The director of the Serbian-Russian school in Belgrade Boško Kozarski speaks concerning these difficult times for Serbs, about the correct approach for studying history, and the paradoxes of real hope in Christ.

This is an all too common report in the Serbian media these days:

“During a time of pilgrimage to holy sites in Kosovo and Metohija1, two buses of Orthodox people were assaulted with stones in a neighborhood of the city of Pec. A group of Albanians laid in wait for the return of pilgrims after their visit to the Church of the Theotokos of Kvostanska2 and a moleben, which was served by Father Nebojša from the city of Istok. Offensive screams, gestures, and stones—this is how the Albanians greeted a group of pilgrims. There were no casualties, the transport vehicles suffered material damage. The police are investigating.”

This came to pass not long ago, around the second half of October. I reiterate, this report is nothing out of the ordinary, not unprecedented; no, this is an ordinary picture of events, in which there is nothing surprising. Pilgrims go to Kosovo to pray, they are met there with stones and insults, and the police promise “to conduct a thorough investigation and identify the perpetrators.”

In the group of pilgrims who traveled from Belgrade was Boško3 Kozarski, director of the First Russian international school in honor of cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova in Belgrade. Concerning the recently opened school itself, and the interest of Serbs to study the Russian language and culture, there will be a separate huge discussion; but now—here is a conversation with Boško about the disturbing realities of the everyday life, which Orthodox brothers and sisters in Serbia live through.

—Boško, you often travel from Belgrade to Kosovo and Metohija. Most often not alone, but together with friends and coworkers. The road from Belgrade to Kosovo is a long distance by Serbian standards. Why would a resident of the capital go to a province, and especially one that is so “problematic”, and frankly untranquil, like Kosovo and Metohija? I know from my experience that many Serbs, especially from Belgrade, don’t feel very much for Kosovo, believing it is better to bid farewell to it, and to join the “civilized European family” as quickly as possible.

—Every person possesses his own path in life, and often this path leads him far from native home and hearth. But if a person has not lost his feelings of the Motherland, he always feels an ardent desire to return more and more to his origins, to the place where he was born, grew up, and first spoke the words “mama” and “daddy”. A Motherland45—it is like a pure, clear fountain, quenching the thirst for light, the thirst for God, so to speak.

That’s if you’re taking a single individual into account; but what if we take our entire nation? In my deep conviction, such a motherland like this, for Serbs, has proven to be Kosovo and Metohija. It was here we first came to light as a nation. Here we became Christians, grew up and strengthened.

In such a light, the desire of the Serbs who have not forgotten their spiritual motherland to come and worship in the holy sites of their native land is completely natural—even if their native land is now under occupation. An analogy can be drawn with Jerusalem—people went to a city occupied by the Romans for prayer. And the Holy Family, I remember, did not see any obstacles in it. Why can we Orthodox not follow their example? And so, we do.

—You are the head of the Serbian-Russian school in Belgrade. Do your trips to Kosovo possess an educational purpose?

—To be sure! During each of my trips to Kosovo and Metohija, I try to take new members, if it is not too dangerous, of course. In any case, during the pilgrimage, I take a lot of pictures, sketches, and records, which I then bring to the attention of the readers and subscribers of my pages on various social networks. Of course, we tell a lot about our pilgrimages to schoolchildren of different ages, who, by the way, are very jealous of those who got to go.

We arrange a meeting after the trips, and we show pictures and videos at school, they sit with their eyes wide open, teeth clenched, and they almost cry: “We want to go too! When can we?”

Even such tears are joyful; it means that children, and not only children, are not indifferent; they don’t choose to simply not give a second thought about their own history. They, albeit latently, all still feel the spiritual significance of Kosovo and Metohija for them. Seeing such care—the opposite of indifference—I could not refuse the dozens of new acquaintances who ask to come on every new trip.

At first, perhaps they are guided by a simple interest in traveling, spending a few school days away from usual life; but then I observe that the overwhelming majority are beginning to see: the Visoki Dečani, Gračanica, Kosovo Field, the Patriarchal Monastery of Peć, here it is—the motherland. You can see it in their eyes. There eyes are growing wiser, becoming more serious. It is comforting.

—How long have you been in Kosovo and Metohija? Where do you go there?

—A pilgrimage usually lasts three days, from Friday to Sunday. We definitely visit the brothers and sisters living in enclaves, and certainly the holy sites too—it’s a must. We spend several hours in Velika Hoča and Orahovac—there we can rest for about six hours, and then we journey to the main goal of our travels—the Visoki Dečani monastery, where there will be a Liturgy. After the service, we try to visit the holy sites of Metohija, the southern part of the province, which even now, alas, is in great danger. Then, we return to central Serbia, to Belgrade.

—With whom do you keep company, when traveling to Kosovo?

—First of all with self-sacrificing brothers, who in spite of everything remain to live in this land6, even after the war, pogroms, and constant provocations. We keep company with the Priests and monks, who, being good shepherds of Christ, take care of the Orthodox in this land. From conversations with them, our pilgrims learn how they struggle. And it is a struggle, because to call it “life”, by our understanding is extremely difficult.

We are spoiled, do you understand? And too seduced by the lies of the media. And there, in our true motherland, everything is so real. A couple of weeks ago, they felt what everyday life looks like in Kosovo and Metohija. When we were going to Little Studenica Hvostanska monastery7, near the village of Vrelo, not far from Peć, we were attacked by a group of Albanians throwing stones and shouting vile insults, etc.

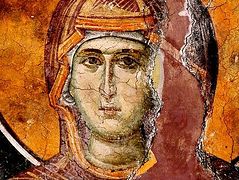

No one was hurt, thanks to the intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos, to whom we prayed before boarding the buses. The driver shouted to get down, or rather, to hit the floor… according to the local priest, such cases are nothing special. It’s the daily “routine” of those who remain or have the courage to return to the native lands of Serbian Orthodox Christians.

—Is it true that the number of Serbs living in Kosovo and Metohija is decreasing? What do young Serbs from Kosovo think? Do they want to leave? To where? Do they have any prospects in Kosovo?

—From a certain point of view, you know, the “capitalist” one, which is now being forced upon us, the prospects for Serbs in Kosovo are zero. From any other point of view—economics, politics, or anything else—it’s the same thing. It would seem that everything is lost, we cannot do anything… it’s terrible, horrible, disastrous! But as practice has shown, and history has proven more than once, there is still prayer. It gives hope.

There is a sad, but still hope-giving saying of one modern Serbian bard: “When all is lost, everything is still not lost”—this is about us Orthodox. Kosovo again and again helps us return to faith in the resurrection of Christ, in the hope of the seemingly hopeless. If God is with us—who is against us?

So one thing remains for us: to be with Christ. And everything else will follow, is it not so? And gradually, still quietly, but persistently, the good old Serbian cry will begin to sound: “See you in Prizren!8” The small Serbian enclaves in Serbian land—these are the seeds of a future rebirth. I believe in that. What people can’t do, God can.

—Hostility towards Serbs still continues. What causes it, in your opinion?

—The region of Kosovo consists of two parts: Kosovo [proper] and Metohija. So in the northern part, in Kosovo proper, the situation is slightly better than in the south, in Metohija. If, say in Pristina, or in large cities like Prizren, we can walk freely and safely through the streets, sit in cafes, speak Serbian, then in other places, especially in the south and in small towns and villages, it isn’t possible. You will always stumble on, let’s put it gently, “the negative reaction of the local population.” A walk, a journey through Metohija outside protected objects, holy sites of the region, can end very, very sadly, believe me, it is so.

—Yes, I know, I have traveled there. Since then, they won’t let you. All right then, but what of the Serbs in Metohija?

—What is a bird in a cage? And not even a gold one! This is to speak of the Serbs there. Despite all the sweet assurances that “independent Kosovo is moving in great strides” towards some kind of “Europe” and its values, these “movements” are not confirmed in life. Nor are these “values”. And those brothers and sisters who continue to live in Kosovo—these are real Bogatyrs9 [heroes] in Spirit. They are truly leading the battle—the battle for the preservation of the Serbian name in Kosovo and Metohija, of Orthodoxy in this region.10

—Is there a danger for Orthodox holy sites in Kosovo? Do attacks on churches and monasteries continue? Are there any provocations? If so, why?

—The very presence of representatives of the Kosovo Force (KFOR)11, in Visoki Dečani monastery for example, and in enclaves proves that Orthodox holy sites and Orthodox people themselves are under threat here. The recent past is illustrative: the fate of the destroyed and desecrated churches and monasteries, and those expelled from their homes would have been shared by the rest if there were no KFOR troops.

The desecration of churches is no longer a matter of particular interest, and arson and destruction—this we all saw during the pogrom of 2004—when, by the way, our international “defenders” did not help us. But again, faith in the Resurrection is not dead. Zočište Monastery which was raised to its foundation is now restored and shines even brighter than before. It gives strength, and strengthens the belief that our struggle and persistence has a purpose. That all is not lost, remembering the words of our bard in general.

—Does it make sense to continue to travel to Kosovo and Metohija, despite the difficulties?

—It not only “makes sense”—we simply must visit Kosovo and Metohija more and more often, keep in touch with the brothers, and teach our own spiritual history. If we stop going there, I fully admit that Kosovo Serbs will feel betrayed, abandoned, and powerless in opposing temptation of all kinds. The last embers of fire will go out, we would renounce our name. Thirty years is enough for Serbs in Kosovo and Metohija (once the Serbian Fatherland) to be remembered with a contemptuous smile in the “right” museum. In a way, we are nstupid and unworthy of a great nation, if we consider ourselves as such. So, I will persistently make similar trips whether it’s with acquaintances new or old, from Belgrade, or our other people from Niš, Subotica, Kraljevo…

—By the way, if pilgrims were to come from Russia, would that be good?

—In my opinion, very good. Only, in the situation of Kosovo and Metohija, it is necessary to take into account the realities there, and to follow safety rules. In the rest of Serbia, it is without difficulties, but there in the “Serbian Jerusalem” [i.e. In Kosovo], there must be the upmost attention and caution. But the support from the brothers would be huge, believe me. The Serbs appreciate that, and remember.

It is necessary, in my opinion, to stand on the land of Kosovo, to feel it, and to venerate the relics of the Holy Tsar Stefan Dečanski, to pray before the icon of the Theotokos in Visoki Dečani monastery, which I must say, unites our peoples. We must pray at Kosovo’s holy sites—there lies our real history and reality, this is our real historical and spiritual education. What kind of Serbs would we be without Christ, without Kosovo and Metohija? Indeed—we would not be Serbs at all. And we really desire to remain an Orthodox people, remembering our family12—both by blood and spiritually.

relic pagan culture in some places, indeed Balkans have the worse haunted quality and a witch from the west felt the atmosphere in Belgrade was very witchy, she liked it! wake up! and what of the hypocrisy of Bosnian serbs who used prostitutes who were coerced, the doctor who documented a lot of rapes by serbs was serb himself so where is the bias and lies? why was city renamed velesz (theslavdevil) mid 20th