The life of Olga Alexandrovna Romanov, the last Grand Duchess of Russia, was filled with such numerous sorrows as rarely befall a person in a lifetime. But through her kindness, modesty and courage she withstood all the miseries that lay in store for her in the twentieth century. In the early centuries of Christianity, even pagans admired the virtues of Christian women. Likewise, Grand Duchess Olga, unshakable and radiant, can be a source of inspiration and consolation to modern people as well. She was the benefactress of a large number of schools, hospitals, courses, almshouses, and charitable societies, and during the First World War she was a simple army nurse.

Even today her name is not forgotten—on November 4, 2017, a plaque to the grand duchess was installed on the facade of the building housing the Olginskaya Gymnasium (classical school, grammar school) in the town of Pavlovsk in the Voronezh region, as this educational institution was under Olga’s patronage. It was decided to name this gymnasium “Olginskaya” [“Olga’s”] in 1913, when the 300th anniversary of the rule of the Romanov Dynasty was celebrated. “On February 4, 1913, after the Minister of Education’s humble report, His Majesty the Emperor permitted the Girls’ School in Pavlovsk in the Province of Voronezh to be named after Olga, to be under the protection of Her Imperial Highness Olga Alexandrovna,” a document from The Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire reads.

But that is not all that linked Olga Alexandrovna to the Voronezh region (then a province)—it was there that she had her Olgino Estate, where she learned basic medical treatment. Thus the perpetuation of the grand duchess’ memory became a significant event not only in the town’s life, but also for the whole Voronezh region. Deputy Chairman of the Government of the Voronezh Region Viktor Logvinov, heads of administrations of the region’s municipal districts, directors of agricultural enterprises, church parishioners, residents of the town and the region’s villages were present at the unveiling ceremony.

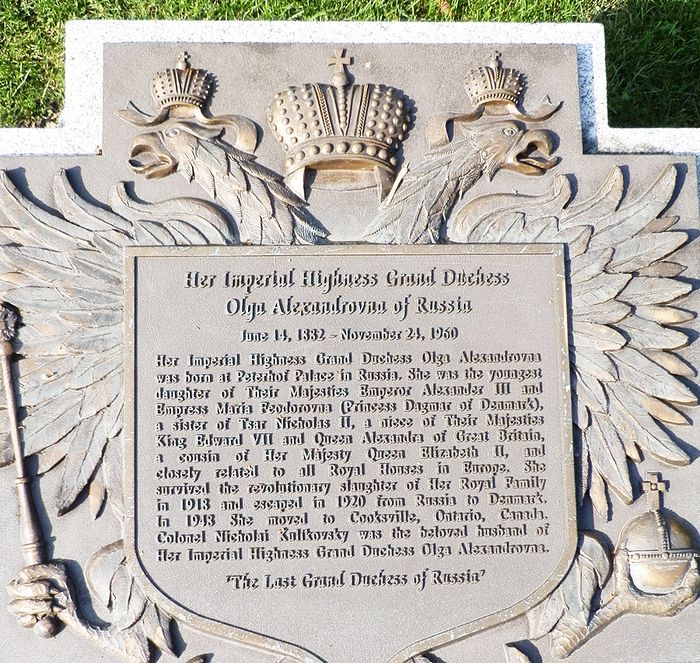

A memorial plaque installed on the exterior of the building of Olginskaya Gymnasium in Pavlovsk in honor of Grand Duchess Olga. Unveiled November 4, 2017.

A memorial plaque installed on the exterior of the building of Olginskaya Gymnasium in Pavlovsk in honor of Grand Duchess Olga. Unveiled November 4, 2017. On that day a solemn service was celebrated at the Church of the Kazan icon of the Mother of God in Pavlovsk. The Divine Liturgy was headed by Metropolitan Sergius of Voronezh and Liski with Bishop Andrew of Rossosh and Ostrogozhsk, Bishop Sergius of Borisoglebsk and Buturlinovka, along with numerous clergy concelebrating.

The Gymnasium students also prepared a photo exhibition for the honored guests dedicated to “the last Grand Duchess of Imperial Russia” [as Olga Alexandrovna was widely called towards the end of her life and afterwards.—Trans.], which was followed by another photo exhibition called “The Romanovs: the Royal Ministry” at the “Sovremennik” city community center.

The personality

Olga Alexandrovna Romanov (June 1/13, 1882 – November 24, 1960) was the youngest daughter of Emperor Alexander III and Empress Consort Maria Feodorovna.

The duchess had warm memories of her childhood. According to her own reminiscences, her parents had a happy marriage and their family was always very close. Much credit for this was due to Emperor Alexander III himself; despite his utter devotion to state duties (Tsar Alexander was commonly called “the busiest man in Russia”) he tried to spend as much time as possible with his children and was even involved in their games and pranks.

The upbringing played an important role in the formation of the duchess’ temperament, which can be characterized by her openness, honesty and strong will. The royal children, despite widespread opinion, lived modestly. They would sleep on camp beds with horsehair mattresses, placing thin pillows under their heads; an inexpensive carpet lay on the floor; there were neither armchairs nor sofas; the nursery’s sole decoration was its “Holy corner” (also known as “God’s corner” or “Red corner” in Russia) with icons of the Most Holy Virgin and the Savior strewn with pearls and other precious stones. Their diet was frugal; they would have porridge for breakfast, which was followed by a cold bath and a lot of fresh air. The children’s upbringing was based on the Orthodox faith. As Grand Duchess Olga herself later related: “All of us were raised in an atmosphere of strict obedience to religious canons. The Liturgy was celebrated every week, and numerous fasts and events of national importance were marked by solemn prayer services. All of this was as natural for us as the air we breathed.”

Olga Alexandrovna inherited her disposition from her father whom she loved dearly, namely her simplicity of taste, straightforwardness and ingenuousness. She didn’t like the luxury of the court; she preferred a linen dress to luxurious costumes and finery (which she jokingly called “armor”) at festivities. From her childhood she liked to talk with common folk, remembered the names of all the servants even in her old age, and regarded them as her family friends (in her later years, living in emigration, she became caregiver for an aged servant of her mother and refused to put her in a nursing home). Olga used to talk about the friendship she developed with peasants at her estate: “I saw their kindness, generosity and invincible faith in God. As far as I can judge, these peasants were rich despite their poverty, and when I was in their company I felt like a real person.”

Her failed marriage with Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg was a sad blow for the young Olga Alexandrovna. Obedient to her mother and unwilling to leave Russia, at the age of nineteen the princess married a man of very dubious reputation. Olga herself believed that the motive behind her mother’s decision was her (Empress Maria Feodorovna’s) friendship with the duke’s mother. Over the fifteen years of their family life, their marriage was never consummated—Peter Alexandrovich spent all his time at the card table, losing the emperor’s sister’s money at gambling. In 1916, Tsar Nicholas II approved the decree of the Most Holy Governing Synod that recognized his sister’s marriage with the Duke of Oldenburg as invalid. Olga Alexandrovna remarried and her second husband was Nicholas Alexandrovich Kulikovsky, an officer of Blue Cuirassier Regiment of the Imperial Cavalry. They had two sons together.

The faith and high morals fostered and instilled in the family helped Olga Alexandrovna endure personal and national tragedies—the 1888 Russian Imperial train disaster, when Alexander III and all his family narrowly escaped with their lives, the untimely death of her beloved father and elder brother George, and the wars and revolutions that ultimately led to separation from her beloved motherland. The fall of the monarchy was a calamity for the Imperial Family—twenty-seven of its members were killed, while all the others were forced to leave their native land. The most frightening pages of Olga Alexandrovna’s memoirs are devoted to her flight from revolutionary Russia together with her husband and mother. Their safety was not guarded, so they were within a hair’s breadth of destruction on several occasions. They actually had been sentenced to death during their stay in the Crimea, but the execution did not take place only because of the general turmoil. Fleeing from their persecutors with little children in their arms, they were starving and had no roof over their heads. They were not aware of the fate of other family members for a long time. After her mother’s departure, Grand Duchess Olga remained in Russia for some time on the territories occupied by General Denikin, unwilling to forsake the fatherland. She and her husband resided in a stanitsa [a Cossack village] like simple peasants. But with the arrival of the Bolsheviks who sought to massacre all the Royals, they had to flee. Rostov-on-the-Don, Constantinople, Belgrade, Vienna and, lastly, Denmark—this was their long path. Olga Alexandrovna always hoped to return to her homeland, but this never happened.

Relations with Nicholas II’s family

The grand duchess’ father, Emperor Alexander III, died when Olga Alexandrovna was a teenager. Her upbringing continued under her brother, Tsar Nicholas II. She wrote very affectionately of the tsar-martyr: “He was kind and generous to all whom he happened to meet. I have never seen him try to take the lead or get angry when losing a game. And his faith in God was sincere.” Grand Duchess Olga used to say that the tsar’s subjects interpreted his composure and restraint as coldness and primness. People either did not understand or did not want to understand neither him nor his spouse.

The society attributed every misery to the emperor, whereas Nicholas II often covered up the faults of others with his mercy. The grand duchess related how the holy tsar secretly helped the victims of the Khodynka tragedy [a catastrophic crowd crush on Khodynka Field on the outskirts of Moscow occurred on May 18, 1896, during the festivities after the coronation of Nicholas II, as a result of which no fewer than 1,389 people were trampled to death and at least 1,301 injured.—Trans.] from his own funds. She referred to his difficult situation as a politician: “He constantly lacked experienced and disinterested ministers. As for intellectuals, they were speaking only about revolutions and attempted murders all the time, and they ultimately paid for this.” The tsar did not lose courage in that difficult environment, foreseeing the trials that awaited him: “He did not know fear. And, at the same time, it seemed that he was ready to die.” Olga Alexandrovna spoke about the motives behind the holy passion-bearer’s abdication, having first-hand knowledge of the situation with his circles: “Not only did he want to halt the wave of disturbances, he also simply had no alternative. He became convinced that all the army commanders had abandoned him—all with the exception of General Gurko supported the provisional government. Nicky [that is, Nicholas II] couldn’t even rely on the lower ranks of the army. He saw that he was ‘surrounded by treason, and cowardice, and deceit’.”

As is generally known, at the beginning the lot of Empress Consort Alexandra Feodorovna, the tsar’s spouse, turned dramatic as well. She was surrounded by gossip and rumors, her every action was misinterpreted, and even her shyness was mistaken for arrogance. Those tall tales turned into slander. Grand Duchess Olga used to say, “I can no longer read all these false accusations and abominable lies written about her.” Although everybody at the court was aloof from her, the relations between the young empress consort and the grand duchess were fine. Their simplicity of tastes, lack of love for high society and its mores, and compassion united them.

After 1904, Grand Duchess Olga became especially close to the imperial family: she visited them every day, and at the time of their withdrawal from the high society of St. Petersburg [then called Petrograd] she became their confidante. “It was such a joy for me to be among them. Their mutual love was my source of inspiration, and I loved my four nieces,” she used to say. Olga Alexandrovna took an active part in the royal children’s upbringing, she would often take them to St. Petersburg and arrange evenings with their peers there. She was particularly attached to her youngest niece, Princess Anastasia, perhaps recognizing some of her own traits in her—liveliness and a sense of humor.

The martyrdom of Nicholas II’s family was a painful subject for Olga Alexandrovna, and so she tried to avoid it. “Her reverence for the memory of her brother and his family was so strong that it couldn’t be expressed in words. The wound inflicted on her by the savage atrocity in Ekaterinburg never healed, nor did it turn into a scar,” her biographer Ian Vorres wrote. Sometimes this innermost secret of her soul was roughly and tactlessly infringed upon by the impostors who claimed to be the ‘surviving’ children of Nicholas II and who literally burst into her house. But even then Olga Alexandrovna showed boundless patience and love. She referred to one Frenchman who once appeared on her doorstep at night and posed as the “survived” Tsarevich Alexei this way: “We felt very sorry for him and agreed to read his manuscript.” Though we can imagine how much this reading hurt her.

Ian Vorres wrote: “One day I took the liberty of asking the grand duchess whether she prayed for him [that is, Nicholas II]. She was silent for a while and then replied: ‘I pray not for him but to him. He is a martyr’.”

Acts of mercy

Olga Alexandrovna was a true patriot. A sense of continuity of history was developed in the royal children from infancy: “Russian history was understood as an integral part of our lives – something close and intimate—and we were absorbed into it without the slightest effort.” Like her father, Olga adhered to conservative views concerning Russia’s special path, the monarchy and traditional values.

First of all, for Olga Alexandrovna, belonging to the House of Romanov meant serving her people and her fatherland: “There was a bond between the tsar and the people that was hardly understood in the West. And this bond had nothing to do with the enormous bureaucratic apparatus. The tsar and the people were bound together by means of the solemn oath that he swore during his coronation ceremony; the tsar pledged himself to rule, judge and serve his people. In a monarch the will of the people and the tsar’s office were joined together.” Once Germany declared war on Russia, the grand duchess together with her Okhtyrka Hussar Regiment (whose chief she was) went to the front and first stopped near the town of Proskurov (now the city of Khmelnytskyi in Ukraine).

The royal duchess became a simple army nurse: she dressed wounds, was present during operations, and was not squeamish about dirty labor. She helped the wounded even in the line of fire, for which she was awarded with the military Order of St. George, fourth class. “I have no time to go outside at all,” Olga wrote in one of her letters. “Yesterday I dressed wounds for eight hours, and three days ago we worked for ten hours without a break and hastily gulped down our food outside the regular hours. I like to have great amounts of work.” By that time she already had gained experience in work at a hospital—she had learned basic medical treatment at her Olgino Estate.

Doctors, medical nurses and the wounded at the Evgeninsky Hospital no. 1 of Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna.

Doctors, medical nurses and the wounded at the Evgeninsky Hospital no. 1 of Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. All shortfalls at the front concerned Olga very much, as she felt her personal responsibility for all that was going on. With her own funds the grand duchess equipped the principal hospital of Kiev, the director and patron of which she became. Olga Alexandrovna continued her work even when she was pregnant with her first son. Despite the horrors of war that she witnessed, Olga was not consumed with hard-heartedness at all: “I wept over each of them. It is terrible how it tears your heart. You get accustomed to the gravely sick and love them as if they were your own children; but suddenly they die.” Paying her last tribute to the hussars of her regiment, Olga would close their eyes and lay an Akhtyrka icon of the Mother of God medallion on their chests.

Grand Duchess Olga sponsored and was patroness of over 100 charitable institutions and organizations—orphanages, hospitals, almshouses, and women’s courses. People would often appeal to her with their personal requests, and the duchess did not turn anybody down, feeling it was her duty to support all who needed aid.

In emigration, Olga Alexandrovna’s house became a center for all those who shared her fate and drank the bitter cup of exile. The duchess did not stop her charitable activities abroad: pictures that she painted were exhibited in the capitals of several European countries, and income from the sale was used to support Russian emigrants in difficult financial situations.

During the Second World War, Olga Alexandrovna helped all her compatriots in the camps with food and clothing, putting herself at risk. It should be noted that she never supported the ideas of certain emigres who sided with the Hitlerites: She regarded backing of a country that had twice declared war on Russia as a tragic delusion. Nevertheless, after the end of the war the Soviet authorities addressed a note of protest to the Danish Government in connection with the activities of Olga Alexandrovna: She was accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”. Even the royal family was unable to help her in that situation, so together with her family she went to Canada as “agricultural migrant workers”, which meant compulsory work on a farm. Her family found itself in rather strained circumstances. Apart from seasonal farm labor, selling pictures was an additional source of income. Despite everything, Olga Alexandrovna even there tried to support the Russian diaspora as much as she could.

A special sphere of the grand duchess’ charitable activity was aid to the Church. She was well aware of the persecutions against the Orthodox faithful in the Soviet Union and aided them as much as she was able. Ian Vorres wrote: “Olga Alexandrovna maintained contacts with numerous Russian Orthodox communities, and, well-informed about their reduced circumstances, she was very moved by the lack of complaints and lamentation in their letters. From time to time she sent them small presents, finding money from her budget. Russian monks from Mt. Athos offered up daily prayers for her. When I was visiting their monastery and told them about my contact with Olga Alexandrovna, they began to cry and asked me to take an icon to Canada for her. The walls of her bedroom in her cottage were covered with icons that had been bequeathed to Olga Alexandrovna by many men and women who remained as faithful to her as at the beginning of the Revolution.”

Olga Alexandrovna reposed in the Lord in 1960 at the age of seventy-eight. Her funeral service was performed at an Orthodox church in Toronto. Officers of the Twelfth Okhtyrka Hussar Regiment of Her Majesty Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia (with whom she had been through the war and all of whom she remembered by name till very old age) stood guard.

Creative work

Olga Alexandrovna showed interest in painting from her childhood. Teachers would allow her to draw during lessons because it enabled her to master the content. Her father, Emperor Alexander III, who himself was a keen collector and connoisseur of art (his collection was the foundation of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg), encouraged his daughter’s passion. The princess was taught by the best teachers of painting: Kirill Lemokh, Vladimir Makovsky, Stanislav Zhukovsky and Sergei Vinogradov. In emigration, Olga Alexandrovna improved her skills by visiting art galleries. Her paintings were sold in London, Berlin, and Paris. Connoisseurs of art from European high society became possessors of her paintings.

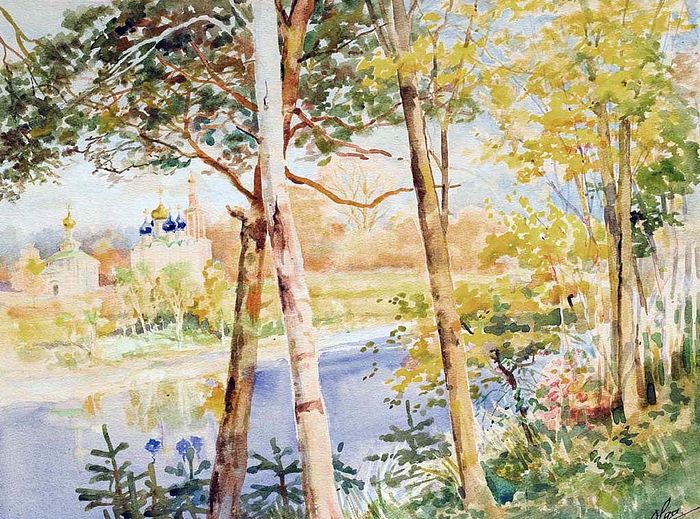

The most famous paintings by Olga Alexandrovna are landscapes and still lifes, though it should be mentioned that she also painted icons, with which she blessed her relatives, schools, almshouses, orphanages. The grand duchess had a subtle perception of her homeland’s nature, reflecting it in her delicate watercolors.

Her works are lyrical, and the apparent simplicity conceals a world view that was gained through much suffering. She found inspiration in the seemingly everyday things, such as flowers on a window-sill, a holiday pie or a jug on the table.

The simple joys of life in the era of world catastrophes and personal tragedies found their place on the canvases of “the last Grand Duchess of Russia”. No wonder that she continued to create peace-filled paintings on the frontline, witnessing all the horrors of the twentieth-century war: “A Hospital Nurse during a Stroll”, “Autumn in a Park”, “An Autumn Landscape”. Or in the Crimea, being practically under arrest, fearing for her family out of uncertainty: “Flowers in the Crimea”, “A Blossoming Tree and Cypresses”, “A Road in the Crimea”. Or, hiding in a Cossack village, where a simple peasant woman assisted her in childbirth and where the Red Army could encircle them at any moment: “Tikhon with a Nanny. The Novominskaya Stanitsa”, “Sleeping Gury”. Being almost between life and death, she painted joyous spring landscapes, blooming gardens with village girls talking by the fence. The duchess appears in her work ever resilient, able to see beauty in everyday things, thankful for every new day, simple, meek and inspiring.

The move to Canada opened a special page in her creative work. This northern country reminded Olga Alexandrovna of her “native expanses”, and the duchess returned to the Russian themes. A lonely church, a road that is lost to view amid snow-covered fields, a coach-and-three—her forsaken yet ever-beloved country comes back to life on her canvases. And an icon-lamp glimmering beside icons on one of her paintings reminds us of what gave this fragile yet courageous woman strength in all the trials: “The simple, childlike faith in the God of her forefathers and her people ran through like a thread of pure gold, illuminating the darkest pages of her life.”

O Holy Royal Martyrs, pray for us