With Sister Nectaria in front of the huge and splendid cathedral mentioned by the Venerable Porphyrios the Kapsokalyvite

With Sister Nectaria in front of the huge and splendid cathedral mentioned by the Venerable Porphyrios the Kapsokalyvite The dangers in Africa

Africa is a huge, marvelous and very dangerous continent. In Africa visitors are at risk of contracting many long forgotten or unfamiliar infectious diseases such as cholera, plague, malaria, yellow fever, Lassa fever, the terrible Ebola fever (the “African plague”), not to mention the extreme heat which is unbearable for Europeans. Although you won’t meet dangerous sharks or crocodiles in big cities, bites from malaria mosquitoes and other poisonous insects pose a deadly threat. Every year, malaria kills up to one million people in central and southern Africa.

In addition to infections, there are numerous other serious risks in Africa: many of its countries are in a deep political chaos, and for occasional European tourists traveling in Libya, Somalia, Congo, the Sudan, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Kenya, Angola, and Mauritania there is a very high risk of an armed assault, a terrorist act, kidnapping, hitting a mine, seizure by pirates, and rape.

Olga has died, now I am Nectaria

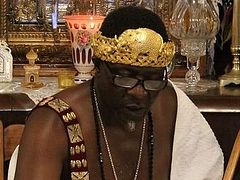

I could never imagine that a European resident (let alone a woman) would ever agree to live in one of these countries of his or her own free will where he or she would be continually exposed to various hazards. And just such woman is now standing in front of me: Mother Nectaria is a shortish elderly nun from the Convent of St. Nectarios from Aegina Island. Sister Theophila, a Russian nun of this convent, introduced me to Nun Nectaria, and Abbess Theodosia, the mother-superior, blessed Nun Nectaria to tell me about her missionary work in Africa.

Sister Theophila introduced us to each other with a smile:

“Do you know that all three of us are Olgas? Mother Nectaria and I bore this name before taking the veil, too.”

Sister Nectaria smiled as well:

“Yes, I was Olga many years ago. But Olga has ‘died’, and now I am Mother Nectaria.”

A pause that would befit Shakespeare

—Sister Nectaria, I hope you labored in the mission in one of the safest African countries, right?

—In Congo, formerly named Zaire. Since 1997, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

—Are you joking? In Congo?!

—Have you also been there?

—No, I haven’t. Frankly, I am not brave enough and I am afraid to think about such travels. I have read somewhere that Congo is the third most dangerous country of that continent. It has experienced continuous tribal warfare (in fact a simmering civil war) for many centuries. Cannibalism is still much alive there. There are also plague, malaria mosquitoes, and tsetse flies that spread sleeping sickness into the bargain.

The nun smiled and nodded in response:

—Yes, it is not a safe place to live in.”

—Sister Nectaria, can you tell me how many months you spent in Congo?

—Why months? I lived there for eight years.

There was a pause worthy of Shakespeare.

I dreamed of working in Africa long ago

—I dreamed of working in a mission in Africa long ago. With the blessing of my spiritual father I went to the Democratic Republic of Congo, to the town of Kolwezi that sits in the south of the country amid mountains.

—So am I right that it was your own idea to go there?

—Absolutely! I have always had a lot of sympathy for many Africans because of their unhappy lot.

We had to break off our conversation as the sisters were to leave and perform their obediences. They brought me some fruit, coffee, cold water, and Turkish delight, and left me alone at a terrace under a mountain pine tree by which the Holy Hierarch Nectarios of Aegina would converse with his spiritual children. The saint taught his disciples self-denial and monastic podvig [spiritual labor, exploit in Russian], revealing to them the transformed world where everything that had breath praised the Lord (cf. Ps. 150:6). While waiting for the sisters I connected to the internet to read about the Democratic Republic of Congo.

With Nun Nectaria under the very mountain pine by which St. Nectarios would talk with the convent sisters

With Nun Nectaria under the very mountain pine by which St. Nectarios would talk with the convent sisters One of the poorest countries in the world

Economically Congo is one of the poorest countries in the world, yet it is one of the richest countries in terms of natural resources. Therefore, it has been exploited by various criminal groups and corporations from all over the world. These corporations illegally build mines and pits, drive residents of neighboring villages into them, rape their women, and force men to labor until they die of emaciation.

Congo has the highest rates of rape and sexual slavery in the world, and the situation is aggravated by the fact that sexual violence directed at women is considered normal by the majority of the country’s residents.

When tourists are walking around Congolese cities, they lose their valuables and documents – they are snatched by criminals, ordinary residents, and youth street gangs. And it is useless to seek help from police because of high levels of police corruption in the country. So if you are stopped by a policeman in the street, you’ve got trouble.

It is also noteworthy that the citizenship of the Democratic Republic of Congo ranks lowest in the Quality of Nationality Index (which explores both external and internal factors, such as visa-free travel, the ability to move and work abroad, economic strength, human development, public peace).

“Ministry should be based on self-denial and self-sacrifice”

Now let us speak about Kolwezi and the Greek Orthodox mission in this city. Kolwezi is an industrial city. Nonferrous metals, along with uranium and radium are extracted here. Its population is about 400,000, and it is home to an airport and a railway.

The pioneering Orthodox missionary in Congo was the Greek Archimandrite Chrysostomos (Papasarantopoulos; 1903-1972) who came here in 1967. Although he was not young, he was fervent in spirit and had a gift of preaching, baptizing several dozen Congolese inhabitants. Unfortunately, several years later he contracted dysentery and passed away.

In the early 1970s the future Archimandrite Cosmas (Aslanidis; 1942-1989; then still a layman), who is nicknamed “the apostle of Zaire”, came here for the first time when he accompanied Fr. Amphilochios (Tsoukos), who afterwards became Archbishop of New Zealand and now serves as Metropolitan of Ghana. John Aslanidis, then a young man, undertook church-building activity in Congo, several years later returned to his native Greece, became a monk, and then came back to Kolwezi as a missionary and Hieromonk Cosmas of the Gregoriou Monastery on Mt. Athos. He built churches, preached, baptized, helped the poor, took care of the sick and prisoners. He made wooden beds for them by hand – they slept on cement floor before his arrival.

According to his spiritual children, Fr. Cosmas spoke brilliant Swahili, talked to peasants in their native language, and strove to do good every minute of his life. Whenever Fr. Cosmas went on a business trip, he always took a chain with him so that in case of need he could hitch a peasants’ wagon to his vehicle and help them deliver coal and sweet potatoes to Kolwezi. Through his tireless labors and fervent preaching, thousands of Congolese residents were converted to Orthodoxy.

Fr. Cosmas wrote prophetic words about the qualities of a true missionary: “His ministry should be genuine, with wholehearted devotion, based on self-denial and self-sacrifice, with a determination to leave your bones amongst those of local residents on the missionary field.”

The fearless ascetic more than once suffered from malaria and sunstrokes, and eventually died a tragic death: during one of his missionary journeys an oncoming truck slammed into his car on a desert road. A lot of money passed through the hands of this unmercenary, yet he died in utter poverty as a true monk. Some of his spiritual children believe that that collision did not happen by accident. So, the life of missionaries in this country is full of dangers.

The successor of “the apostle of Zaire” in Congo was Hieromonk Meletios who now serves as the Metropolitan of Katanga. There has been an Orthodox convent in Congo since 1987, and its first twelve nuns were Congolese. Nobody knows how many Orthodox Christians live in Congo today due to lack of reliable information – a civil war has been raging the country for years…

At last the sisters returned and we resumed our conversation. Nun Nectaria told me the following stories.

I dreamed of monastic life from my youth

—In the world I lived in Athens and had a successful career, working at one department of the Ministry of Economy. I heard a lot about the needs of African peoples so I joined an association of aid for Africa and spent much time in it. We would sew robes for the sacrament of Baptism, glue icons to wood, laminate tiny icons, send parcels with these chitons, icons, clothes and medicines to Africa.

I dreamed of monastic life from my youth. But my mother was sick and I never left her alone. I thought that my dreams of monastic life wouldn’t come true because I didn’t become a nun in my youth.

A prophecy of St. Porphyrios the Kapsokalyvite

—One day I came to the great elder Porphyrios the Kapsokalyvite (1906-1991), who was canonized several years ago. He was a wonderful man chosen by God from his mother’s womb.

As a boy of twelve, St. Porthyrios read the Life of St. John the Kalyvite and was so inspired by it that he went to Mt. Athos and led ascetic life there for some time. It was there that he became a ryasophore monk at a very young age. However, worn out by austere ascetic labors, St. Porthyrios had to leave Mt. Athos due to his poor health; but the great spiritual gifts that he possessed were so evident to people who communicated with him that St. Porthyrios was ordained a hieromonk at the early age of twenty.

From 1940 till 1973 Fr. Porthyrios served at the St. Gerasimos Church attached to an outpatients’ hospital near Omonoia Square in Athens. Through his prayers many patients were healed over those thirty-three years. The elder acquired the gifts of healing the human soul and clairvoyance. This is what Elder Paisios the Athonite used to say about the spiritual gifts of St. Porphyrios, “Father Porphyrios has got a ‘color television’, whereas I have a ‘monochrome’ one. The Lord sends people like him to this world only once every 200 years.”

In the early 1970s I came to Fr. Porthyrios for spiritual counsel. And he told me something that I couldn’t have expected. (I worked as an economist and still lived in the world). All of a sudden he said:

“Ah, such a huge, splendid and magnificent cathedral! It is like the Hagia Sophia Church at Constantinople! And you will serve in this cathedral as an acolyte!”

The construction of the Cathedral of St. Nectarios, one of the largest churches of Greece, hadn’t yet begun by that time. Its foundation stone was not laid until 1973, and the cathedral was opened in 1994.

When my mother passed away, I quit my job and came to the Cathedral of St. Nectarios on Aegina, and my obedience was to serve as an acolyte at this huge, splendid and magnificent cathedral. Elder Porthyrios had seen me in that cathedral some twenty-five years before his prophecy was fulfilled!

On how Divine providence brought me to Congo

—Nothing happens in our lives outside providence of the Lord. And this providence brought me to Kolwezi. My father-confessor (he was from the Gregoriou Monastery on Mt. Athos) was aware of my desire to serve the peoples of Africa. Providentially my spiritual father and His Beatitude Theodoros II, Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and All Africa, were on a visit to Aegina at the same time. They spoke about me and my cherished ambition, and the patriarch blessed me to participate in the Orthodox mission to Kolwezi.

Did I think about dangers? To my mind, when you resolve to do something for the good of the Church you don’t think about dangers.

The mission to Kolwezi

—Upon my arrival to Kolwezi I met several members of the Greek diocesan Orthodox mission there, namely Metropolitan Meletios of Katanga, one monk, one Greek nun, and a ninety-year-old Greek widow who still felt very fit (she had served in the mission for many years).

There is an Orthodox monastery nearby. Its abbot is a Greek from Mt. Athos, the community consists of eight ryasophore monks and all of them are native Africans. They have built a church in honor of the Holy Apostles, they cultivate the land, and grow vegetables. They even keep goats. I visited this monastery, it is twenty minutes’ journey from Kolwezi. The diocese supports the monastery, and the monastery helps the diocese. There is also a convent in Congo. Its sisterhood consists of five African nuns; its abbess once lived in convents on Crete for two years.

Metropolitan Meletios is the father confessor of these monastic communities; he gives spiritual guidance to the monks and nuns. New novices often come to both communities seeking monastic life, but not all of them are admitted to the communities. It may take the lifespan of a whole generation until Africans come to understand the true meaning of monastic life and monastic vows.

In the diocese we would bake cornmeal bread for workers, priests, an orphanage, and both monastic communities. I prepared catechumens for Baptism, taught Orthodox catechism to children and women, and was in charge of many practical things, such as the storeroom (pantry) and kitchen, and baked various treats. Each church would send at least one representative to the diocese for catechizing; first we trained them, and then they would return to their villages and take up the work of catechizing there. We mostly communicated in French as the Congolese speak this language. We also had a Greek school so that people could read the Gospel in Greek.

There are 140 Orthodox churches and seventy Orthodox (native African) priests in South Congo, and all of them are under the jurisdiction of our metropolitan. Seminars are held for the clergy every July. A school is attached to each of our churches. Our priests usually teach at schools as well. Our missionary center has five schools, namely an elementary school, a high school, a junior high school, a sewing school for girls, an agricultural college, and a school for illiterate adults.

A lot of time and patience are needed

—Africans are keen to learn more about Orthodoxy. They realize that their culture is based on magic; they want to abandon these practices and are afraid of them. They have learned that magic is powerless in the Orthodox Church and they want to join this Church in order to protect themselves against this witchcraft. Many of them prefer to receive the sacrament of Baptism.

The problem is that Africans are easily converted to faith and easily drift away from it… They have neither an Orthodox tradition nor Orthodox education. Therefore, it is difficult for them to comprehend the depth and richness of Orthodoxy. Their spiritual development and growth are very slow. A lot of time and patience are needed.

Another serious problem is the poverty of Africans, many of whom live in utter misery. They wait for humanitarian aid (containers with clothes, shoes, and drugs) from Greece all the time. And Greece has been helping them despite the financial crisis. Today Greeks donate more generously than ever. The basement of our convent has loads of things for shipment to Africa.

The missionary tradition has existed in Greece for many centuries since the Byzantine Empire.

Is life in Kolwezi difficult?

The climate in Kolwezi is quite “challenging,” with very similar temperatures in summer and winter – about +25 degrees Celsius. Since Kolwezi stands in the mountains, it is cooler here than at the base. Though we have a lot of sunshine, it is not too hot in this city; the temperatures seldom rise above thirty degrees. We normally have six-month periods of drought and six-month periods of rainfalls. During drought strong storm winds raise dense masses of dust into the air and carry them. Clouds of dust are hard to endure, yet we do manage to survive.

The joys and sorrows

The greatest joy is to see healthy, happy children who make the sign of the cross and pray. In this respect they are different from our Greek children: our children begin to fidget, “twist and turn” after fifteen minutes in church, while African children sit down on the steps closer to the sanctuary – they sit quietly and motionless through the Liturgy without any pranks.

What makes me really sad is seeing sick people, especially sick children. Malaria is the most prevalent disease in the country and it affects very many children. Severe malaria causes dehydration, and they die. There are no drugs in villages, and their inhabitants often cannot reach the nearest city before it is too late. Since there are too few (if any) cars in villages, people often rent motorcycles to get to the nearest town or center, but many residents have no money to pay for the rent…

Purity of soul is what really matters

—I liked native Africans – they are quiet, simple people. They always try to avoid conflicts and not to offend anybody because an offended person can turn to a sorcerer.

They are very impressed by the technology of white people, while we want them to be more impressed by the spiritual depth of Orthodoxy.

It is better to speak with Africans in the same way we speak with children. If you start talking with them about serious things, it will be very difficult for them to listen to you. This applies to adults too.

Sometimes they said this to me during our talks:

“You white people will be saved, while we, black people, won’t be saved.”

And I would answer them:

“One’s skin color doesn’t matter. What really matters is the purity of your soul, which glorifies God.”