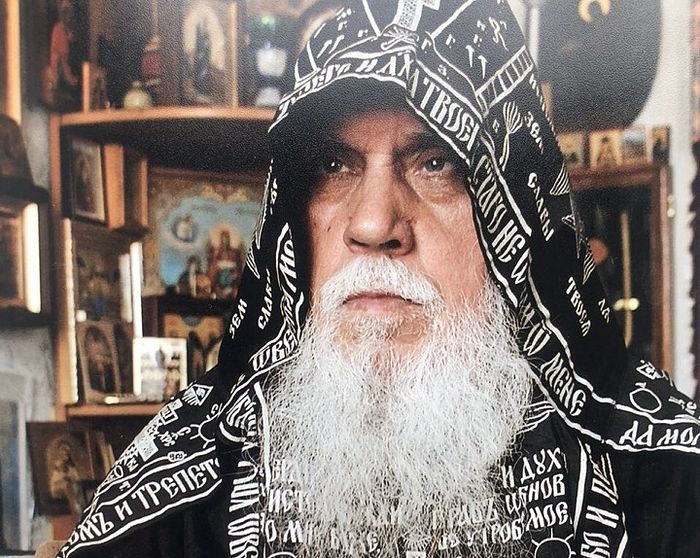

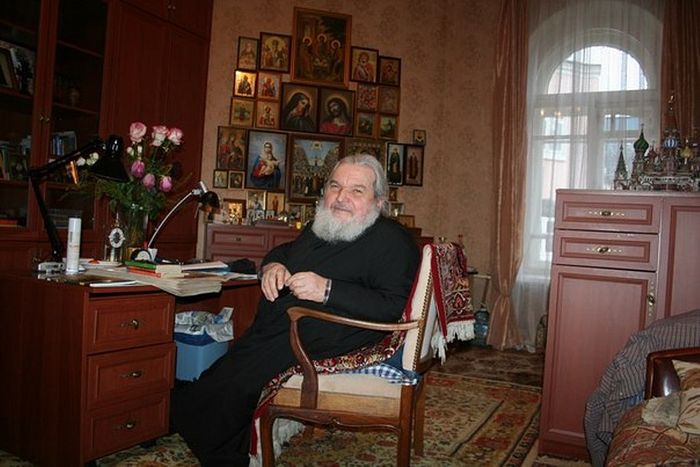

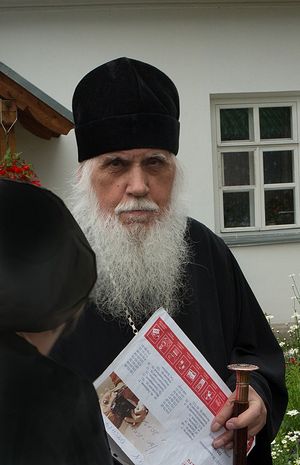

The beloved Russian elder Schema-Archimandrite Tikhon (Murtazov) recently reposed on May 24/June 9. His fortieth day memorial on July 5/18 coincided with the uncovering of the relics of St. Sergius of Radonezh, who appeared to the elder in his youth.

In his youth, in a small Tatar village on the Sheshma River, where there was no longer any church (it was destroyed in 1935 at the same time as the future schema-archimandrite’s appearance into the world) and there were no monasteries, one evening, when all the young people had run off to the dance and he was also swept away by the happy crowd, Alexander Murtazov suddenly saw an elder on the bridge… It was a monk, as the one beholding him later learned, and his strange clothing was a monastic schema.

Time stopped.

“Are you going there, Alexander?!” the monk who had appeared suddenly asked with reproach.

The future schema-archimandrite stopped, and didn’t take another step towards the dance.

He later said, “When I arrived to enter the Moscow Theological Academy at Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, I saw this monk in an icon! It was St. Sergius of Radonezh!”

Batiushka diligently read the akathist to him throughout his whole life in gratitude for placing him on his path in life.

We are here publishing new memories of this recently-reposed elder.

“What will this boy become?”

Hierodeacon Nikon (Murtazov), brother of Schema-Archimandrite Tikhon, cleric of St. John’s Monastery in St. Petersburg:

Fr. Tikhon was born in 1935 in a peasant family in Tatarstan. Our father, Ivan Feodorovich, was a tractor driver. Our mother, Daria Matveevna, was a housekeeper while our father was still alive. Both of our parents were deeply-believing people.

As soon as the war began, our father, as a private farmer who hadn’t joined the collective farm, was called to the front.

“What kind of soldier am I?” our father reasoned, who retained less than thirty percent of his vision after going through smallpox in his childhood. “They’ll kill me, and that’ll be it!”

And that’s what happened. He was killed in the first year. When he left for the front, he took little seven-year-old Sasha by the hand and walked with him to the outskirts and said goodbye.

Then, in our day, Batiushka often spoke with Fr. Adrian (Kirsanov) from Pechory about how the war was inflicted upon the people for apostasy. “We must pray, or there will be another war,” they warned. They even specified that if this one were to begin in June, then the next one would suddenly begin in July, but of which year depends on our repentance.

Left a widow with three children, our mother worked as a commissioner for agricultural preparations for the front, a supply manager in the hospital, and a forest ranger. Sasha (Schema-Archimandrite Tikhon’s name before his tonsure) always helped her with her work, especially since she hadn’t been able to study in her time. “What reading? There’s too much work,” the old men insisted then. When the forest was sold, it required stamping all the trees, and marking all their numbers on a registration card—my brother did all of this for her.

Our mother was lively by nature. She jumps on a horse, gun over her shoulder, and she’s off! If she saw any violations, she didn’t especially punish anyone. “Look at me!” she would say strictly. “Now go hide that stump!” she would say, and ride on further.

She was merciful, although, she raised us strictly—she ruled with an iron fist, you could say. Sasha especially got it. I was very sick from childhood and was constantly either being treated in hospitals or living with my grandmother.

Sasha was humble from childhood. Sometimes, some drunk villager would go to our mother’s work hut, carry something off, and Sasha would be punished. But he never denied it, never justified himself.

“Beat me if I’m guilty,” is all he would say to our mother, immediately adding, “Forgive me.”

He was on the ball; he was clever. Once, when our mother was away, a wolf snuck through the fence… Babushka Martha Vasilievna ran out throwing logs at it, and it seized our dog in its teeth and tried to jump over the fence with him. Then Sasha went out with a gun, took aim, and the wolf got scared and ran away. But he didn’t even have any bullets! He wasn’t even scared; he bravely walked out towards the beast.

He always took it upon himself to defend someone or to help the weak. If one of the elderly had to get his pension, but being illiterate couldn’t understand the papers, he would always run to fill out everything himself and bring it back to them. He was trusted unconditionally.

The old ladies especially loved him because he would gather them all in prayer. There was a woman from Biryulevo living in the village then. She had a Gospel at her house. Little Sasha could read the Gospel in Church Slavonic to the gathered women all night long. “What will this boy become?” the old-timers marveled.

He knew many prayers by heart from childhood: “Our Father,” “Rejoice, Virgin Theotokos,” the Creed, the Psalms.

Numerous testimonies to the power of prayer were preserved in our family tradition. Our grandmother on our father’s side, Martha Vasilievna, was very devout. She had many children, but they all died in infancy. When John, our father, was born, she went to the Church of the She Who is Quick to Hear” Icon of the Mother of God, not yet ruined at that time, ordered a moleben for the blessing of water, and sprinkled the infant—and the Lord saved him.

They lost a calf in my mother’s family when she was still young. They sent her to find it. “Go pray!” they said, “and don’t return until you find it.” She stood on the spot where she last saw the calf and began to sing: “Let my prayer arise (our mother was illiterate and she memorized prayers by heart, but didn’t know how to sing them correctly, and she messed up some of the words), in Thy sight as incense, and let the lifting up of my hands, be an evening sacrifice…”

She had just finished the prayer when a “mooooo” was let out. The calf, it turns out, had fallen into a silage pit, and grass had fallen on him and covered him. Everyone was looking for it for three days but couldn’t find it. But Mama prayed, and God’s creature responded to her prayer.

Once when our mother was already a forest ranger, the forest was on fire.

“O Mother of God!” she begged. “I’ll be sent to prison…” when from out of nowhere came a little cloud and poured all its rain precisely on the spot where the flames were blazing.

There were many such miracules.

The following thing later happened with Fr. Gergmogen when he went to the Holy Land for the first time, and went to the Jordan River. They stood on the dry shore and he and Fr. Guri (now Bartholomew in the schema) began serving a moleben , when suddenly the water began to stir! So much so that all the steps were wet. But Batiushka never attributed this or any other miracle to the power of his prayer—after all, Fr. Guri was standing there and praying as well…

This is the kind of upbringing he had from childhood—humility and in obedience. Mama also tried not to take any drastic measures, and so she didn’t fancy herself to be anything special. After all, obedience safeguards one from pride.

One day she was busy doing some housekeeping at her ranger station when there was a knock at the door. She opened, and there stood someone tattered and torn. Mama was not timid and started asking him who he was, where he was from… He turned out to be an arrested priest who had been released from exile, and he was going home on foot. Our mother let him in and sat him at the table. As she was asking him about confession, she closed the door, and people began to gather outside from out of nowhere. The enemy also hinders whatever contributes to the salvation of the soul. Trucks suddenly began to approach.

“Give us some wood!” the furious villagers were yelling. “We defended the country. We deserve it!”

Then the priest said to her, “Daughter, leave the forest. It’s not women’s work. You see: They come with guns…”

My brother couldn’t help our mother anymore; they called him to the army. He served in Baku in the artillery. Our mother then sold our grandmother’s house in the village, and we relocated to the only open church in the region, in Chistopol. They didn’t have any singers there, and our mother had a good voice.

Fr. John was serving there—one of the repentant renovationists. There were also several nuns from closed monasteries laboring at the church; they used to help take care of Patriarch Sergei (Stragorodsky)’s residence. There was a clairvoyant eldress, Anna Mikhailova, there. They all took care of Alexander together as he was preparing for seminary; they taught him to read at the services and sing on the kliros.

In sanitoriums, where I used to go for treatment from childhood, I picked up some ideological rationales—they were really inculcating the youth then. Once I even wrote a letter to my brother at seminary: “I’ll be right back; you and I are going to reeducate mom” (it was about how she was too much of a believer). He gave me quite an earful!

He himself was very strong in faith from childhood.

Always in prayer

Archpriest Michal Melchik, confessor of the Pskov Diocese:

When I was elected to the Diocesan Assembly in 1998 to confess the clergy of the diocese, I rushed to Vladyka Eusebius: “Vladyka, perhaps I don’t have enough experience…” “Go and gain some experience,” he replied.

“Where will I go?” I thought. I ran to Fr. John (Krestiankin), but he couldn’t receive me at that time because he was already weak and sick. He gave me a brochure describing various circumstances in life: If you lose your money, if you have housing problems, and so on. Then I saw written there: If you have been chosen for some position for which it seems you don’t have enough strength—neither spiritual nor physical… And all around was added, “It was from Me.” I read it, and I had a river of tears. I couldn’t calm down: “Could they really not find anyone better than me?” They chose me. June 23 this year marks twenty years of my service.

And after Fr. John, I went to see Fr. Germogen (Murtazov). He had gained experience. Next year, if I’m still alive, I’ll have been a priest for fifty years.

I was already a priest for about thirty years when a brother priest came to me for confession and my knees were shaking. Fr. Germogen was already a spiritual father then, and he would confess the bishops. Then, throughout all those years, in the most difficult cases, I would turn to him for advice.

I remember, at first I asked him, “Batiushka, priests have their own weaknesses. What canons should I appoint for them to read?” “You don’t need to burden priests with canons because we are always praying!”

So merciful!

He himself really did always abide in prayer. “To pray for people,” he said, recalling the words of St. Silouan the Athonite, “is to shed blood.” He didn’t give out penances, but imposed prayerful podvigs upon himself for others, entreating for those who had stumbled. Of course, people were grateful to him and felt his help.

As far as prayer went, he always had concrete recommendations. For example, people always ask priests in church: “How should we pray for someone who has died who didn’t confess and commune?” I passed this question on to Fr. Germogen, and he answered, “You have to read the Psalter for a year for such a person, and then you can order the forty days Liturgy for him. You can’t order it right away. How can you take out a particle [of the prosphora at the Proskimdia.—Trans.] for him if he died unrepentant?”

Archimandrite Germogen labored greatly in prayer.

He never broke a man

Archpriest Dionysiy Astakhov, cleric of the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Kolpino, St. Petersburg Metropolitanate:

I used to go to see Fr. Nikolai Guryanov, and I stayed at Snetogorsk Monastery. Matushka Lyudmila (Banina) welcomed me, and I served there sometimes. When I first wound up at the monastery, she told me to go get a blessing from their spiritual father. I knocked and he let me in and sat me across from himself. “Where are you from?” “Tsarskoe Selo,” I said. “Oh, a tsar,” Batiushka joked.

He asked me about something else too, but I didn’t attach any special significance to our conversation then. “A good old priest,” I thought.

I went again, and Batiushka was walking around the monastery angry, yelling at the workers. I was walking behind him, but he wasn’t paying attention. There was another woman hanging around him, and Batiushka turned around and chastised her: “What did you come here for?! You have Fr. John Mironov in St. Petersburg!”

I myself am from St. Petersburg… Nevertheless, I didn’t lag behind the elder—I already felt that he had been made wise by the Lord, and I had one issue that really needed to be resolved. Fr. Germogen then proceeded into the altar and came out just as formidable. “Sit here!!” he said, pointing to a bench. “Uh oh,” I thought, “I’m in trouble.”

Then all those clouds on his horizon suddenly dissipated somewhere, all the thunderstorms calmed, and the lightning no longer flashed! And for half an hour, he spoke with me in the most peaceful manner in all the fullness of his usual affectionate way, penetrating into and helping with everything.

Perhaps that’s how Batiushka checked people. He would ask, “What did you come for?” and if the person doesn’t really need him, he would leave.

I once sat under Batiushka’s window for two days. They tried to chase me away, but I waited. However, I left then because Batiushka was sick. But then about a month later, he confidentially told me with a smile, “I remember how you were on guard here for two days!”

Later I went to Batiushka for confession quite often. You tremble on the way there: “How can I tell him that?!” but you arrive, and Batiushka could put you in the right frame of mind, sometimes even telling a joke so that you wouldn’t even notice how you were baring your soul to him—what a load is removed from your soul! Glory to God! And you flutter away as if on wings.

Batiushka really loved the services—he wanted the Liturgy to be served as often as possible. During certain important periods for him, he would bless me to serve the daily cycle in his home church.

Even when I wasn’t able to speak with Batiushka, it was still instructive and gratifying just to watch how he patiently heard people out. We young priests can sometimes rush some women: “Alright, get to the point already; enough babbling…” But he listened; he never rushed anyone. His ministry was entirely sacrificial. He only slept a little. He would rather restrain himself in something than deny someone else.

He prayed a lot. Just to see him at prayer was already a serious schooling: how he called on the Lord with such deep feeling, pronouncing some phrases several times. He really valued the Jesus Prayer. Sometimes we’re biased against Greek monasteries: They’re Greeks, and we have our own traditions. But Batiushka revered their way of monastic life because the continuity of mental activity was never broken in Greek monasteries. I went to Greece often, including to visit convents there—Fr. Germogen would then always very attentively ask me about everything.

Batiushka never broke a man. For example, when I went to Athos in the 1990s, I started wearing a Greek skufia. Oh, how people tormented me about it! “What on earth are you wearing?! That’s not Russian…” But Batiushka received everyone as they were. You love Greece? Great! I remember when the abbess decided to reeducate me: “What is this, Fr. Dionysiy? Are you serving the Greek way? What, are we Greece?!” “We have here … our own Greece!” he said, finding a way to defuse the tension.

No matter what sin you came to him with, he never pounced on you with rebukes. He’d more likely sigh with pain. He covered everything with his love and prayer.

“You have to read the Gospels,” he would instruct, “both for others and for yourself.”

One of my spiritual children was struggling with alcohol addiction: “Sooner or later the Gospel will pull you out,” Batiushka told her, blessing her for this spiritual work.

She later told me what happened. There was a moment thanks to which she turned away from drinking. She saw in in a dream that she was standing, holding a can of beer, and watching: Batiushka was coming… He was so angry, he snatched the can out of her hand and crumpled and trampled it: “That can will drag you to hell!”

It had an effect on her.

Batiushka lived constantly in love.

If Batiushka loves us so much, then how much must the Lord love us!

Schemanun Olga (Diakonova), nun of Snetogorsk Monastery:

A great sorrow led me to the Church in the early 1990s—I lost my twenty-seven-year-old son. I was searching for, as it was then said, “a method by which it would be possible to help the untimely deceased.” So I wound up in Pechory. Batiushka John (Krestiankin) was sick and couldn’t see me then.

“There’s a spiritual batiushka in the Church of the Great Martyr Barbara. Go see him,” someone advised me.

So I went. Fr. Germogen had been serving in that church for a while then. He was the first priest to speak to me in detail, but they were most simple and understandable words about the salvation of the soul. He gave me two hours of his time! He has remained a personification of love in my memory. “If Batiushka loves us so much,” I later often thought when I was already tonsured by him in monasticism, and then in the schema, “then how much must the Lord love us!”

Batiushka constantly instructed us to read the Gospels. He would tell us, nuns and schemanuns: “At least twelve chapters a day!” and then say about himself, “People come to me, and I answer them. They return later: ‘Batiushka! Everything turned out just as you said!’ But that’s if I managed to read the Gospel before we met. But if wasn’t able to read at least a few chapters, and I received people, I would answer them from my spiritual experience—but then there were mistakes…”

“Batiushka, my feet hurt,” someone complained to him once. “I can’t read the Gospels standing up.” He blessed to read it sitting down too, if you had an ailment. And he blessed us to pray thus: “Even if you’re lying down, even if you’re sitting, even if you’re upside down—just pray!”

That is how one servant of God recently remembered Batiushka. She has sore joints, and if she goes for a walk her legs ache, and she haves to lie on her bed with her feet up on the headboard. She lays there and prays. And suddenly it dawned on her: “It’s like Batiushka told us: ‘Even if you’re upside down, pray!’”

“Batiushka!” I said one day, amazed at his kindness. “Why don’t you refuse anyone? You bless whatever they ask of you.” “We’re in difficult times now,” he said. “It’s better to sin by love than by strictness.”

I can’t even remember a time when anyone departed from him disappointed. Sometimes we even resented it: Batiushka would be feeling ill, and suddenly someone shows up, asking directly and impudently, “Where’s your elder here?!” But Batiushka saw in the spirit that it was a man weak in soul—maybe he’d never go see a priest again; and he could stand with such people, despite how he was feeling and the man’s bad behavior, talking with them for several hours, gently instructing and comforting them.

Batiushka saw and felt a lot of things in the spirit. I remember one time how the cows at the farmstead started dying. They asked Batiushka about it, and he said, “It’s because you have the demon of fornication there.” They started investigating. The workers there lived in a trailer, and one of the laywomen volunteered to bring them food. That’s where the lasciviousness was going on. As soon as everything stopped, the cows stopped dying.

Another time Batiushka was at one of his spiritual children’s houses. He went to the bathroom and came out saying, “Why do you have the demon of fornication there?” They had to explain that they had a neighbor on the other side of the wall who brought someone new home almost every night.

Batiushka could see and drive out impure forces. Sometimes he would directly chase out some invisible being: “Go away! Go away!”

He could heal with but a touch. One time I had a headache; I was kneeling in church, leaning against a stool, and Batiushka walked past me and gave me a whack on the head! I didn’t even have time to think before I felt the pain go away!

Batiushka was love itself.

How to earn a share of the Kingdom of Heaven

Hieromonk Methodius (Zinkovsky), cleric of the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God in Vyritsa, candidate of technical sciences and candidate of theology:

My twin brother Fr. Kirill and I started going to see Fr. Nikolai Guryanov in 1993, and he always blessed us to go to Snetogorsk Monastery to Fr. Germogen and Mother Lyudmila. We would work in the monastery both in the summer and in the winter. As soon as we had a break from seminary, we would immediately go there.

Fr. Germogen encouraged us in our obediences: “Earn your share,” he would say, meaning the Kingdom of Heaven.

Our spiritual father was Fr. John Mironov from St. Petesrburg, but Fr. Germogen was also an invaluable spiritual guide and even, one might dare to say, a friend. Of course, we knew that many bishops came to him for pastoral care, but he was an incredibly tactful and sensitive person and behaved with us youths just like a friend—although he had the authority to behave completely differently.

Thank God, Archimandrite Germogen lived a long life. He reposed, as was foretold to him by Blessed Ekaterina of Pukhtitsa, who was glorified this year, in the eighty-third year of his life. He told practically no one about this prophecy he had received at the beginning of his pastoral path. He tried not to create any excitement around himself, only praying and laboring until the end. But, as we know now, he knew when he would depart. The Lord revealed it to him.

Archimandrite Germogen was for all of us a man who connects generations. He knew many who had gone into exile and to camps and spoke with podvizhniks [men or women who labor ascetically in the religious life—Trans.] who are now canonized. In his experience, the Russian Church tradition was not broken, and he introduced us, the new generations of Christians, to it.