Our first meeting with Nun Silouana was connected with Jerusalem. Though we did meet and communicate with her at the Orthodox Convent of the Protection of the Mother of God in Bussy-en-Othe (the Yonne department of France) where she lived for about twenty-five years, at the St. Alexander Nevsky’s Cathedral in Rue Daru (Paris), and in Moscow, our plan for a joint trip to the Monastery of St. John the Baptist in Tolleshunt Knights (Essex, the UK), founded by Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov; Mother Silouana’s spiritual father), remained unrealized.

Mother Silouana (secular name, Tatiana) was born in Moscow (the native city of her Russian mother) in 1953. Her father, Leo Ovsishcher (1912-2007), who was a military man, war veteran, scientist, “refusenik” [a Jew in the former Soviet Union who was refused permission to emigrate to Israel.—Trans.] for sixteen years, hailed from Belarus. So it was in Minsk that the future nun spent the first twenty-five years of her life prior to her emigration to Israel in 1979.

In the 1970s, the Soviet authorities sometimes allowed this emigration of Jews by calling it “family reunification”, but if you were denied permission to leave the country it meant the loss of your job and the end of your career in the Soviet society. Tatiana’s mother passed away in Minsk in 1980, while her father wasn’t able to move to Israel until 1987, when he finally emigrated and resided in Jerusalem till his death in 2007. He is buried at the most ancient Jewish cemetery in Jerusalem, situated on the Mount of Olives.

Before her emigration from the Soviet Union Tatiana married and took her husband’s last name. Later they moved to Israel together, yet their marriage did not last long. The family breakdown was probably her main reason behind moving from Israel. Though Mother Silouana once said: “Today Israel is interesting. You cannot imagine what life in the late seventies’ Israel was like.”

Tatiana had been baptized in the Soviet Union, so she emigrated to Israel as an Orthodox Christian. This is precisely what brought us together during our first meeting at Bussy-en-Othe Convent: I was told that there was a nun from Jerusalem there, and she was told that a deacon had come from Jerusalem. In France Mother Silouana lived with her Israeli passport because she did not have any other passport. There is no information about Mother Silouana’s spiritual life in Israel—the church she attended or the contacts she maintained there. At least she never recalled any facts even during her subsequent visits to Jerusalem. However, in Europe she ended up at a convent.

Perhaps Tatiana intentionally came to the nunnery. On September 1, 1982, the future nun arrived at the Holy Protection’s Convent at Bussy-en-Othe in France and remained there forever. But it was not until eight years later (namely August 24, 1990) that Tatiana was tonsured a nun.

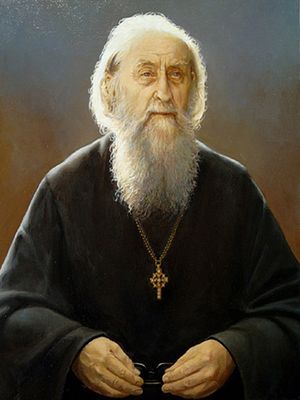

We don’t know when and why Mother Silouana took an interest in monastic life. One could suggest that all began with her failed marriage; however, failed marriages rarely lead to monastic life. One igumen told me that every monk or nun strives to imitate the spiritual mentor who inspired them to follow a monastic path. As for Mother Silouana, Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov; 1896-July 11, 1993), an Athonite monk, disciple of St. Silouan of Mt. Athos (hence the monastic name that she chose), and the founder of the monastery at Tolleshunt Knights in England, became her spiritual father and an example she could follow. She met Fr. Sophrony in 1988 during her first trip to Essex, several years after joining the Holy Protection Convent in Bussy-en-Othe as a novice. “Within the first few minutes of our first conversation Fr. Sophrony became the most important person in my life,” Mother Silouana wrote in her short article dedicated to the elder[1]. It was at Tolleshunt Knights that Mother Silouana became a nun. Fr. Sophrony was her sponsor during tonsure. When asked why she decided not to remain at Elder Sophrony’s double monastery (which has two communities: one for monks and one for nuns), she answered: “Isn’t it faithfulness to spiritual virtues?”

Mother Silouana was in contact with Elder Sophrony, her spiritual father, right until his repose in 1993. She would visit him in England and they would exchange letters for years. “Fr. Sophrony was a great man,” Mother Silouana wrote. “The reflection of his personality spread to everyone around him. Every time I visited Fr. Sophrony’s monastery it seemed that the whole community consisted of ‘spiritual giants’, that all the people who were close to the elder were on the same spiritual level as he… The elder saw Christ in every human being and had a great respect for everybody. He raised people who communicated with him to his own level; all became ‘great’, and any unimportance vanished. Truly he saw Christ in every person.”[2]

According to Mother Silouana, “There was one important theological statement of Elder Sophrony that had practical application: ‘Even if you are beset with passions, take it as part of the universal suffering of mankind. Don’t worry much about this passion. Just repeat: Lord, Thou seest the inner state of all of us (not mine, but all of us)! Please help!’”[3]

We tend to see the traits that we possess or that are developing inside us in other people. The way Mother Silouana described Fr. Sophrony in some sense enables us to see her own spiritual portrait. “In my life I have seen many monks who were reticent to speak about their spiritual paths. Fr. Sophrony was very different. It doesn’t mean that he opened up to others completely. He warned that we are reserved because we fear being wrong, thus rejecting the Holy Spirit (‘What if I err?’). Therefore, it is better to make a mistake than to reject the Holy Spirit.” Indeed Mother Silouana herself was an amazingly open-hearted, sincere and loving person. She was not afraid to speak about herself; in return, people were not afraid to open their hearts to her without hiding their problems and weaknesses.

And this is what she wrote about the elder: “Fr. Sophrony was an amazingly loving person. I knew that this person would love me regardless of my actions and my behavior; it was something that couldn’t be changed. He couldn’t be ‘today enchanted, tomorrow disenchanted; today in the right mood, tomorrow in a bad mood.’ His love did not cease! I think that every single person who knew Archimandrite Sophrony believed that the elder loved him more than other people. Such was the full extent of his love. I am made all things to all men (1 Cor. 9:22).[4]”

In addition to the spiritual component, human mutual understanding and human unity are essential for communication as well. Thus, the following moment was important to Mother Silouana: “Not only was Fr. Sophrony a monk and an elder, he was also a representative of the Russian intelligentsia of the early twentieth century. Even his gestures mattered: the way he walked, bowed his head, his intonations and turns of phrase…[5]” Perhaps the more you have in common as a human being the easier it is to establish and maintain contact with others.

But of course, not only human and cultural closeness matter. As Mother Silouana wrote: “The elder’s attitude towards the Liturgy was the most important thing. For the elder the Liturgy was the center of the universe. I have never experienced the Liturgy as I experienced it at his monastery anywhere else. I felt as if I were standing in heaven, the people around me were participating in the Liturgy, and the worshippers’ silence was saturated with the silence of the universe. It was only there that I ever had this feeling, this experience.[6]”

Mother Silouana’s favorite biography of the elder was the book by Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) of Nafpaktos, I Know a Man in Christ. The Life and Ministry of Elder Sophrony the Hesychast and Theologian.

***

Over the thirty-five years of her monastic life, Mother Silouana performed various obediences. One of them was cooking—and she was a brilliant cook. I more than once sat down at her table in Jerusalem when she was visiting her stepmother there, and I enjoyed her borscht at Rue Daru when the Russian cathedral there organized the days devoted to the Holy Protection Convent.

Mother Silouana ,who had an excellent voice and good ear for music, was a church choir director for many years (she also noted down the hynmographical tradition on the Russian Convent on the Mount of Olives). In the final years of her life, Nun Silouana was in charge of the convent’s archives. This work resulted in the publication of a number of books dedicated to nuns and abbesses of Bussy-en-Othe Convent. The history of female monasticism in the twentieth century Russia was among the main areas of her intellectual interests and study.

Mother Silouana’s books on female monasticism are very interesting. First and foremost, these are the books on Nun Taisia (Kartseva; 1896-1995) from the Holy Protection’s Convent who was a hagiologist; and on Abbess Eudoxie (1895-1977), the first mother-superior of Bussy-en-Othe. Not long before Mother Silouana’s repose, the French edition of her book on Abbess Eudoxie appeared. While Mother Silouana personally knew Nun Taisia and communicated frequently with her, she “knew” Abbess Eudoxie only through other sisters’ memories and through the convent’s archives.

Initially Mother Eudoxie wanted to found a monastic community together with St. Maria (Skobtsova; 1891-1945), but it turned out that they had two different approaches to monastic life. This proximity to Mother Maria (who was canonized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2004), coupled with a slightly different experience as compared with her active ministry in the world, became essential factors in the formation of a more “traditional” monastic community, founded by Mother Eudoxie at Moisenay near Paris, which moved to Bussy-en-Othe in 1946. This is what Abbess Olga (Slezkina; 1915-2013), mother-superior of the Holy Protection Convent between 1992 and 2013, wrote on the Martyr Nun Maria (Skobtsova): “Every single person has his own path. Mother Maria was a holy woman who laid down her life for others. She is a true martyr. She is simply not my type of a person and I don’t think she was a nun in the usual sense of the word. She used to say, ‘They make prostrations, but who needs them? Do you really think the Lord needs these prostrations? They make no sense at all!’ And so forth. You see, visions of monastic life may vary… Mother Maria accepted this type of monasticism and considered it the only possible way of living a monastic life. But everyone has his own path. She had this path, but others have theirs.[7]”

If the Church had reinstated the institution of deaconesses, Mother Maria would surely have become a deaconess rather than a nun.

It was not without reason that in the early twentieth century, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna petitioned the Holy Synod to reinstate the order of deaconesses. Since there are no deaconesses in the Church now, any ministry of this kind is called “monasticism”. Despite Mother Silouana’s sociable nature her monasticism was not oriented towards “social ministry”. After becoming a nun she spent the rest of her life at the convent and always wore her monastic habit, even in the metro of Paris and the airport of Tel Aviv. For Mother Silouana the core of monasticism was “the soul and God” rather than communal monastic living.

For the final five years of her life, Mother Silouana struggled with cancer; her condition was called spinal myeloma disease. It was the third cancer in her life, the previous two had been cured. During the first stage of her last illness she still did manage to travel to Jerusalem, visit her stepmother and stay at the Mount of Olives Convent. After that she had courses of chemotherapy, with frequent hospital stays and epiphenomena of the disease. Nevertheless, she was taken to church on Sundays and major feast days right until the end of her life. I last saw her roughly a year before she died: As usual, she was going to chemotherapy in hospital. And even then she was smiling. As the convent’s sisters told me later: “Mother Silouana never complained.”

Mother Silouana reposed in the Lord on June 29, 2017, at her convent.