The parable of the Good Samaritan is well known to many of us from childhood. It is customary to think that we know it well. But do we? On the face of it, we sort of know it. But really, it is only possible to spiritually know some parable, some teaching of Christ when His words become a rule of life for us.

Christ uttered the parable of the Good Samaritan as an answer to a lawyer's question about what he should do in order to receive eternal life. All Jews knew the answer to this question, which was already given by God in the Old Testament - in the books of Deuteronomy (6:5) and Leviticus (19:18). The answer lies in love toward God and neighbor. Christ makes the lawyer answer his own question aloud. The Saviour confirms the correctness of the answer and adds: This do, and thou shalt live (Luke 10:28).

The lawyer is not satisfied with the answer. He asks: "Who is my neighbor?" At that time, the question arose as to whom one should consider to be a neighbor. The lawyers considered only Jews to be their neighbors; the Pharisees considered as their neighbors only such men who were as righteous as they considered themselves to be, and all others they considered to be sinners (as we saw in the parable of the Publican and the Pharisee), and that is why they did not acknowledge them as neighbors. The Lord Jesus Christ introduced an essential complement to this moral law of the Old Testament. Jesus Christ explains to the scribe just whom one should consider to be one's neighbor by the parable of the Good Samaritan, which the Evangelist Luke has preserved for us:

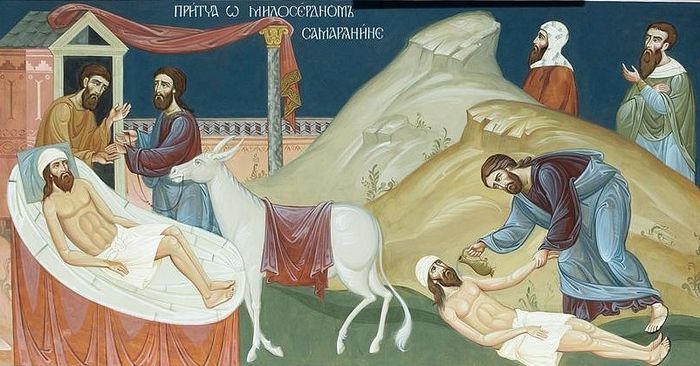

A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, which stripped him of his raiment, and wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead. And by chance there came down a certain priest that way: and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. And likewise a Levite, when he was at the place, came and looked on him, and passed by on the other side. But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was: and when he saw him, he had compassion on him, and went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee. Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves? And he said, He that shewed mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go, and do thou likewise (Luke 10:30-37).

The Samaritans and Jews were at enmity with one another on the basis of religion. A Samaritan was for a Jew a man unclean and despicable. But the Samaritan knows better that in the performance of works of mercy there is no distinction between men.

According to the Gospel, every man is a "neighbor", irrespective of his race, tribe or convictions. A "neighbor" for a Russian is not only a Russian, or for an American, an American, and so forth; that is, not only a like-minded person, not only a colleague and not only a fellow countryman. A neighbor for us may prove to be also our public, political enemy, our ideological opponent, a man who does not agree with us on religious and other questions, a man who is psychologically and physically alien to us and even offensive.

Every man is a "neighbor" - whether he is one of our own or a stranger. Love for one's "own" must not fill up our whole heart to such an extent that no place remains in it for showing consideration to "strangers". The parable of the Good Samaritan, as also the whole Gospel, erases the boundaries between our notions of who is "near" and who is "far". For God, no one is far. For God, all men are near, all are his precious creations

Few there are who can love everyone equally; but we can engender in our hearts a new consciousness of the absolute value of each human individual. Perhaps it is beyond our strength to love an enemy; but we can look on an enemy through the prism of Divine love. It is entirely within our power to convince ourselves that Christ died on the Cross for him also. Consequently, he, our enemy, is worthy of this! There is something in him worthy of Christ's death. He is not a blank, but God's creature, bearing His image and likeness. God became man so that man might become a god, that is, god-like. God-manhood is the basis of religious life and the basis of the life of the whole world - in as much as man is a microcosm. God Himself is humane; that is why man too must be humane. In men's humaneness, their divine likeness is manifested.

The parable of the Good Samaritan teaches us that any human individual, any man - be he sick, poor, a thief, an enemy - is higher in value than an abstract idea of good, an abstract idea of the common, public welfare, an abstract idea of churchliness, generally accepted traditions, regulations and canons.

The parable of the Good Samaritan teaches us a hierarchy of values: man comes first, and the Sabbath second. Public, social and ecclesiastical institutions exist for man, and not the other way round. We, like the Samaritan, must first of all see the man, his status in society notwithstanding, his splendid clothes or pauper's rags notwithstanding.

The Lord gave us the parable of the Good Samaritan in answer to the lawyer's question about what he should do in order to receive eternal life. When Christ answered with the commandment on love, the lawyer again turns to Him with a question: "And who is my neighbor?" This was the question of the minimalist, who wanted to know the minimum that needs to be fulfilled in order to enter into Life. By the parable of the Good Samaritan, Christ shows both the lawyer and us that the question is not correctly put forth. The parable of the Good Samaritan goes further than a teaching on whom to consider our neighbor. It shows us how to become a neighbor ourselves for each man in need of mercy.

The Patristic interpretation of the parable is highly instructive. According to the thought of the Fathers, the man going down from Jerusalem to Jericho is Adam, who in this case represents all mankind. Our primogenitors, who did not stand firm in good and fell into sin, were banished from Paradise, from the "Heavenly Jerusalem", and had to live in the world, where they were forced to contend with various difficulties. The thieves are a symbol of the demonic powers who envied the purity of the first people and pushed them onto the path of sin, depriving our primogenitors of faithfulness to God's will and of life in Paradise.

The wounds are the consequences of sin, which make us spiritually weak. The priest and the Levite represent the law of the Old Testament, given by Moses, and the priesthood of Aaron, which by themselves could not save man.

The Good Samaritan is Jesus Christ, Who gave us the New Testament and the grace of God (the oil and wine in the parable) for the healing of our infirmities. The inn is the Church of God, where we find everything necessary for our recovery. The innkeeper is an image of the Church's pastors and teachers, whom God charged to care for the flock.

The departure of the Samaritan in the morning symbolizes the appearance of Christ after his Resurrection and also His glorious Ascension. The two denarii, given to the innkeeper, are the Divine Revelation, given in Sacred Scripture and Tradition. Finally, the Samaritan's promise to return to the inn for a final reckoning is a prophesy of the Second Coming of the Lord Jesus Christ, when to each man will be given according to his works.

Here then is a small portion of the rich content of the parable of the Good Samaritan, which teaches us who our neighbor is and how to become neighbors ourselves for others. Beloved, let us love one another: for love is of God; and every one that loveth is born of God, and knoweth God (I John 4:7).