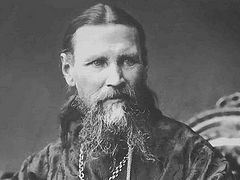

The author of this philosophical contribution is an Orthodox Christian and student of Philosophy and Theology in Oxford, UK.

In the contemporary West we hear a great deal about “social justice”. It is strange that there should be such a preoccupation with justice, given the widespread embrace of secularist and naturalist philosophies in our age, which does not permit the making of any moral judgments beyond our basic preferences. Traditional justice is a question of desert, that is to say, giving the right things to the right people—so it is ultimately a question of what is right. If one thing is for certain, the contemporary West has lost sight of what is right. On the most basic level, many Westerners retain a sense of what is right and wrong—if you were to ask someone whether a murder is right or wrong, you would be hard pressed to find someone of the opinion that “I just don’t like murder.” Almost everyone will declare it to be innately wrong.

Indeed, the secular world has always been faddish, and the latest fad is an inconsistent form of moral relativism and naturalism. It is often said that modern moral philosophy students all prove to be defenders of relativism in their essays until the topic of Hitler is brought up—morality is relative and no action can be judged by a consistent sent of standards, apart from the Holocaust, which, apparently, is the exception to this rule. This example, however, is a perfect staging point for the exploration of a deeper and more important problem: secular faddishness is all very well, fashions come and go all the time, but when it comes to matters of justice, dignity, and desert, swinging from one fad to another can prove incredibly dangerous. David Berlinski in his unique book The Devil’s Delusion, addresses on one such present fad, the fad of scientific atheism, and makes the important point that if one thing is certain, it is that of the greatest mass-murderers of the past century—the Nazis, the Bolsheviks, Khmer Rouge, and so on—there is one thing that holds true for all, that they did not believe God was watching what they were doing.

We are inclined, quite naturally and rightly, to view atrocities as a great evil, and we sympathise with the victims of all disasters and, we hope at least, that we can try to alleviate suffering where we find it. But this “problem of evil” has swollen into a beast that afflicts believers in the modern world in a way that never seemed to trouble the people of previous ages. A good, almighty, and knowing God, we are told, would never allow the world to persist in the state that it is presently in, and as such, God cannot exist, or at least, He cannot be the God of justice and mercy that Christianity claims Him to be. So there is, at least in the minds of many people today, a problem of reconciling a just God with evil and suffering.

As Christians, we worship the Holy Trinity as a communion of love: a unity of three persons bound together intimately not only by existential qualities such as essence and will, but also personal ones such as love, creativity, wisdom, and so on. The creation of the world was not a capricious act performed for the sake of the act of creation itself, but a natural and necessary consequence of the love of the Holy Trinity. Adam’s sin, which brought about the Fall of Mankind, was therefore not merely a legalistic transgression of a cold commandment, but a truly significant event. It was a betrayal of the love of God to which man was closely connected before the Fall, as indicated by the dwelling of Adam and his wife in Paradise. Imagine, if you will, two very close friends, who do everything together and love one another—their relationship is not harmed by minor annoyances and irritating personal quirks, and we know full well that however much our friends’ eccentricities may irk us, if anything they make our friends more endearing to us. But if it comes to light that one of these two close friends has been stealing from the other in secret, or defiling things dear to his friend, or talking ill of him behind his back, then when these sins come to light there is a serious separation, a painful sense of betrayal which damages the relationship, sometimes irreparably. Adam’s sin before God is like this latter sort of betrayal—but how many more times magnified it is to have been committed against God, his Creator!

The sin of Adam has cosmic consequences. Not only does it show humanity the possibility of its further betrayals, but the direct consequence of it is expulsion from Eden, from the Paradise unaffected by suffering, and man’s entrance into the world as it is now. Our presence here on Earth, therefore, is at least in part expiative—the wages of sin is death (Romans 6:23), and it is ultimately sin which gives birth to suffering, the natural consequence of separation from the Good, which is God. Is it any wonder then, that there is so much suffering? As Doctor Samuel Johnson once remarked, “inquiry is not necessary, for whatever is the cause of human corruption, men are evidently and confessedly so corrupt, that all the laws of heaven and earth are insufficient to restrain them.”

Just as in the example of the broken close friendship we saw above, however, relationships can be repaired with time, and with forgiveness. Our God, we know, is most merciful and willing not only to forgive us but to save us from this fallen world; we know this not by guesswork but by His example. One such example is through His Law. Many Christian groups claim that Christianity is entirely free from the Law of the Old Testament, and that it is no longer binding on Christians, given the spiritual rather than worldly nature of the kingdom of Christ. Other groups claim that early Christians kept the Law of Moses, and that modern Christians should too. Neither of these positions are especially helpful, nor is it what the Church teaches. The holy Apostle Paul says that we are not without God’s law, but under Christ’s law (1 Corinthians 9:21), and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself said, Do not think I came to destroy the Law or the Prophets. I did not come to destroy but to fulfil. (Matthew 5:17) So what is this fulfilment of the Law of God in the Law of Christ? How can we be righteous in it?

The Law of Christ certainly involves far more than a platitudinous exhortation to “just be loving”, as certain New Age-like forms of Christianity seen in the modern world might claim. The love of which Jesus spoke is the inner love of the Holy Trinity, a relational love and a supportive love. Saint Paul says, Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfil the Law of Christ (Galatians 6:2), and this is a command, a law, given to the Church. The Law of Moses was a very physical expression of the fact that the wages of sin is death, and it meted out retributive justice in a strict way, and it remains the case that none of the transgressions against God described therein are untrue. But within both written and natural laws there can be injustices, and the ultimate injustice is taken upon Himself by Jesus Christ. The Death of the Lord on the Holy Cross represents not only a tremendous amount of suffering, but one of the worst crimes of humanity, examples of which remain repulsive to us today—the horrific punishment of an innocent and righteous man—the Son of God; in fact, deicide. The Resurrection of the Lord translates this horrifying reality into salvation, and when the Apostles were told of it, even many of them did not believe until they saw for themselves. God reveals the answer to suffering through a mystery: a mystery which shows us that it is the endurance of the worst of this world which is a saving reality. Christ fulfils the Law of Moses through suffering and punishment; so to fulfil the new Law of Christ, the onus is upon us living in the Church after Pentecost.

The Scriptures tell us that Christ is all and in all. We know this to be true, because all things are well-ordered and maintained, there is a Reason, a Logos, in this Universe which sustains all things and makes them beautiful, and we know this to be Jesus Christ through whom all things were made (Creed; John 1:3). But we sons and daughters of Adam have a unique position as free beings with an acute awareness of our own freedom. It is through our actions, therefore, and by knowing that God is watching, that we participate in the Law of Christ. If we want to find the answer to the problem of evil and suffering, and if we want to be righteous before Christ, we must first learn to write the Law of Christ upon our hearts. That begins with repentance, and offering to God our prayers, accepting the miraculous gift of the sacrifice of Christ and resolving to keep His commandments. Beyond this, there is bearing one another’s burdens, which are the result of our sins and the sins of the whole world. We will not reach the end of the road without any sin, nor will reach it by turning towards our sin and embracing it simply because it will not leave us; however, we can reach the end of life bearing each other’s sins in repentance, and bearing the Law of Christ, which calls us to relate to our neighbours. By doing this, by forgiving others, and teaching others to endure, and helping one another along the path to salvation, we perform a work of what the fathers of the Church call synergeia, a synergy or co-operation with God, who is Trinity, who is relationship. It is through us in our struggles against the sinful nature of the world that God works in His alleviation of suffering through His mercy, and we must recognise this as temples of the Holy Spirit (1 Corinthians 6:9). This is what it means to be righteous before God: to keep the Law which allows Him to help His poor creation.

It is to this Law that the Prophets kept, which allowed them to co-operate with God and express their revelations; it is to this Law that Christ compels us to run; and it is to this Law that we will be held to account on that Dreadful Day of Judgment. So let us not be like the world, which has become used to being comfortable and has the arrogance to expect the Divine to remove evil and sufferings from it. Instead, let us give thanks to God always, even for our sufferings, and let us strive to write the Law of Christ upon our hearts, through sympathy with those who sin (of which we are all also guilty), and for the sake of driving out the things which displease God from our souls through mutual prayer and mutual love.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, help us with this!