The Glinsk Hermitage was a provincial monastery at the beginning of the twentieth century, located in a desert wilderness, but its glory extended not only throughout the entire Russian Empire, but even far beyond its borders. The main peculiarity of its inhabitants was the inner spiritual activity which was later called “the phenomenon of eldership.” The monastery was closed after the revolution and all of its churches were destroyed. Now the territory is like one big construction site. Even the pilgrim’s hotel is being temporarily housed in construction trailers. However, despite the external inconveniences, you can still feel a special, unique spirit here, which attracts venerators of the Glinsk ascetics (the monastery has the relics of ten glorified elders).

We spoke with Archpriest Alexander Churochkin—a candidate in theology and regional specialist and the archivist of the Glink Hermitage—about how the monastery is being reborn.

God’s construction site

—Fr. Alexander, how long have you been studying the history of this monastery?

—I am a native of the city of Putivl. My ancestors are from here. Sophroniev Hermitage and Molchensky Monastery—all the sacred sites of this region—are also in my field of interests. Before entering seminary, I graduated from the historical department of the Sumy Pedagogical University. The topic of my doctoral dissertation is “The Putivl Lands: An Ecclesiastical-Archaeological Essay.” I am thirty-six, and I have probably been studying this since I was fifteen—so half of my life.

I was the full-time priest at the Glinsk Hermitage for several years. There was no fence here then or anything—just a group of buildings amidst the forest. Now, of course, the monastery has already regained some of its features. Life here is only improving, and Vladyka Anthony1 and the brothers are trying to revive the Athonite order, as it was before the revolution. They are gradually developing the territory and acquiring a farm to support themselves—after all, construction requires a lot of funds.

The Glinsk Hermitage had land holdings, a farm. For example, I found in the documents a note that a house church was built at the Negrovsk Farm. But what is this farm? It’s nowhere to be found now. There was a podvoriye in Glukhov and in Putivl, with mills, and a church. The monastery was very rich.

The ground here is sandy, thus the title “Glinsk Hermitage” is absolutely not because some potters extracted clay2 here, as it says in some books. There is no clay here, there is sand. The title comes from the name of one ancient princely family, from which came Elena Glinskaya, the mother of Ivan the Terrible. Their ancestor was a Tatar murza.3 He adopted Christianity, becoming Alexander in Baptism. He entered into the service of a Lithuanian prince and received the tiny Glinsk as an inheritance. Glinyak Creek was there (now a village of the Romny Region in the Sumy Province). This is where the Glinsky family name comes from. It’s about sixty miles from here.

These princes were viceroys of Putivl and they had the Glinsk apiary here, where one of the beekeepers found the Icon of the Nativity of the Mother of God of the Glinsk Hermitage, as it began to be called, after this tract of land.

—How was the Glinsk Hermitage revived? Was it a diocesan decision?

—When the hermitage was closed in 1922, these places were still part of the Kursk Governate. It was opened again in 1942 under German occupation. Then it was already the Sumy Diocese. In 1994, this place was on the territory of the newly-formed Konotop Diocese, which raised the question of returning two monasteries to the Church—Sts. Peter and Paul and Glinsk Hermitage. Both monasteries had housing for mentally ill women at that time. In response, it was suggested to pick one of them. The diocesan council chose Glinsk Hermitage. All the patients were transferred to Sts. Peter and Paul Monastery, and from 1994 to 1997, Glinsk Hermitage was under the jurisdiction of the Konotop Diocese, and then became stravropegial.4

—How did the decision to make it stavropegial come about?

—At one time, a boy named Vanya Kugimov lived in Novaya Sloboda village, where I serve now. In the summer, on July 7, 1942, he was taking the cows out to pasture in the meadow, and while he was out, his village was burned down, and his parents were killed. It was a terrible tragedy: The Magyar butchers slaughtered 586 peaceful civilians in two hours—the elderly, women, and children. They spared no one. This Vanya was left an orphan. He had an aunt—a nun. She took him to Glinsk Hermitage where he was later tonsured into monasticism with the name Leonty. Then they sent him to study at the Odessa seminary. Later he graduated from the Moscow Theological Academy and became metropolitan. In due course, he headed the Crimea, Kherson, Kharkiv, and even the Berlin cathedras. Metropolitan Leonty was very friendly with Metropolitan Vladimir (then the bishop of Chernigov), who later became the primate of the Ukrainian Church. He later wrote that “Vladyka Leonty was dear to my heart. We met and went to the closed Glinsk Hermitage together, where the memory of the Glinsk elders was alive.” Thus emerged His Beatitude Metropolitan Vladimir’s reverent relation to the Glinsk Hermitage and its elders. Therefore, considering the monastery’s important place in history, he gave it stavropegial status.

—How many monks are there in the monastery today?

—Including novices, there are twenty laboring here altogether. Our daily routine is like on Mt. Athos. Vespers is served at 8:00 PM, then the brothers go to trapeza, then Compline is read in church. Then they ring the bell—it means that walking around the monastery is prohibited, as well as conversation—the time of silence begins. The monks read their prayer rule in their cells and prepare for sleep. Then they get up early in the morning. Midnight Office, Matins, Hours, and Divine Liturgy are served around 4:00 AM. After Liturgy is trapeza, and then the monks go to their obediences. Then, around 2:00 PM is rest, after which Vespers is served again. This is the rhythm observed in the monastery now, like on Mt. Athos. This precise daily order is followed in Vatopedi Monastery in particular.

—Where do the monks here come from?

—Mainly from Ukraine. Five are from Kharkiv, and also from Krivoy Rog and Nikolaev. There are some from Belarus. But we shouldn’t ask a monk about who he was in his former life. People come here to change their lives and to serve God. The previous life of a monk is something hidden.

—What buildings remain today from pre-revolutionary times?

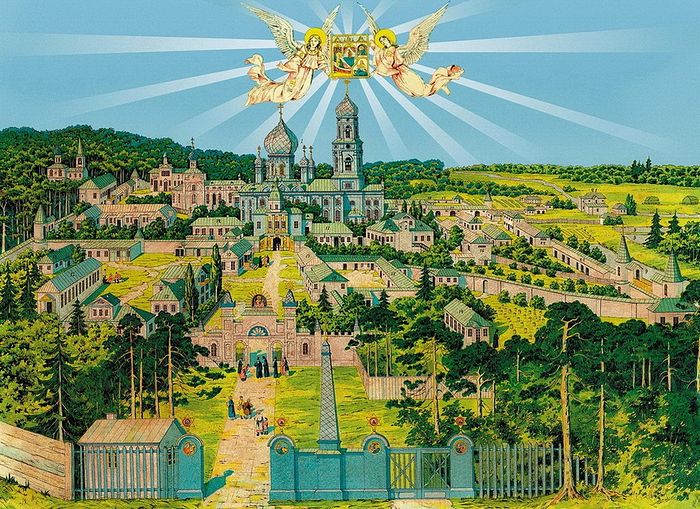

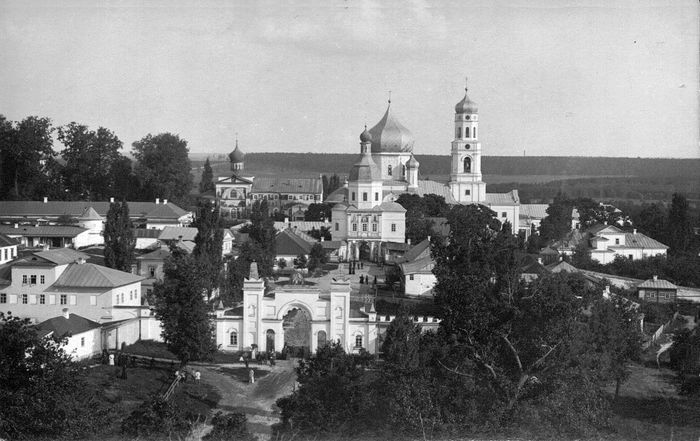

—At the time when Glinsk Hermitage was closed in September 1922, it was an entire city. If you look at lithographs with views of the monastery, you can see there were many buildings. But already by the end of the 1920s, all the churches except for one were destroyed (there had been four—three stone, and one wooden). Now, out of the pre-revolutionary buildings, you can see here only the trapeza, with a redbrick farmhouse next to it, the brothers’ dormitory, and the archbishop’s residence. There are fragments of the fencing here and there.

When I first came here, I was struck by the look of the Church of the Elevation of the Holy Cross. It was wooden, with a long dormitory adjoined to it, where there were cells. There were 700 monks here before the revolution, including the elderly. These people gave their entire lives, health, and youthfulness to the monastery, and the monastery took care of them to the end of their days. They were housed in a special hospital building where a house church was built. When monks came here again in 1942, they revived the liturgical life, and adorned everything magnificently. But the monastery was closed again in 1961 and given to be used for a home for the handicapped. They immediately built a bathroom in the altar. When I first saw this church, it was swollen, and the wood was rotten—that is, it had turned to ruins, to shambles. If it had been made of stone, then they probably would have tried to rebuild it. But the wooden structure was dilapidated and simply had to be dismantled.

—There is some intense construction going on in the monastery right now. Is there a general plan of action?

—Insofar as we don’t have any serious funding for the construction right now, it’s hard to plan it. After all, this is the outskirts, it’s provincial, and if many used to come here, then now there are very few groups of pilgrims. Our roads are very bad too. Those who were heading to Kiev from Russia used to go through the Katerinovka checkpoint, and they would often stop here. Now it’s very difficult, and secular people will not see any kind of architectural ensemble here, as they say, “to touch antiquity.” This place, consecrated and prayerful thanks to the saints, exudes antiquity. So, tourists don’t come here, but mainly just pilgrims who want to pray and thirst for spiritual solace.

—Is it being restored according to the old layout?

—The blueprints and documents of the old buildings were not saved, and only general photographs were taken. For example, the Iveron Church is now a gate church, although it was historically built by St. Philaret5 on a completely different spot. The St. Nicholas Church is on the foundation of the ruined Dormition Church. At the time of its destruction, the monastery consisted of a group of buildings from various time periods. They were built, dilapidated, and rebuilt—just like when people are alive they don’t always wear the same clothes. If you took at all the notable monasteries, their histories are histories of constant construction. But here, at the time of its rebirth, nothing had been held onto except for the place itself. Therefore, the construction here is being carried with a view to the best traditions, as far as is possible, of ancient Russian architecture and the Orthodox canons. Instead of planning, they’re just relying on the mercy of God: As the Lord governs, so it will be.

—From what sources are you gathering information on the history of the monastery?

—When the monastery was closed in 1922, they started a fire here. They burned icons, books—everything was destroyed. There is a description of the Glinsk Hermitage archive—pre-revolutionary, but practically nothing from it survived. People in the surrounding villages still have books with stamps of Glinsk Hermitage, so the archival search is not yet completed.

Glinsk Hermitage is lucky that Schema-Archimandrite John (Maslov) was a monk here: He wrote the fundamental work Glinsk Hermitage: The History of the Monastery and Its Spiritual-Educational Activities in the XIV-XX Centuries. It is a truly colossal work, with a Glinsk paterikon in three volumes appended to it. But the archives of Glinsk Hermitage are currently spread out across various regions, since the modern-day Sumy Province is an artificial region: part of the Kursk, Chernigov, Kharkiv, and Poltava Governates. It was established in this form in 1939. The Sumy archives preserve the service records of the monks of the twentieth century. There are also documents of the period from the second opening in 1942 until 1961—for example, the correspondence of the commissioner for the affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church, which contain detailed accounts of the condition of the monastery.

Of course, Fr. John (Maslov) published a lot in his book, but he died in 1991—that is, still in the Soviet era. There are some things he couldn’t write about then, because it was difficult times. He realized it wouldn’t pass the censor, so he took a lot with him to the grave. Several documents of the Ukrainian Security Service that had been classified are now declassified, and we have managed to find what Fr. John (Maslov) didn’t write.

—And what did you manage to find?

—Here, it would seem, a trifle: The patronymic of the last abbot (before the destruction of the monastery in 1922), Archimandrite Nektary (Nuzhdin), was unknown. Fr. John (Maslov) writes that he was Nikolai in the world. I managed to find documents at the Ukrainian Security Service where his entire name is given—Nikolai Flegontovich Nuzhdin. He talks about himself in them—what kind of family he was from, and how he arrived at the monastery. So, we are gathering material, and God-willing, we will reprint the augmented works of Fr. John.

“Having attained the love of Christ”

—How did the glorification of the Glinsk elders come about?

—First of all, we painted icons and acquired their relics. I also had to participate: With the blessing of Vladyka Luke (Kovalenko),6 I wrote the text of the service of the Glinsk elders. At the time, Svyatogorsk Lavra glorified those God-pleasers who had a relationship with Glinsk Hermitage, and also glorified Archimandrite Makary (Glukharev), the enlightener of Altai, who was tonsured here, and the question arose about canonizing the venerable Glinsk ascetics.

The relics of St. Seraphim (Amelin) were acquired immediately after the opening of the monastery. Until his glorification, they were venerated in a reliquary in the church. A lot of work was done then. Imagine what it is to acquire relics, and to do everything so that there are no mistakes. Archaeologists came especially for it, they all examined them, and looked at the descriptions. For example, St. Iliodor (Golovanitsky) was sick for a long time, lying in bed, and there is an historical description of this. Upon acquiring his relics, it was obvious how his vertebrae had fused: The condition of the remains testified that it was him.

There was an abbot Schema-Archimandrite Joannicius (Gomolko) of Glinsk Hermitage, Isaiah before the schema. He was a true ascetic, elder, and holy man. In the pre-revolutionary years, after the first Russian revolution, censorship was weakened, and material of questionable content began to appear in the press. For example, “Black One Hundred in the Province”—so the article of one landlord was called, who had a lawsuit against the monastery. Fr. Joannicius was slandered in this publication. Archbishop Stephen of Kursk, who was distinguished by his strict character, heard the slander. He ordered Fr. Joannicius to leave the monastery within twenty-four hours. He was innocent, and showed it by the following miracle: When the elder left the monastery, there was a springtime flood (earlier, before the swamp dried up, the river would greatly overflow). He left, and there was water all around. Fr. Joannicius blessed the water, and, in front of everyone, he left the monastery walking on it as if on dry ground. Fr. John (Maslov) writes about it in the Glinsk paterikon, and many here tell about it. I wondered where he disappeared to when he left. He didn’t drown, after all! Then, just before his canonization, I managed to find out there is a babushka living in one village who told about how before the revolution, her family housed a Glinsk batushka. Everyone was saying he walked on water. “I don’t know how it happened,” she confessed, “I wasn’t even born yet, but I heard that he walked on water. We were poor, but mama persuaded papa to take him in. Our lodge was small. We made a partition, and he lived behind it. He died at our place. He was buried in our cemetery. By his prayers, our entire family has been blessed by God. Everything is well-arranged for us. There are no drug addicts or drunks. Everyone is pious; everyone has strong families. During the famine we had food, they didn’t kick us out, and no one died during the war. And we always knew that it was the prayer of this batushka, Fr. Joannicius.” His relics have been found and are venerated at Glinsk Hermitage.

I specially went to the archives and looked at the documents, so there would be no doubt that it was precisely Fr. Joannicius. There was only one young monk with that name, but he did not at all fit the description. I looked at the Kursk list of monks—nothing matched. Only one matched—the abbot Fr. Joannicius (Gomolko). A year before his canonization, his relics were obtained and they repose now in the monastery. This is how the Heavenly Queen arranged it.

The first and second canonizations of the Glinsk elders took place on the spot of the destroyed Cathedral of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos. Both services were led by His Beatitude Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev and All Ukraine. The first group of holy elders was glorified in 2008. They were the ascetics who lived here before the revolution, and also Schema-Archimandrite Seraphim (Amelin)—the abbot of the hermitage at the time of its second opening (in 1942). Of the thirty newly-glorified elders, the relics of ten were acquired then. Eight of them are located at Glinsk Hermitage. The rite of glorification for three more God-pleasers was held then in 2010—Schema-Metropolitan Seraphim (Mazhugi), Schema-Archimandrite Andronik (Lukasha), and Schema-Archimandrite Seraphim (Romantsov).

—After acquiring the relics, and after the glorification of the elders, do you feel their prayerful protection and support? How so?

—Of course it is felt. They walked on every patch of ground, their prayers are felt everywhere. For example, St. Seraphim (Amelin) was already old and infirm and unable to move, and then one day, during obediences in the trapeza, the monks stood up and bowed. The novices were struck: “What was that?” And they answered them: “The abbot passed by.” Thus, the elder, being in a weak body, visited all the monastery obediences in soul, and the monks were given to see it. Therefore, they continue to abide here in soul. With their bodies they lie in reliquaries in the church, but they are also here in their souls. People come here and report of healings, of the graceful help of the elders, because they are clearly here. We are all humans, we want to see with our eyes and touch with our hands. That is why we openly venerate relics.

Athonite traditions

—The Athonite order is being revived in Glinsk Hermitage today, according to the ancient model. How much does it differ from the order of other monasteries?

—At first it was important to revive monastic life, and so we celebrated the services according to the order in parishes, only we added Compline and Midnight Office, and the services were celebrated daily. Now the liturgical rhythm is like during the second opening of the monastery, but there is a desire and aspiration to revive the pre-revolutionary order of Glinsk Hermitage. I managed to find a manuscript of St. Philaret himself in St. Petersburg. We took a copy of it and studied this document, but there was much we didn’t understand. However, when we went to Athos, we saw that everything is precisely observed there still. All these little things—at trapeza, how the brothers assemble at the services, and the routine. We hope this order will be revived here in full measure.

—Why was this order used in Glinsk Hermitage?

—It’s connected with the name of St. Theodosius of Molochansk. He lived in the eighteenth century—an extremely unfavorable time for the Russian Orthodox Church. The reforms of Peter I and the secularization of Church properties led to the closing of monasteries. Monks were considered parasites and were transferred to other work. They tonsured only the crippled and the elderly.

However, in Moldavia and Wallachia, which were then under the authority of the Turks, conditions were more favorable. Monasteries there, maintaining a close connection with Mt. Athos, were famous for their high level of monastic life and the names of their elders. The native of the city of Glukhov, Theodosius (in the world Theodore Maslov) went there, where he later became the abbot of Tismana Monastery. Then Fr. Theodosius and the brothers moved here, to Sophroniev Hermitage, and brought the Athonite order from there. He tonsured the future St. Philaret (in the world Thomas Danilevsky).

St. Philaret had been the ustavschik7 at Sophroniev Hermitage since he was sixteen, and he knew the Athonite order inside and out. When the brethren of Glinsk Hermitage chose him as their abbot, he brought with him the traditions of his monastery. Although the eldership in Sophroniev Hermtiage would soon fade away, it flowered in Glinsk and was transmitted to twelve other monasteries in the Russian Empire.

Eldership includes the practice of revelation of thoughts, when every monk or novice is entrusted to a spiritually experienced elder monk, who knows the fine details of the monastery order and the methods of fighting with sin. Every evening he receives the revelation of thoughts and teaches his novices. In this way, the bearer of this tradition, having spent the majority of his life in a monastery, purifies his heart and thoughts, and forms a special mentality. He also observes their habits and discourses about them. This is what he teaches his disciple. Time passes, and the disciple also becomes such an elder. In the twentieth century, the tradition of eldership was interrupted. In its most authentic sense, it was preserved only on Mt. Athos.

Our society has changed a lot. If before, for example, St. Seraphim of Sarov went into reclusion, then no one knew or saw. Now the world encroaches upon everything. But in Glinsk Hermitage, the monks have no personal money or cell phones. There is a computer only in the deputy abbot Bishop Anthony’s building, which is used moreso like a typewriter for important papers and orders because there is no internet in the monastery. Only the steward Fr. Gabriel has a telephone, because he needs it for his obedience. All of the brothers’ needs are provided for by the monastery.

—Is it possible to restore the tradition of eldership today?

—It is very difficult. Even in the Pskov Caves Monastery, which was never closed during Soviet times, the elders faded away. It’s not necessary that the elder should have a gray beard down to his knees. Fr. John (Maslov), for example, was not a decrepit old man, but he was considered an elder. An elder can be a simple monk.

Now we see among us elder mania, but it’s all imaginary. People look for elders in order to shift responsibility for their actions onto them: They look for those who would bless them to do as they wish. They go to an elder and ask his blessing for whatever they want. And when the elder blesses them for something different, they go to another, and another, and another, until they receive an affirmative answer to their request. This is actually spiritual infantilism.

When I was on Mt. Athos, they suggested that I go see an elder, but I was afraid to go see him. I know my sins; but to learn how I should live, I have the Gospel and the commandments. What else do I need? It is a monk who cuts off his own will, who should be led by the advice of elders; but we in the world have not given such a vow. We have families, we have work; we have to be able to make decisions and bear responsibility for them.

You often see today an elderly monk surrounded by crowds of admirers, hanging on his every word. If we ask God, then He will reveal His will to us—and not necessarily through an elder. Of course, a spiritual guide is necessary, but such a zealous quest for an elder is the wrong path. Someone doesn’t pray, doesn’t read the word of God, because he has no time; he doesn’t read the Psalter, but he wants all the answers to come to him immediately! Life is a constant battle, but we want it easy, like instant coffee.