This article is dedicated to two female saints of Ireland, whose wide veneration from ancient times has continued in the Emerald Isle. Both of them are venerated by modern Orthodox Christians today, and both are depicted on the icon of the Synaxis of All the Saints of Britain and Ireland that can be found in the Russian Dormition Patriarchal Cathedral in London and elsewhere. Their names are Attracta of Killaraght and Monenna of Killeavy.

Three stained glass windows of St. Attracta: A reproduction of St. Attracta's stained glass by Richard King; stained glass inside St. Patrick's RC Church in Gurteen, Sligo, stained glass at the RC church in Killaraght, Sligo (all three kindly provided by Fr. Joseph from the Gurteen parish, Sligo)

Three stained glass windows of St. Attracta: A reproduction of St. Attracta's stained glass by Richard King; stained glass inside St. Patrick's RC Church in Gurteen, Sligo, stained glass at the RC church in Killaraght, Sligo (all three kindly provided by Fr. Joseph from the Gurteen parish, Sligo)

Venerable Attracta, Abbess of Killaraght

Commemorated August 11/24

Only ancient popular oral traditions associated with this saint are credible. All later accounts of her Life, such as that by the Cistercian Monk Laurentius of Boyle in the twelfth century, are controversial and not reliable. Among the authors who wrote of St. Attracta at length was John Colgan, a seventeenth-century Franciscan monk and historian who wrote the fundamental work, Acta Sanctorum Hiberniae (The Acts of the Irish Saints). Holy Mother Attracta (Araght, Atty) is a greatly venerated Irish anchoress and foundress of monastic communities. She was born in the fifth century to a noble family and was a contemporary of St. Patrick, the enlightener of the Irish land, who according to tradition tonsured her.

The future saint was born in what is now County Sligo in the west of the Republic of Ireland, in the province of Connacht. From childhood she dreamed of dedicating her life to the service of God. She prayed fervently, bestowed alms on the poor and fasted continuously for the mortification of her flesh. On learning that her parents did not approve of her decision to lead the monastic life and wanted her to marry (the girl was beautiful and had several suitors), the young Attracta left her parents’ home, taking two companions with her. First the saint moved to south Connacht. Then she lived as an anchoress in Killaraght in south-east Sligo, on Lough (Lake) Gara, and later—at Drum (subsequently renamed Drumconnel because her brother, Bishop Conel, also worked there) not far from Boyle in what is now County Roscommon. The holy woman founded communities for nuns in these places, which grew into famous convents; although according to tradition, the convent at Killaraght was purposely built by St. Patrick who made her abbess there. (It was written that when St. Patrick tonsured Attracta a veil fell on his breast from heaven. Patrick gave it to Attracta and told her to wear it as a special blessing of God till her death. Feeling unworthy of this, she reluctantly agreed only after much persuasion).

The venerable mother also established a number of churches and monastic communities on the territory of the modern Irish counties of Sligo and Galway (on the west coast in the province of Connacht). St. Attracta may also have served as abbess of the convents she had founded there. Notably, the ascetic chose crossroads (“where seven roads met”) as the places to build her convents, because many wayfarers and strangers would pass by them. In all her convents special attention was devoted to care for the sick, and hospitality was extended to everybody. There is ample evidence that numerous healing miracles were performed in these monastic settlements through St. Attracta’s prayers. There were many accounts of cases of healing of paralytics, and in one case the holy abbess raised a drowned man from the dead by her fervent prayer. According to another popular story, St. Attracta by the sign of the cross and a touch of her staff destroyed a “monstrous beast” that used to steal the livestock of rural residents of the Lugna district and terrorize the population.

St. Attracta's Church in Killaraght, Sligo

St. Attracta's Church in Killaraght, Sligo

At Killaraght, St. Attracta opened a hostel (it combined the functions of a “house of hospitality” and a hospital) for travelers that became very famous. This hostel existed till 1539. Though there is no solid evidence, but we can presume that Attracta ruled Killaraght Convent, her main establishment, to the end of her life. People from the village and from all over the region loved and admired the holy woman for her holiness and prudence, both in her lifetime and after her repose, and sought her advice. The Irish revered the saint and had a great affection for her because of her steadfastness and beauty of character. All were charmed by her gracious behavior, her affable and gentle nature. For the destitute she was a most tender and compassionate mother and friend who was always willing to soothe their suffering, listen to their sorrows and guide them to the path of eternal bliss.

St. Attracta reposed in the late fifth or in the sixth century. She entrusted her disciples and successors to practice the virtue of hospitality permanently so that they could obtain favors from our Lord and Master at the Last Judgment. Her convent in Killaraght may have existed until the Reformation. At least it is known that a new church was built on this site after her death and dedicated to Christ, the Mother of God, and St. Attracta, and that this place was considered very holy and a center of hospitality for many years. In the fifteenth century, about 1000 years after the saint’s death, two great relics were venerated at the church of Killaraght: a cross (associated with a miracle of St. Patrick), and the cup of St. Attracta. This church belonged to the Diocese of Achonry, which St. Attracta had taken under her heavenly patronage (its co-patron is St. Nathy).

St. Attracta's well in Clogher, Sligo. Photo: buildingsofireland.ie Now the village of Killaraght in Sligo near the border with Roscommon has a Catholic church dedicated to St. Attracta that dates to 1875 (it belongs to the parish of Gurteen), and the supposed site of her convent is occupied by a cemetery. The parish celebrates the mass in the cemetery every year on the Sunday closest to August 12 in honor of St. Attracta. The parish church has a stained glass window depicting this saint. There is the ancient yet overgrown and half-abandoned holy well dedicated to St. Attracta near the cemetery, in a field by a roadside, although the wells described below are considered far more popular in our days. The neighboring Gurteen has a Roman Catholic Church dedicated to St. Patrick, which has a 1868 stained glass window of St. Attracta (next to that of St. Patrick) in the side altar. The name of this saint can be found in many early Irish martyrologies and calendars.

St. Attracta's well in Clogher, Sligo. Photo: buildingsofireland.ie Now the village of Killaraght in Sligo near the border with Roscommon has a Catholic church dedicated to St. Attracta that dates to 1875 (it belongs to the parish of Gurteen), and the supposed site of her convent is occupied by a cemetery. The parish celebrates the mass in the cemetery every year on the Sunday closest to August 12 in honor of St. Attracta. The parish church has a stained glass window depicting this saint. There is the ancient yet overgrown and half-abandoned holy well dedicated to St. Attracta near the cemetery, in a field by a roadside, although the wells described below are considered far more popular in our days. The neighboring Gurteen has a Roman Catholic Church dedicated to St. Patrick, which has a 1868 stained glass window of St. Attracta (next to that of St. Patrick) in the side altar. The name of this saint can be found in many early Irish martyrologies and calendars.

Veneration for St. Attracta across the Emerald Isle was so great that a large number of places were named after her: Killaraght (“Attracta’s church”), Toberaraght (“Attracta’s well”), Cloghan Araght (“stone structure of Attracta”), and so on. Now the Catholic church at Breedogue in the parish of Ballinameen (County Roscommon), a high school, and a host of holy wells in western Ireland bear the name of St. Attracta. One of these holy wells is situated in Clogher near Monasteraden in Sligo (with Killaraght being on the other side of Lough Gara); its water cures rickets and warts. According to legend, St. Attracta expelled a “serpent” which lived near this well, so the stones lying beside it were called the “serpent’s eggs”. Since the venerable woman made this place holy, in the Middle Ages any woman who wanted to have children could take one of these stones home and return it after giving birth. Some of these “cure stones” still survive next to the well. Its well-house has a number of ancient cross slabs built into it, one of which depicts the Crucifixion scene. This holy spot is visited by modern pilgrims. Another well sits in the settlement of Tample, two miles away from the town of Charlestown in county Mayo (the north-west of the Irish Republic, in the province of Connacht). This well has been considered holy for over 1000 years—Catholics still make pilgrimages here annually on her feast-day (August 11 according to the old calendar) to celebrate the mass and in 1954 a shrine containing St. Attracta’s statue was erected nearby. The church of Charlestown has an image of St. Attracta on one of its stained glass windows.

One more well, in Kiltura, County Sligo, is described by the author Elizabeth Rees in her book, An Essential Guide to Celtic Sites and Their Saints (Burns and Oates, A Continuum Imprint, London—New York, 2003, p. 39): “Kiltura is five miles south of Bunnanaddan... The site… consists of a holy well, a cross-inscribed stone, a memorial slab and a holed stone. These are all within a ring barrow, situated above the west bank of the stream. The eastern side of the barrow falls away into the water. The holy well and stones are on the south-east side of the barrow. The barrow has a raised central platform, and an earthen bank is visible... Attracta's holy well is a tiny artificial inlet leading from the stream. Attracta’s feast was celebrated here until recently, with pilgrims visiting her well and the hawthorn trees that encircled the barrow. Above the well is a sandstone pillar 55 cm high, decorated with a plain ringed cross. Nearby is a slab of purple sandstone with a hole through it. This may have acted as an agreement stone where contracts or pledges of loyalty were made by joining hands through the hole and swearing on it. Such stones are also known as Marriage Stones, where couples would promise fidelity while clasping hands through the stone.”

From the early seventeenth century on, Irish Catholics had the practice of performing “patterns” (from the Gaelic word “pátrún”, most probably meaning “a patron”) in honor of the patron-saint of one or another parish or feasts associated with the Mother of God. After the Reformation, all of the Irish monasteries were closed and many shrines destroyed. And after the Penal Laws had been imposed almost all Catholic buildings in the country were confiscated and Catholic worship virtually banned, so faithful Catholics had no other alternative than gathering in rural areas on special days to pray by the holy wells, monastic ruins or the saints’ graves in the open. These “patterns”—that is, devotional prayer practices, attracted hundreds of pious Catholics from large areas. Thus the local saints were not forgotten, and they combined the Catholic mass, prayers, and penitential practices with some Irish folk traditions. According to various reports, a lot of healings took place in these places. Holy wells (and St. Attracta’s wells were no exception) were the main focus of their veneration (it was not until the nineteenth-century that chapels were built next to most of the wells).

Frequently these holy places were visited by individual believers during the year, and even Protestants joined the gatherings. However, since these meetings were also intended for socializing, there were numerous excesses, such as drinking, fighting, horse racing, dancing, flute playing and immorality, right beside the holy wells. So the Catholic Church had to take measures, and from the 1850s on edicts were issued to forbid these festivals (even after the Emmancipation when the Church was free!), but people did not obey, and the “patterns” only slightly declined. The general revival of the “patterns” began from 1900, though now it was limited to Catholic priests with their parishioners visiting holy wells, ruins or chapels near the patronal feasts to say the mass or hold a prayer service. “Patterns” in a number of holy places of Ireland (notably in Ardmore, the great shrine of St. Declan) still survive among Catholics today.

In his book, A Hidden Church, The Diocese of Achonry 1689–1818 (publisher: Columba, pp. 275–276), Fr. Liam Swords writes that eight parishes had wells dedicated to St. Attracta. Her feast-day was August 11, when patterns were held in Gurteen (Killaraght), Charlestown (Kilbeagh) and Kilcolman (four miles from Ballaghaderreen), and also in Bunninadden (Kiltura), Achonry, Attymass, Killasser and Tourlestrane (Kilmactigue, where people were healed from epilepsy). There were two patterns in one week in the area around Gurteen. St. Attracta’s at Killaraght was followed a few days later on August 15 at Toharna Naomh in Kilfree. Many of the wells still have altar-like structures—an indication that priests used to say the mass by them.

St. Attracta's Church in Tourlestrane, Sligo. Photo: kilmacteige.com

St. Attracta's Church in Tourlestrane, Sligo. Photo: kilmacteige.com

County Dublin, where the capital of the Irish Republic is situated, has an “oratory” (in fact a church) in honor of St. Attracta in Meadowbrook, along with a street and a junior school that are named after her. People and parishioners in the village of Tourlestranein County Sligo pray to St. Attracta as to their heavenly patroness; the local church is dedicated to her, as is the holy well in Glenavoo nearby, to which substantial pilgrimages are organized close to her feast day. Among other places, St. Attracta is depicted on a stained glass window in the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Ballymote in county Sligo. This Catholic church was built in the nineteenth century to the design of the British ecclesiastical architect George Goldie (1828–1887).

In 1864, under Pope Pius IX (1846–1878), the veneration of St. Attracta among Irish Catholics was officially promulgated all over Ireland.

In art, St. Attracta is often depicted with a deer. This tradition is connected with the following miraculous story. Once through the holy maiden’s prayers, during the construction of a castle for one local Irish ruler, some wild deer were substituted for the exhausted horses and helped the builders transport the felled trees from the forest.

There is a well-known St. Attracta’s stained glass image created by the stained glass artist from Mayo, Richard King (1907–1974), who loved the local saints, depicted many of them in glass, and even died on St. Patrick’s day. Many of his paintings can be found in the Capuchin Annual—one of the most read Irish publications, published in Dublin by the Irish Franciscans between 1930 and 1977.

Over the centuries, many Irish girls, especially in the western part of the country, were baptized with the name “Attracta” in honor of the early Orthodox Saint, who was noted for her hospitality, charity for the needy, homeless and travelers, and the gift of healing. Many women who are aged over forty have Attracta as their baptismal name even today, though very few in recent years.

Venerable Monenna, Abbess of Killeavy

Commemorated: July 6/19

St. Monenna's grave at Killeavy, Armagh

St. Monenna's grave at Killeavy, Armagh

For many centuries Irish people have loved and venerated St. Monenna (Moninne, Darerca, Bline; c. 432–c. 517 or 518).She was born in the present-day County Down in Northern Ireland. Her father, Machta, was a local ruler, and her mother, Comwi, was the daughter of a northern king. The holy maiden founded and became the first abbess of Killeavy Convent in what is now County Armagh in Northern Ireland.

Initially, only eight maiden nuns and a widow were her companions, but by the end of her life she had gathered around 150 disciples. Imitating the Desert Fathers, the anchoresses led an amazingly austere ascetic life, living in extreme poverty and at a bare subsistence level. The hermitesses chose the Prophet Elias and St. John the Baptist as their heavenly patrons. St. Monenna performed most of her spiritual labors for Christ’s sake on Slieve Gullion—a mountain in the south of County Armagh 573 meters (1,880 feet) high, and that is why she is sometimes nicknamed, “Prophet Elias’s spiritual daughter”.

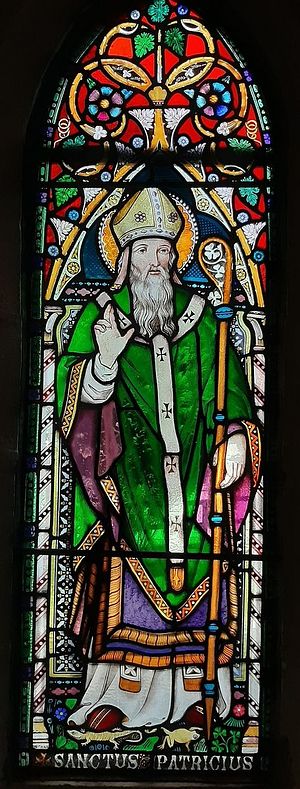

St. Patrick's stained glass window at St. Patrick's RC Church in Gurteen, Sligo (kindly provided by Fr. Joseph from the Gurteen parish, Sligo) According to tradition, the venerable woman personally knew such great saints of the Irish Church as Sts. Patrick of Armagh and Brigid of Kildare. St. Patrick may have baptized St. Monenna when she was an infant, and she may have lived with St. Brigid at her celebrated Kildare Monastery for some time. Tradition holds that St. Patrick predicted to Monenna’s parents that their daughter’s nationwide veneration would continue to the end of time. Later, the apostle of Ireland tonsured the young Monenna a nun. A relative of St. Monenna was St. Ibar (feast: April 23) who is venerated as one of the first bishops and evangelizers of the Emerald Isle. She and her community may have stayed at a monastic site near Begerin in County Wexford briefly and were trained by St. Ibar.

St. Patrick's stained glass window at St. Patrick's RC Church in Gurteen, Sligo (kindly provided by Fr. Joseph from the Gurteen parish, Sligo) According to tradition, the venerable woman personally knew such great saints of the Irish Church as Sts. Patrick of Armagh and Brigid of Kildare. St. Patrick may have baptized St. Monenna when she was an infant, and she may have lived with St. Brigid at her celebrated Kildare Monastery for some time. Tradition holds that St. Patrick predicted to Monenna’s parents that their daughter’s nationwide veneration would continue to the end of time. Later, the apostle of Ireland tonsured the young Monenna a nun. A relative of St. Monenna was St. Ibar (feast: April 23) who is venerated as one of the first bishops and evangelizers of the Emerald Isle. She and her community may have stayed at a monastic site near Begerin in County Wexford briefly and were trained by St. Ibar.

Later in life, the holy mother founded the convent at Killeavy (“church of the mountain”) under the shadow of Slieve Gullion and ruled it for many years. Abbess Monenna was renowned for her generosity and particular mercy; she cared for the poor, and illnesses were cured by her prayers—once she healed a mute man. According to tradition, at her convent St. Monenna brought up and educated Luger—the son of the above-mentioned widow and nun who lived with her. Subsequently he became a bishop.

At first the area around her convent was inhabited by pagans who practiced cruel customs. Little by little, seeing the good example of the life of St. Monenna’s community, many embraced the faith of Christ and flocked to the anchorites for consolation and intercession. It was related that towards the end of Monenna’s life she was visited by angels. Once a wealthy man brought new clothing to Killeavy Convent as a gift to the community because the old habits of the abbess and her nuns were tattered and worn. But Monenna refused to accept this gift, saying that the Almighty provided them with all they needed. She sold the clothing and distributed the money to the poor.

Stories relating to the astounding ascetic life of Monenna abound. It was rumored that some other saints would visit Monenna to keep her in check because sometimes she introduced an extremely austere program of fasting at her community that brought her and her closest disciples to the brink of death from starvation. It is known that for centuries, Killeavy Convent kept a very special relic: the personal comb of Monenna, called “St. Darerca’s comb”, with which the saint would comb her hair once a year—on Holy Thursday. Her hoe and badgerskin dress were also preserved as relics. At night time the holy maiden always managed to read the whole Psalter, standing in the cold waters of a spring.

Killeavy was not the only achievement of Monnena in Ireland. She certainly founded other convents in the Irish land, notably in Faughart, in the east of what is now the Irish Republic in County Louth, which was formerly part of the province of Leinster. In addition, the foundation of churches or monastic communities in Scotland is attributed to St. Monenna, though this is unlikely to be true. At the very least, some nuns who were trained at Killeavy Convent were indeed sent to Scotland to found new monastic communities there. Interestingly, according to one version, young St. Monenna and her companions were instructed at St. Ninian’s Monastery in Whithorn in Scotland.

After the holy abbess Monenna had reposed at a very advanced age, her grave at Killeavy Monastery became a focus of veneration and a popular pilgrimage destination. In the Middle Ages it was one of the most important female monastic sites in Ireland. Killeavy is situated at the foot of the eastern slopes of Slieve Gullion within a very idyllic area with exceptionally beautiful countryside and countless historic artefacts. Monenna is still widely venerated in Ireland, as she was throughout the centuries, especially in its northern regions.

There is an account of a posthumous miracle of St. Monenna. The fourth abbess of Killeavy, during the construction of a wooden church, found that it was impossible to carry a long timber down from the mountain to make the roof ridge. She prayed fervently to St. Monenna, and on the following day the sisters saw the same timber lying right beside their convent! Later, in the post-Norman convent, that very timber was kept as a relic.

Killeavy Old Church ruins, Armagh

Killeavy Old Church ruins, Armagh

In Killeavy—the site of St. Monenna’s main convent—various ruins and her supposed grave, marked with a huge granite stone on the north side of the cemetery, still exist. After St. Monenna’s death her convent was under the care of the Culdee movement, which strove to retain old ascetic practices in the Irish Church. The first church on this site was wooden, and it was rebuilt with stone in the sixth century. This monastic settlement was plundered by the pagan Scandinavians in 923, but nevertheless monastic life in Killeavy was resumed, and Augustinian nuns used the site from the twelfth century till 1542, when it was closed during the Dissolution under Henry VIII. Now the walls and other remains of two ancient churches (the smaller and the larger ones) are distinguishable, judging by which we can say that the buildings were grand and impressive. One of the churches was pre-Norman, which makes it the oldest surviving church structure in County Armagh. Among the surviving structure are a large granite doorway, an arched window and carved angels. As St. Patrick prophesied, the memory of St. Monenna and love for her still live on in Ireland, 1,500 years after her death.

St. Monenna's holy well near Killeavy, Armagh. Photo: megalithicireland.com St. Monenna’s holy well on the slopes of Slieve Gullion not far from her former convent survives to this day.

St. Monenna's holy well near Killeavy, Armagh. Photo: megalithicireland.com St. Monenna’s holy well on the slopes of Slieve Gullion not far from her former convent survives to this day.

Every year numerous pilgrims visit St. Monenna’s grave at Killeavy and her holy well on her feast day. The water of her well (situated c. 450 meters or 1476 feet to the southwest of the cemetery on a mountainside and accessible by a narrow muddy path) heals eye diseases and other ailments. In the twentieth century the well was covered with a shrine with the statue of the Mother of God.

Remarkably, at least four early saints with the name “Darerca” are venerated in the Irish Church.

In the ninth century, St. Oengus of Clonenagh (feast: March 11), the celebrated author of the calendar of saints and the hymn to the Irish saints called Felire, praised St. Monenna (among other saints), calling her “a beautiful pillar” who “gained a triumph and hostage to purity”, becoming “a kinswoman of the great Virgin Mary”.

Holy Mothers Attracta and Monenna, pray to God for us!