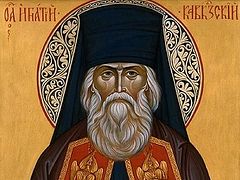

As we commemorate the great saint and spiritual writer St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov), whose volumes address every aspect of Christian ascetical life in our latter days, we are compelled to recall that St. Ignatius gained his profound wisdom through a life of sorrows. Although he was born to a noble family and enjoyed the respect of the Russian emperor himself, St. Ignatius’s deep spiritual sensibility made his life as the superior of the St. Sergius Monastery near the capital city during a period of growing coldness to religious life exceedingly burdensome. Ironically, this man of such profound intellect was often gravely misunderstood by the “scholarly monks” of his day.

After serving as bishop of the Caucasus, St. Ignatius was granted his request to retire to the St. Nicholas Babayev Monastery by the Volga River. We have translated a few excerpts from St. Ignatius’s letters in which he candidly discusses the deep longing of his soul.

I am fifty-seven years old. Seemingly not so old, but I am already coming to the end of my life, because evil have the days of the years of my life been (Gen. 47:9), in the words of the patriarch Jacob. My health is poor by nature; it has been broken by the hardships of life. Greatest of all was this moral hardship: At the beginning [of my monastic life] I could not find a monk who would be a living image of the ascetic teachings of the fathers of the Orthodox Church. My desire to take this direction, because I recognized it as the correct one, placed me in a position of opposition toward everyone and led me into a struggle from which the hand of God, and only the hand of God, led me out to this Babayev [Monastery] solitude. And as you see, they have lifted their voices against an exile, and they do it for this reason: because of their departure from the teachings of the Holy Church and the acceptance of ideas that are at odds with, even in enmity against that teaching...

I am fifty-seven years old. Seemingly not so old, but I am already coming to the end of my life, because evil have the days of the years of my life been (Gen. 47:9), in the words of the patriarch Jacob. My health is poor by nature; it has been broken by the hardships of life. Greatest of all was this moral hardship: At the beginning [of my monastic life] I could not find a monk who would be a living image of the ascetic teachings of the fathers of the Orthodox Church. My desire to take this direction, because I recognized it as the correct one, placed me in a position of opposition toward everyone and led me into a struggle from which the hand of God, and only the hand of God, led me out to this Babayev [Monastery] solitude. And as you see, they have lifted their voices against an exile, and they do it for this reason: because of their departure from the teachings of the Holy Church and the acceptance of ideas that are at odds with, even in enmity against that teaching...

Have no regrets about my departure from social service and do not suppose that I could have brought any benefit. My spirit is decisively foreign to the spirit of the times and I would have been a burden to others. Now they mercifully abide me only because I am far away and in the backwoods...

Not in vain did one holy father say that the sower sows in a row, but he doesn’t know which grain will sprout and which plot of land will produce an abundant harvest.

Precisely so—the path of my life and of those who wish to accompany me is strewn with thorns. But that is the path along which the Lord leads his chosen and beloved! If a man is not led along the path of thorns, he cannot open the eyes of his soul, nor see the spiritual gifts that Christ gives.1

***

I have lived through an era in Sergiev Hermitage during which unbelief and brazen force, calling itself Orthodoxy, crushed our worn out Church hierarchy and mocked and abused everything sacred. The results of these actions can now be felt very strongly. By God’s mercy I desire that everyone forgive everything and think not that anyone is guilty before me, but I do want you to understand the actions of the enemies of the Church and Christ, and recognize them for what they are. After all, the antichrist will call himself “Christ”. And his appearance here should be recognized as justly allowed by God; but the antichrist and his actions have their own price...

We live very quietly, placing our hope in the Lord, Who even during the very time of antichrist will guide His servants and prepare for them places and means for salvation, as was testified in the Book of Revelations.2

***

I am quite happy that my sickliness gives me a weighty excuse for solitude and releases me from that repugnant loquacity coming from justification and accusation, which is so opposed to Christ’s teaching, and torments a soul that, albeit only a little, has tasted the sweetness of a peace that comes from keeping the commandments of our most meek Lord Jesus Christ.

As a sick man, I must have as the haven of my hope not my own works, nor my merits, but the mercy and merits of the God-Man Jesus...

In general my health is very bad. I arrived here half dead. Everything in its own time. There was a time when I gave most of it to my neighbor, and now another time has come—a time when I must direct particularly stern attention to myself, in order to prepare myself through repentance for departure from this life.3

***

In being near the end of my earthly sojourn, I address a greeting of love to all mankind, wishing for everyone all true blessings. I address with special gratitude those few who showed me special love. And amongst this small number—a very small number—are you. I thank your for your sympathy toward me...

I continue to be sick; my illnesses are bound up not so much with intense pain as with exhaustion and fever. Throughout this winter I rarely left my rooms, and from January to now I have not left at all. God’s will be done! Can clay vessels make sense of what is beneficial and needful for them?4

***

God’s special mercy has led me to a calm haven. Whoever desires to serve God must pray to God that He receive this intention and arrange for him an exodus from the world. My exodus has been arranged before your very eyes. Once the convenience has been provided, one shouldn’t fall into duplicity. It is the eleventh hour! The field of repentance can be closed in a brief time by death. There is no time to glance from side to side.

Seeing that my days like a shadow have passed away, and my strength grows extremely weak, moreover long ago having a desire to end my days in solitude, I have submitted my request to the Holy Synod for retirement from my diocesan rule and to be sent to the coenobitic Babayev Monastery in the Kostroma diocese. After doing so I felt a particular tranquility in my soul and even a quiet joy, as if I had fulfilled my duty. It is not my inclination to live in important places and occupy important positions. And now, my weakness and poor health won’t allow for it. If I were to waver in duplicity and put off day after day my good intention to seclude myself for the sake of repentance (from which the enemy of our salvation tries to lure me away under various flattering and specious pretenses), I might spend the rest of my life in that duplicity and indecision and be overtaken by death unprepared. Babaika is a secluded place, has few visitors—especially in winter, when there are no visitors at all—is dry and healthy, by the Volga River. If God grants me this haven, then it can become a haven for many who truly desire salvation, far from the clamorous world.

Ask the hierarch I.’s father to speak about me to the Metropolitan, and if not directly, then through a vicar bishop. This is based on the fact that many scholarly monks have the most perverse concept of me, judging by myself...5

I will tell you about [St. Nicholas-] Babayev Monastery, that it pleases me extremely in all respects. The location is marvelous. What air! What water, what crystal-pure spring water! The springs gush and bubble from the hills in such quantity that I think it would suffice for all Petersburg. What oak groves! With ancient oaks! What meadows! What a Volga! What quietude! What simplicity! I open a book by an ascetical writer, read it, and see that here one can carry out its advice in actual deed—while in Petersburg one can only carry it out in the imagination and desires. In a word, I could not wish for a better refuge for my earthly pilgrimage at this moment.6