OrthoChristian.com continues its endeavor to publish material on the theme of the 1917 revolution towards the end this centennial year. In this article, Vasiliy Shchipkov, who holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Moscow State Institute of International Relations, discusses the Christian approach to remembering the terrible time of Soviet repressions vs. a mentality of retribution.

Great Consecration of the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery. Photo: G.Balayants / Pravoslavie.ru

Great Consecration of the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery. Photo: G.Balayants / Pravoslavie.ru My family knows about repressions, about political and religious persecutions, not from reading modern history, but from its own life.

My great-grandmother Felicia Piotrovskaya was a prisoner of the Solovki Special Purpose Camp (known in Russia as “SLON”) located on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea in the 1930s. As a result of a false denunciation, one of my great-grandfathers, Vasily Polkovnikov, was imprisoned during these same years in the Altai, on the opposite edge of Russia. Later, in the early 1980s my grandmother, Tatiana Shchipkova1, a French and Latin teacher in Smolensk State Pedagogical Institute, was sentenced (at age 50) to three years in a Soviet labour camp for her Orthodox faith and for her refusal to educate students according to atheistic values. The camp was in the Russian Far East. Later she described this part of her life in a book titled Portrait of a Woman in the Prison Interior. It was a famous case, widely known among Soviet dissidents and leading Western media.

My parents, quite young at that time, were dismissed from the Institute “for their faith” (they were students at the same Institute where my grandmother taught) and had to live in excluded and marginalized conditions for many years. They brought up three, later four children with no chance of getting well-paid or intellectually-rewarding jobs, and were excluded from full membership in society. I belong to the first generation of our family untouched by repressions or persecutions.

It is because I have been brought up on this history, feeling myself an integral part of it, and because this is my family history, that I have a moral right to talk about repressions in a way that is more complex and multi-dimensional than is often expected by modern mass culture.

My family remembers. But the lesson of this memory of repressions and persecutions for us and for many Russians is not one of despair, hopelessness and the “feast of death”; it is, instead, the struggle of the human spirit and the moral victory over death. I am convinced that such an attitude toward the history of political and religious repressions can prevent a repetition of them in the future, and can build up Russian society rather than tear it down. Otherwise, we risk paving the way for forgetting the real sense and importance of the tragedies of the past. We risk those tragedies being used for political manipulation, and we risk allowing them to be used to justify an even greater evil today, and in the future.

“How is such a thing possible?” you might ask.

***

Just a few years ago the discussions in Russia on the theme of Soviet repressions were still polarized around the issue of their scope and the role they played in the life of society. “Are you ready to recognize the repressions as the determining fact of Soviet history or not?”—such was the alternative suggested in most of the discussions, from academic conferences to TV talk-shows. Now the picture is very different. Almost no one questions the fact of repressions. “There is no justification for these crimes,” stated Vladimir Putin at the commemorative ceremony at the Katyn Memorial near Smolensk: “In our country, we have passed a clear political, legal and moral verdict on the atrocities of that totalitarian regime. And this verdict cannot be revised2.”

The discussion has now shifted to determining who has the moral right to explain and interpret these historical facts.

One can identify two opposing visions of repressions in modern Russia.

The Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery

The Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery The first one is based on forgiveness and can thus be called the Christian one. The second one is based on revenge and retribution and can be called “secular.” The term “secular” needs to be in quotes because the secular consciousness substantially reflects some implicit religious grounds. I. Baily has called this phenomenon a “secular faith”. Moreover, this vision is usually, though not always, associated in Russia with the so-called “protesting” and “liberal” part of society. However the contrast is not explained purely by political differences. Rather it lies in the sphere of philosophical perceptions and ethics.

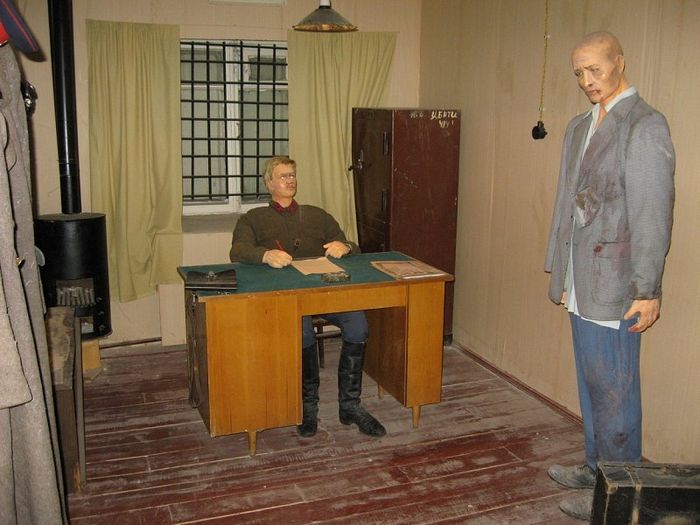

The Christian response to the memory of the Soviet repressions requires forgiveness – the appropriate tribute is to build a church to commemorate the memory of victims3. The “secular” group offers its own tribute by physically reconstructing the Gulag, often in the form of historical museums or landmarks. Let’s then figuratively call these sides the “Church” and the “Gulag-museum”.

The group advocating Gulag museums cultivates hatred against “Stalin’s butchers” and their successors. The “butchers” are presented not as historical characters, but rather as embodiments of absolute evil, as a kind of 20th century Behemoth, destroying people without any reason or purpose.

When one enters the secular Gulag museums, one gets the feeling of a certain emptiness, the victims presented as wholly unfortunate people who left this world without any sense or message left to posterity except the one of revenge and bitterness. They are neither saints nor martyrs. They are just victims, who continue suffering even after their death, intended to be perceived by visitors as depersonalized symbols of pain.

As in the images in the famous sculptural series “The Masks of Sorrow” by the well-known nonconformist4 artist Ernst Neizvestny, the victims in these sculptural compositions look at us with a kind of condemnation and emptiness inscribed in their faces, as if imploring us to reciprocate the evil that had been done to them. Their voices are not heard. We only see that their dreams were not fulfilled, are not fulfilled and never will be, due to the mere fact of their death, which in a non-Christian view is the end of everything. Any personal contact with them is impossible—not on the physical, and even less so on the spiritual level.

Visitors feel their own guilt before the victims; they experience hopelessness, severe depression and anger. The “secular”, non-Christian view is centered on our earthly world. This view is not metaphysical. It is easy to direct this anger against the successors to the USSR—the modern Russian state, “Putin’s regime”, anyone the “Gulag museum” doesn’t like.

Aesthetically, the average “Gulag museum” has almost become an epitome of the dehumanization of modern art. It is ostentatiously anti-aesthetic and provocative. As an element of modern counter-culture it calls for revenge not only on the executioners but also on the whole epoch in which such injustice became possible. This generally negative attitude spreads itself to non-state actors—Soviet writers, Orthodox Christianity, classical Russian education, everything that reminds the “Gulag museum group” of a Russian national tradition. Even by its visual impact such museums reflect the atheistic rebellion of Ivan Karamazov and Nikolai Stavrogin from Dostoyevsky’s novels: “Where was your God, who admitted such suffering and pain?” But, unlike Dostoyevsky, they give no answer.

This sort of attitude to the Gulag is perhaps best summed up by the slogan of anti-Putin protesters in 2011: “We won’t forget, we won’t forgive”. Guided by the logic of revenge, the “Gulag museum group” sees in the plight of the Gulag’s victims a sort of legitimization for a massive and even cruel retribution. Since the perpetrators of those crimes are now dead or extremely old, the revenge advocated by the “Gulag museum group” is redirected from individuals to the Russian Orthodox tradition, and even to any elements of the Russian national tradition at all.

Since this cultivated vengeance is huge, it needs sublimation against something similarly huge, but of the opposite spirit. The foundation of the Russian cultural tradition, Christianity, is exactly that kind of thing.

In short, the aesthetic of the Gulag museum reflects anger and helplessness before such a terrible fate. This anger evokes the sense of an insurgent’s freedom. This aesthetic allows those drawn to it the thrilling sensation of being akin to the “masters of modern Russia:” the delights of being in the right, in rebellion, and in control, all at once.

This is the logic they follow: if the evil perpetrated against them (or, rather, their ideological predecessors) is so huge and unforgivable, then, as Ivan Karamazov says, “Everything is permitted” to the Gulag museum group: the unbinding of the most terrible human emotions in a world without God. If life has no continuation after death, then a non-believer has the full right to take his or her revenge on life itself for his or her imminent death.

This non-Christian perception of the repressions becomes a protest-oriented political technology.

Thus, in contemporary Russian speech, words and phrases like “political repressions”, “Gulag”, “Stalin’s victims”, “Chekists”, “reports on persons’ political convictions” have been given a private and partisan meaning, appropriated on behalf of liberal and protesting discourse. This lexicon serves as a historical backup for a modern day protest, becoming a powerful tool in the hands of anti-state activists and opinion leaders.

Such a tool is used not just against the past, but also against the present-day state. The key aims of this discourse are well known and have not changed for decades: a tribunal for the Soviet regime resulting in the “de-Sovietization” of Russia on the model of the modern Baltic states and post-Maidan Ukraine.

These measures are supposed to lead to a kind of repentance of the Russian people for the Soviet period of history—before the so-called “international community” in its present Westernized variation. As its final stage, this scenario presupposes a thoroughgoing revamping of the cultural identity and of the historical values of the Russian people. Such a technology helps to yield easy and short-term political dividends by converting the “fission” of tradition and of historical memory into a socially destructive energy. The nature of this protesting technology has nothing to do with the promoting of real national health and justice. Inspired by non-forgiveness and revenge, it remains indifferent to any actual reforms that might be needed in the present state. It seeks only to implicitly divide society into “the victims” and “the executioners”, people on the “good” and “wrong” side of history, “the judges” and “the accused”, “the enlightened” and “the rabble”.

Great Consecration of the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery. Photo: G.Balayants / Pravoslavie.ru

Great Consecration of the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery. Photo: G.Balayants / Pravoslavie.ru

The Christian group and its vision of the phenomenon of repressions suggest a completely different attitude. It does not curse the locations and memorable events connected to the death of the innocent. The Christian attitude sanctifies these sites and events. This attitude follows the aesthetic and the theology of an Orthodox church service, where the story of the persecuted (or as we might say today, “those subjected to political repressions”) God is retold and remembered every day.

Prayers at the site of repressions curse no one. The object is rather to establish a personal connection between the praying person to God and the slain innocents. Victims are no longer the irrevocably lost entities crying for revenge, as they are in the discourse of the Gulag museum group. On the contrary, in the Christian context, victims of repressions are seen as immortal souls, imploring your prayers, not your revenge. Many Christian martyrs can be found among them, some of whom have been sainted officially. But there are also many unknown saints.

These saints died not with a curse on their lips, but with a prayer for Russia. In the same way, those belonging to the Christian group visit these Christian temples devoted to the Gulag’s victims with a prayer, not with fury, in their hearts. They want to offer to the slain ones their own “bloodless sacrifice”. As it is written in the Psalms, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise”.

The spirit of the Gulag museum groups is quite different: They come to get an adrenalin injection from a history-based horror show. Such adrenalin doesn’t heal the pains of history, or the suffering of society. It simply acts as short-term anesthesia.

According to the Christian worldview, the evil leading to suffering and death is something inside humans, and it needs to be eradicated by love and prayer, not by revenge and despair.

Even Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who never concealed his hatred of the Soviet justice system, and whose Gulag Archipelago became one of the most famous accusations against the Soviet repressions, warned “the reader who expects this book to be a political exposé” to “slam its covers shut right now.”

“If only it were all so simple!” he observed: “If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

A Gulag museum without Christian forgiveness little by little acquires the feel of a ride in a horror theme park. Such a museum won’t assuage the nation’s wounds. If we want the memory of this tragedy to strengthen the moral force of society, the monopoly on this memory needs to be wrested away from the so-called political technologists and managers. The memory of repressions in Russia needs to be returned to its people and filled with a Christian, pious spirit.

The Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery. Photo: V.Khodakov / Pravoslavie.ru

The Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church in Sretensky Monastery. Photo: V.Khodakov / Pravoslavie.ru The Christian faith does not seek the death of its enemies, but rather a spiritual healing of the people, with the healed ones including not just the saints, but also the worst criminals. As I live, said the Lord God, I do not desire the death of the wicked but that the wicked turn from his way and that he live (Ezekiel 33.11). We can hardly heal “the wicked” ones of the past, but we must think of preventing our contemporaries and coming generations from becoming hardened and embittered.

Just as the cross, once an instrument of torture, became a symbol of eternal life and God’s love for humans, in the same way the memory of the repressions needs to become not a school of hatred, but a school of love.