyed, but went to their own deaths at the hands of the modern-day invaders from within. These saints to which the new cathedral is dedicated are the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia, to whom we pray that God may deliver us from the evil one, now and forever.

Historical information from The Moscow We Lost, by Konstantin Mikhailov (Moscow: Yauz, Eksmo, 2010) (in Russian).