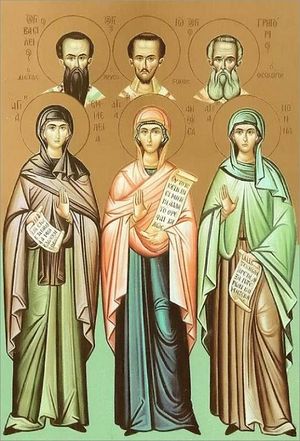

The Holy Hierarchs Basil the Great, John Chrysostom and Gregory the Theologian (from left to right) with their righteous mothers, Sts. Emmelia, Anthousa, and Nonna.

The Holy Hierarchs Basil the Great, John Chrysostom and Gregory the Theologian (from left to right) with their righteous mothers, Sts. Emmelia, Anthousa, and Nonna. What am I driving at? There is no shortage of righteous people in heaven, but there is lack of our hagiographic literature. And whenever the mother of a large family or a simple worker asks me how they should live their lives according to the commandments, I cannot give them an adequate example (the examples of St. Anthony the Great or St. Seraphim of Sarov don’t work, at least because their ways of life were completely different). I cannot cite the Lives of the Holy New Martyrs Tsarina Alexandra or Grand Duchess Elizabeth (who are deeply venerated by all) as examples either. Only a handful of episodes and details from their Lives will serve as models for a modern housewife. The problem is that neither of these two saints had the everyday chores of an ordinary housewife: cooking, laundry, cleaning, kids, work… Then how to combine these endless cares and daily routine (something that many women are fed up with doing) with spiritual life, with Christ and fulfilment of the commandments of God today? This is a difficult problem (that appeals to both clergy and laity) to solve.

And here we will need to imitate St. Anthony the Great in gaining experience gradually from different sources. At the very beginning the Venerable Anthony did not have a fixed rule of ascetic life in the desert, so he referred to experienced ascetics for advice. He visited various famous monks seeking the much-desired experience. Thus he observed the diet of one, the prayer rule of another, adopted the customs of vigil and sleep hours from another, and so forth. For want of other possibilities we have to accumulate the experience of saints from books, but only those saints whose lifestyles were (to varying degrees) similar to ours, and take only the episodes from their Lives that are close to our circumstances.

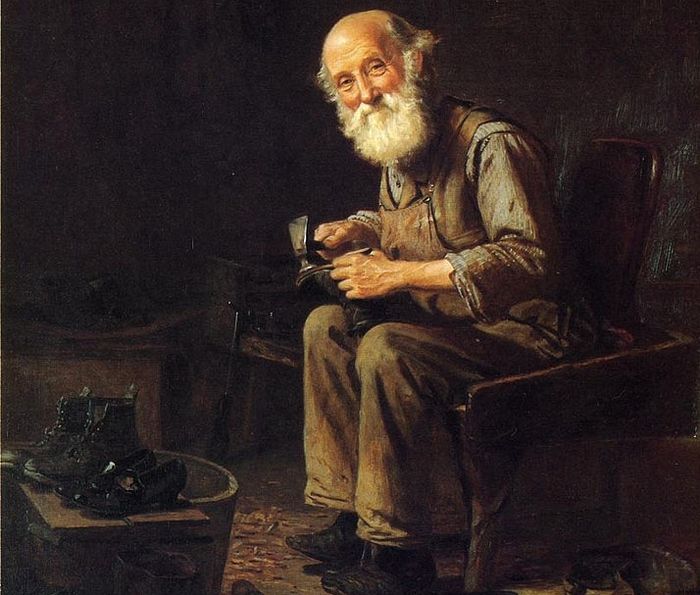

And Abba Anthony the Great is the first to teach us. One day when St. Anthony was praying in his cell he heard a voice, saying, “Anthony, you have not yet become as perfect as one poor cobbler living in Alexandria!” The holy man immediately made for Alexandria, found that cobbler and persuaded him to reveal the secrets of his spiritual life to him. “I have never done anything good. So when I rise in the morning I always say to myself before setting to work: ‘All in this city, young and old, will be saved and enter Paradise for their good works. And only you will be damned and suffer everlasting torment for your sins!’ Every evening before going to bed I repeat the same words to myself from the bottom of my heart,” the cobbler said. This is a lesson of humility and meekness.

The second example, this time from the Life of St. Macarius the Great, is widely known as well. Once while the saint was praying he heard a voice telling him that he had not attained such level of perfection as had two women who lived in the city. The lowly hermit obeyed and went to the city. He eventually arrived there, found the house of the women in question and asked them to tell him about their good deeds. And this is what they answered him: “We married two brothers. And over many years we have never uttered any malicious or shameful words and have never quarreled among ourselves. We asked our husbands to allow us enter a convent, but they would not permit us. Besides, we vowed not to utter any worldly words till the end of our lives.”

This example is close to us in terms of circumstances, yet we are as far from these women as it is far from the earth to the sky, as it were. They are not ranked among the saints, yet you can feel the breath of holiness in these several lines. Imagine two housewives in the same kitchen who have never quarreled or insulted each other, or two women in the same house who never twaddle! It is a podvig [a Russian word meaning a spiritual labor, exploit, feat that requires great effort] and a result of podvig. In order to have such power and control over the tongue one needs to fast and pray unceasingly. Outwardly it is secular life, and in essence it is monastic life. According to St. Ephraim the Syrian, “It is not tonsure and garb that makes the monk, but a heavenly desire and Divine living, because in this lies perfection in life.”1

The next saint that we will take as a model lived in Russia. The Righteous Juliana of Lazarevo (also known as Juliana of Murom) was born in about 1530 and reposed about 1604, her feast-day is January 2/15. The future saint was born to a noble family and her parents were well-off. If she had not become an orphan in her childhood, she would surely have lived in a happy family. Her grandmother took care of little Juliana and after the former’s death her aunt took the twelve-year-old girl into foster care. The saint never enjoyed children’s games and fun, instead devoting most of her time to fasting and prayer. She did diligently any job she was charged with. The girl liked needlework, especially sewing and spinning. Young Juliana would stay up working throughout the night, yet she sewed clothing not for herself but for the poor.

At the age of sixteen Juliana was married off. Her husband was often called up for the royal military service, so Juliana would stay alone running the household. As before, Juliana sewed clothes for the needy, cared for widows and the orphaned, doing it without her parents-in-law’s knowledge. During a famine she would give away all her food to the hungry, herself not having enough to eat. When the famine was followed by an epidemic, the saint would secretly wash the sick in bathhouses (while many were afraid even to touch clothes of infected people), treat them, wash and bury the orphans and paupers who had become the epidemic’s victims.

St. Juliana became a mother of thirteen children of whom six died in their infancy. As soon as her children grew up, the holy woman intended to enter a convent, but her husband persuaded her to remain in the family. Thenceforth they abstained from marital relations until her husband’s death. While her husband continued to sleep on their original bed, Juliana would sleep on the stove2, standing logs end up for a bed and putting iron keys under her side. Thus she would fall into a deep sleep for an hour or two. As soon as everything became quiet, the righteous woman would get up and spend the whole night in prayer. In the morning she would go to church for the Matins and the Liturgy. After services she would return home and do housework. On Mondays and Wednesdays the saint ate only once a day, while on Fridays she would abstain from food, retreating into a separate room within the house that she used especially for prayer in solitude. She could drink a glass of wine only on Saturdays when she received and fed priests, widows, orphans, and the needy.

Acts of charity were most important to St. Juliana. Though she often remained penniless, she would borrow money and immediately give it out to beggars. She would donate the money intended for purchasing her winter clothes to the poor, spending the winter without warm clothes and wearing shoes on her bare feet. For mortification of the flesh the woman ascetic would put pieces of broken crockery under her bare feet into her shoes and wear them thus.

There was a harsh famine during the reign of Boris Godunov (1598-1605). St. Juliana sold virtually all the things she had possessed, gave freedom to her kholops [feudally dependent people in Russia until the early eighteenth century whose legal status was close to a serf. –Trans.], though some of them preferred to stay with their saintly mistress whom they loved dearly. In those years Juliana would bake bread with a mixture of orach (saltbush, mountain spinach) and bark and distributed it among children, servants and beggars. And that bread seemed tastier than wheat bread…

Living in want for two years, St. Juliana never complained, grumbled or lost heart, instead remaining vivacious and happy as ever. The holy woman was always amiable, open, affectionate and kind to everybody. She comforted others with wise words, though she was illiterate and her sole “teachers” were church services and prayer. Before her death St. Juliana became sick: she would lie in bed during the day, but at night she would get up to pray. “I have always longed for monastic life since my youth, but have not become worthy of it for my sins… But glory to the righteous judgment of God!” she said to her nearest and dearest gathered around her deathbed.

Thus she passed away in 1604—an earthly angel and a heavenly woman. Ten years later her incorrupt relics were uncovered and numerous miracles occurred.

Now we see the image of a holy woman who lived a godly life and was righteous in all her ways. Her Life is not even a lesson for us to learn. If anything, it is a judgment. How can we justify ourselves now, in our own eyes? What excuses will we make to the Righteous Judge in eternity? We are lazy, idle, inattentive, irritable, pleasure-loving and selfish.

We tend to deceive ourselves claiming that we are always very busy. We can even find the following excuse: unlike us, St. Juliana was a wealthy lady of the manor and had servants. True, she did have servants and was a noblewoman not a peasant woman. But if we compare her life with that of princesses and tsarinas, we will find that her way of life was much closer to us ordinary lay-people. Despite her noble blood St. Juliana was illiterate, and despite her wealth she lived from hand to mouth. We see from her Life that though she had servants, she preferred to toil herself from morning till night. The saint did not allow her maidservants to dress, or undress, or attend upon her, as was the case with noble ladies of that time. Over her lifetime Juliana experienced joy and suffering, married life and widowhood, prosperity and hunger. Yet she was never bent under the weight of the heavy cross she had to wear, even when her children died or when she ate bread made of grass.

What is the main difference between us and her? When it comes to moral and spiritual life, the huge chasm of 400 years between us vanishes. Spiritual laws are always the same. What do we do in our days? We spend hours surfing the net, watching TV shows and talking over the telephone. In old days people held receptions and sumptuous banquets or went to fairs for this purpose. Modern technologies are not necessary for idle talk—only one female neighbor will suffice. And for wandering of mind we need absolutely nothing! But in order to overcome these temptations we need courage and resolution, prayer and ardent effort. We don’t have any of this, neither did most of people in the sixteenth century. But St. Juliana acquired these virtues.

Windbags argue that spiritual labor and prayer are not really necessary for salvation in married life in the world and that there is not even room for them in family. “Just try to keep the commandments, that is enough,” they say. But the problem is that there is no salvation without spiritual labor and prayer. And there is space for them in any situation. You are tired after a working day, have no strength, but you have to read your evening prayers. And it is here that your spiritual struggle begins. Your head is humming, feet are aching and you feel that you will die on the spot unless you sit down or lie immediately. And there is a saying: “Better pray while sitting than think of your sore feet while standing”. But, believe me, if you give up today, you will surrender tomorrow as well. For if you yield to demons now, tomorrow they will carry you where you don’t want to go. Praying in this state means shedding your blood for Christ. Spiritual struggle is Christianity in action. The spiritual labor is performed inwardly, it is when you are fully determined to renounce all for Christ’s sake and observe His commandments.

Outwardly, the spiritual labors of laypeople are different from those of monks. We cannot retire to seclusion as hermits do, but we can find a place to stay alone during the day. We cannot take a vow of silence, but we can be silent for a while. We cannot become stylites or wanderers for Christ or live in total obedience; nor can we cease to bathe or bother about this-worldly things. But, unlike ascetics, what we really can do is doing acts of charity, taking care of our families and giving love to our children. And, of course, nothing prevents us from fasting and praying.

All of us, both laypeople and monks, have a common goal—to overcome our sins and passions, to cleanse our souls and acquire the grace of the Holy Spirit. And we may need many instruments, including chains and fetters, to succeed in this. The Holy Grand Duchess Eudoxia of Moscow (monastic name: Euphrosyne; 1353-1407), wife of the Right-Believing Prince Dmitry Donskoy, helped her son Vasily I rule over his principality after her husband’s death. These duties entailed a lot of bustle and required vigilance. So the holy duchess, emaciated with fasting, used to bear chains underneath her rich garments. She was canonized as “the Venerable Euphrosyne”, though she lived only two months after receiving the tonsure. Indeed her entire life, filled with fasting, prayers and vigils, was monastic.

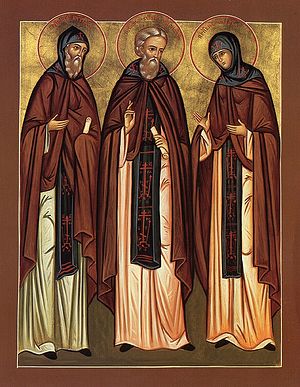

The family of St. Basil the Great. From left to right: St. Gregory Nazianzen (brother), St. Macrina (grandmother), St. Emelia (mother), St. Peter of Sebaste (brother), and St. Basil the Great.

The family of St. Basil the Great. From left to right: St. Gregory Nazianzen (brother), St. Macrina (grandmother), St. Emelia (mother), St. Peter of Sebaste (brother), and St. Basil the Great. What will we reproach them with? If some of them had servants, now we have washing machines, central heating and running water. While some of them had riches, they gave all that they possessed to the needy. If we argue that that time was different from ours, we will be wrong, because our aim is the same at any time: to labor for our salvation and please Christ. And we never have much time, as life is so short.

Please be considerate and careful. We will all be judged at the end and who are we to judge God’s holy and honored saints and how they chose to live while seeking to please God? May we silently sit at their feet and learn from them. God will judge both is and them, may we strive to be holy and may we seek his mercy continually.