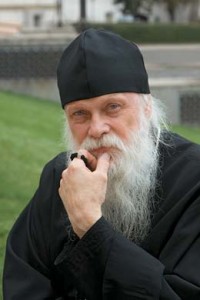

In our conversation, Father Gabriel told us about the motives for his decision, about the main differences between Valaam and Switzerland, and about many other things.

“We Are Like Weirdos”

Q: If someone comes from one Christian tradition to another, it must mean that they feel they lack something vital in their spiritual life…

A: Yes. And if this person is seventy years old, like me, this step cannot be called a hasty one, can it?

Q: No, it can’t. But what did you lack, being a monk with such a great spiritual experience?

A: I have to speak not of one decision, but of the whole life journey with its inner logic: at one point an event happens which was being prepared by one’s whole life.

Like all young people, I was searching for my way in life, so to speak. I entered the University in Bonn and started studying philosophy and comparative theology. Not long before that, I had visited Greece and spent two months on the island of Lesbos. It was there that I saw a real Orthodox monastic elder for the first time. At that time, I was already inwardly being drawn to monasticism and had read some Orthodox literature, including Russian sources. That elder amazed me. He became the incarnation of the monastic that I had come across only in books before. Suddenly, in front of me, I saw a monastic life which from the very beginning seemed to be authentic, true, the closest to the first Christian monks’ practice. Afterwords, I was in touch with that elder my whole life. So I got an ideal of monastic life.

When I came back to Germany, I joined the Order of Saint Benedict – it seemed to be the closest to my aspirations. The structure of the Order itself resembles one of the early Christian Church. In the Order, there is no vertical system of subordination, each community exists on its own. What guarantees the unity of these communities is the tradition and the Church Typicon. That is, not the juridical order but the spiritual ideal. By the way, in this sense I think that it is the Benedictines, of all Western believers, who are ready to understand the Orthodox believers most keenly. But still my spiritual Father and I saw very soon that with my fancy for Eastern monasticism and the love of Eastern Christianity on the whole, I was not in my proper place in this Order. So the abbot, an elderly and experienced man I still honor, decided to transfer me to a small monastery in Belgium, and not without regret. I spent 18 years there, acquired great experience, and from there, with a blessing, I went to the skete in Switzerland. All those transfers were caused by one reason: the attempt to progress to authentic monastic life, as it was with early Christians. Like the one I saw with Eastern Christians.The most recent step on this way was the conversion to Orthodoxy.

Q: Why did you decide to adopt it? One can love Orthodoxy with all one’s heart and stay within the traditional Catholicism. There are many such examples in the West.

A: Yes, many people who are drawn to Orthodoxy stay within the Catholic Church. And this is normal. In the majority of Western cathedrals there are Orthodox icons. In Italy, there are professional schools of icon painting taught by Russian specialists and others. More and more believers in Europe are interested today in Byzantine hymns. Even the traditionalists of the Catholic Church have been discovering Byzantine singing. Of course they do not use them during the divine service in the church, but outside of the church, for example, at concerts. Orthodox literature gets translated into all European languages, and the books are published in the major Catholic publishing houses. In short, in the West they really have not lost the taste for all authentic, Christian, that the Eastern tradition has preserved. But, alas, it changes nothing in real life of people and society on the whole. The interest in Orthodoxy is more cultural. And those wretched people like me who have a spiritual interest in Orthodoxy, are left in the minority. We are like weirdos; we are seldom understood.

“Simply to Know Where Everything Comes From”

Q: As a theologian, you have often spoken on the problem of West and East’s separation. Can we say that your conversion to Orthodoxy is the result of your meditation on this topic?

A: When I was in Greece and started turning towards Eastern Christianity, I began to perceive the schism between the East and the West very painfully. It stopped being an abstract theory or a plot in a Church history book, but rather something that was directly affecting my spiritual life. This is why the conversion to Orthodoxy started looking like a very logical step. In youth, I sincerely hoped that the union of the Western and the Eastern Christianity was possible. I was waiting for it to happen with all my heart. And I had some reasons to believe in it. At the Second Vatican Council, there were observers from the Russian Orthodox Church, including the current Metropolitan of Saint Petersburg and Ladoga Vladimir (Kotlyarov). At that time Metropolitan Nikodim (Rotov) was very active in international affairs. And many people thought that the two Churches were moving towards each other and would eventually meet at one point. It was my dream that was becoming more and more real. But as I was growing older and learning some things deeper, I stopped believing in the possibility of the reconciliation of two Churches in terms of the divine services and institutional unity. What was I to do? I could only go on searching for this unity on my own, individually, restoring it in one separate soul, mine. I could not do more. I just followed my conscience, and came to Orthodoxy.

Q: Isn’t it too radical an opinion?

A: While still in Greece, being a Catholic, I realized that it was the West that separated from the East, not vice versa. At that moment, it was unthinkable for me. I needed time to understand and accept this. I cannot blame anyone, of course I can’t! We are talking about a whole big historic process, and we cannot say that this or that person is to blame for this. But facts remain facts: what we call Western Christianity today was born as a chain of ruptures with the East. These ruptures were the Gregorian reform, followed by the separation of the churches in the XI century, then the Reformation in the XV century, and finally the Second Vatican Council in the XX century. This is, surely, a very rough scheme, but I think it is correct on the whole.

Q: However, there is an opinion that the chain of these ruptures is a normal historic process because any phenomenon (and Christian Church is no exception) goes through its stages of development. What’s the tragedy in that?

A: The tragedy is in the people. In a situation of radical, revolutionary events there always appear people who start to divide life into ‘before’ and ‘after.’ They want to start counting only from this new point as if everything that happened before had no meaning. When the future Protestants proclaimed the Reformation, I do not think they knew it would lead to the separation of the Western Church into two big camps. They did not realize it, they just acted. And they began to divide those around them into the healthy ones – those who accepted the Reformation – and the unhealthy, sick ones – the followers of Pope.

Moreover, history repeats itself: the same is happening now around the Second Vatican Council within the Roman Catholic Church. There are people who did not accept its decisions and people who consider it to be some kind of a starting point. And everybody reasons along those lines. A simple example: if in a conversation, someone mentions ‘council’ without any additional details, everybody automatically assumes that they are talking about the Second Vatican Council.

Q: What’s your opinion on the modern liberal moods among Catholics?

A: I am very glad to have the opportunity to address myself to the Russian audience and say that you should not reduce all Catholics to one level. Among them are such who would like to be more secular, more liberal. It does not mean they are criminals, it’s just their point of view on life. There are others, those who are fully dedicated to tradition. I would not call them traditionalists, because tradition itself is not so important to them. This is not an ancient folklore that one must nourish artificially and keep aswim. No! Tradition to them is what in every epoch ensured and still ensures live personal contact with Christ, everyday living in God’s hands. As John the Theologian said, “That which we have seen and heard we declare to you, that you also may have fellowship with us; and truly our fellowship is with the Father, and with his Son Jesus Christ” (1 John 1:3). I am sure that the position “there is God and there is me” is for heretics. For Christians, it is “God, me and everyone else.” Everyone else is other believers, and those who for many centuries have preserved the faith for us. If people had not listened to other people so devotedly, if they had not written it down and had not passed it on, there would have been no New Testament. It means there would have been nothing…

Q: And what, in this case, should our attitude be to those who are not very dedicated to tradition?

A: We should not beat them in the face and of course we should not chase them out of the Church. Any person deserves Christian mercy. If I, being an Orthodox, saw a Catholic in an Orthodox church, I would like to approach him and tell him openly, softly, and confidentially, “Listen, brother, you might be interested to know that in the beginning we all crossed ourselves in this way: from right to left. Now everything has changed. No, I am not calling you to reconsider all your life and rush to the Orthodox Church. I just want you to know where things came from.”

Valaam

Q: And why did you choose the Russian Orthodox Church?

A: I think the key factor in such decisions is the people who surround you. When my acquaintances, Russian bishops from Saint Petersburg, learned I was adopting Orthodoxy, they said,

“We are not in the least surprised! You’ve always been with us. But now we are going to have closer communion, a sacred one – at one Chalice.”

I’ve known Metropolitan Hilarion, the current head of the Department for external church relations of Moscow Patriarchate, for a long time. We first met in 1994 when he was a hieromonk. I consider him to be my good friend and I cherish this friendship.

Hierarch Hilarion, if you will, is one of the most competent and knowledgeable people I’ve ever met. He actually became for me the only person I could turn to with my request, who knew me, my beliefs and my situation. And who, as I was sure, was ready to respond. And that’s what happened.

Q: How will it help you in reaching your ideal of spiritual life?

A: You want prophecy from me, but I am no prophet. I do not know specifically what will happen next. We shall simply live. Even now I have already found in Russia many things that keep me interested.

For example, I visited Valaam. You know, in the West if a believer is drawn to a life utmost monastic seclusion, he actually has nowhere to go.

Hermitages such as they are in Russia, do not exist in the West. This form of life seems to be outdate already. As a monk I am constantly in search for the utmost seclusion, even loneliness. In Valaam, I felt all of it was there.

Q: Isn’t there enough loneliness in your skeet in Switzerland? Valaam is also a crowded place, pilgrims come there regularly.

A: Switzerland is a small and densely populated country. The skete is surrounded by a forest, but in a 15 minutes walk there is a village with approximately a hundred people living there. In Valaam it is much more quiet. Yes, of course, there are many people there. But the place itself, as I felt, is isolated from the rest of the world. Maybe it is so because it is an island, or maybe it is due to other, non-geographic reasons.

It seems to me that all this can give rise to this desirable state of seclusion in the heart of everyone who comes there.

Q: Is it more difficult in Europe?

A: To put it roughly, we can say this does not exist in the West altogether. The authentic monastic tradition in the West was practically stamped out in the course of the French bourgeois revolution in 1789. I have a firm belief that the consequences of this revolution for Europe were no less heavy than the consequences of the 1917 revolution and the 70 years of atheist power for Russia. In France after those bloody events monasticism had to be restored almost from scratch. Common priests, not monks, were to perform this. There was no one else. In Russia monasticism survived in-spite of all the shocks and horrors. Yes, it happened at the level of particular individuals, namely, elders. But they existed! And they kept the spiritual tradition and authentic monastic life. It seems to me that in everything that concerns monastic life, Russia did not have to start from scratch. This is why I am sorry to hear Russians say sometimes

“we had it all destroyed, the Church was stamped out, etc.”

I always want to respond, “On my opinion, you have it all, new martyrs and confessors, monastic elders.” And they are all near, just stretch out your arm. Only you have to stretch it out, take this wealth and use it in practice, so to speak, in your life. I often get the impression that the majority of people in Russia do not value this. Or they just do not understand that this is valuable.

Q: Why, in your opinion, does it happen so?

A: Speaking of problems, people concentrate on material, at times external difficulties that monasteries and the Church face nowadays. Yes, there is much to reconstruct. But this is only the technical part, so to speak, only the walls and the roofs. It goes without saying, people complain: roofs and walls cost money, and where can one find money… But if we mentally go above the roof – let it be with holes – we shall see that the walls is not the main thing, it’s more important with what kind of heart one enters the walls. The Russian saying goes,

“The church is not in the logs but in the ribs.”

And this is the most important thing, this spiritual tradition, that is still within Russians. Monastic elders and new martyrs preserved all of this for us. Sometimes people argue,

“But there are so few elders now, most of them died already. There is no one to teach us.”

I always respond,

“If you have no living elder to teach you, turn to the deceased one. You have his hagiography, his texts, his teachings. Read them, and correlate with your life.”

I don’t mean to say that I have never met people in Russia who know, value, and cherish this knowledge. There are many, many people who do and my visit to Valaam proved it.

Jump into the Water

Q: What must change now in your daily life after the conversion?

A: Of course, there are things that cannot but change. Having become a member of the Russian Orthodox Church but still living in Switzerland, I submit to Archbishop Innokenty of Korsun. My relations with the Catholic Church cannot, naturally, remain the same.

Q: What reaction do you expect from your spiritual children? They must be all Catholics…

A: Firstly, I fortunately deal with good understanding people, and I am sure they will respect my decision. And secondly, I have never kept my opinions and beliefs in secret. All my spiritual children have known that my ideal of Christianity is in the East. I do not think they will be that surprised. I had not said anything to them beforehand to avoid unnecessary discussions. But I do not think anything extraordinary will happen. I believe that the tradition of spiritual talks my children used to come for will remain, I have no reason to stop it. Finally, people I communicate with regularly share my spiritual ideal more or less; otherwise, they would not be coming.

Q: What about divine services?

A: Of course, from now on I won’t be able to administer communion to Catholics. But even before I used to do it very seldom: the skete is away from the big world, the territory is kept locked, the services are also private, the chapel is small – for ten people at the most. Only at Christmas and Easter we open the doors for everyone who wants to join us.

Q: If you could and wanted to give contemporaries a very short piece of advice about organizing their praying life, what would you say?

A: If you want to learn to swim, jump into the water. Only that way you can learn. Only the one who prays will feel the meaning, the taste and the joy of prayer. You can’t learn to pray sitting in a big warm armchair. If you are ready to kneel, to repent sincerely, to raise your eyes and hands to Heaven, then many things will be revealed to you. Of course you can read many books, listen to lectures, talk to people – these are also important and help to understand more. But what is the value of all these things if we don’t take any real steps afterwards? If we don’t start praying? I think you must understand this, too. Obviously, you are asking this question from the position of one who does not believe…

Q: Exactly. Our magazine is for those who doubt.

A: There is nothing wrong with doubts, they are even useful. One should not search for them, however. But if they do appear, one must simply recall that we all have a chance to hear,

“Reach your finger, and behold My hands; and reach your hand, and put it into my side: and do not be unbelieving, but believing” (John 20: 27).

Translated by Olga Lissenkova

Edited by Yana Samuel and Isaac (Gerald) Herrin