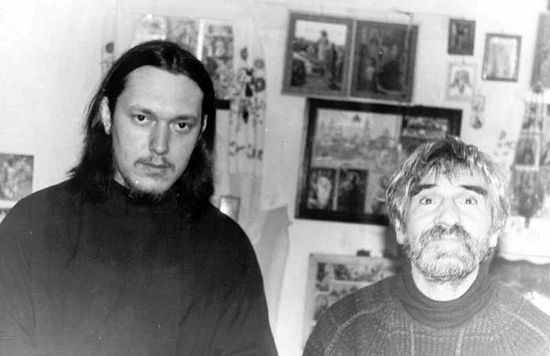

Archimandrite Avvakum (Davidenko).

Archimandrite Avvakum (Davidenko).

* * *

—Fr. Avvakum, the Pochaev Lavra always leaves an indelible impression on all those who visit it. What impressions do you remember?

—It was August 10, 1977. Matushkas Augusta, Magdalena, and psalmist Tatiana from the town of Romen, who served in the cemetery Church with Fr. Alexei, made an ex-prompt agreement to go to the Pochaev Lavra for a pilgrimage and set off… Well, they took me along; I was still a schoolboy, who had only heard about it from people's stories.

The entrance into the main gates of the Lavra are just like entering the Kingdom of God. They made such a great impression on me. Even if I had never been in the cathedrals and churches of the Lavra, my passage through the holy gates alone would have been enough for me.

Over the entrance archway is an image of the Mother of God in a pillar of fire, with Saints Job and Methodius [of Pochaev] standing at either side. The radiance of a light of an either rising or setting sun—it's hard to tell from the icon; you can only see the glow—very effectively inclines you toward a contemplation of the mystery of existence. Peace reigns in the courtyard despite the crowd of pilgrims running to and fro. Conversations are muffled. And above this whole world soars the enormous cupola of the Dormition Cathedral. Its tarnished gold, not yet restored, was nevertheless still impressive, although it was so darkened that you could see the little squares that held it together.

We often want something miraculous, unusual, and it is here in Pochaev, like a live-giving breath of spring poured out everywhere and over all! Here the soul is at rest and flies up to heaven like a bird. The sun shines brightly. The wind brings the smell of field flowers. In the lanes of the Lavra there is a multitude of pigeons. All kinds of pilgrims bustle here and there with netted knapsacks over their shoulders—string-bags that reveal everything they carry; now and then you can see a backpack (they had only just come into use here).

—What do you remember about the fool-for-Christ, Peter? Tell us about him.

Fool-for-Christ Peter of Pochaev.

Fool-for-Christ Peter of Pochaev. I was interested in the outward appearance of this man, his facial expressions, inimitable grimaces, and most of all, Matushka Augusta's assertion about his knowledge. I set myself a goal to study Petro in greater detail, if only visually. True, in time I tried to talk with him.

After I had become a novice in the Lavra, then received the tonsure and priestly rank, after Petro's death, I learned something about his biography. His last name was Gerasimchuk, his name Peter Zakharovich. He was born in the village of Markivtsi, Shepetovsky region. He labored in asceticism in the Lavra itself, attended the services regularly over a long period of time—from sometime in the 1950s up to his death in the mid-1980s. He was never mentioned anywhere in the chancery notes of Pochaev Lavra, but he spent nearly his entire life in its churches.

—How did the brothers relate to him?

—The Pochaev monks for the most part never had any illusions about Peter. Fr. Nicholai (Kovalchuk), the assistant steward in the 1980s, said, "Well, apparently Petro was sick by nature. Sick, and very sick." Fr. Nicholai had the obedience of head bell-ringer and knew Peter very well, because the fool-for-Christ loved the bell tower and would climb up it along with the pilgrims any time it opened. One day, Fr. Nicholai related, Peter began to beat the small bell from joy with a hammer on Pascha, so hard that it cracked and lost its ring. I don't know if it was replaced or if it is still there.

At one time there lived with us in the Lavra one Alexander from the Urals. He was self-important, stocky fellow, who said he was a brick oven builder. There was one incident with this Alexander, a right proud young man. He really did not like the blessed one, Peter. There are certain psychological types or characters who cannot even endure the sight or presence of some they dislike. Once, Alexander saw Petro hanging around him; he took two Brezhnev era rubles out of his wallet and said contemptuously, "Here, take this! And now go away, get out of my sight, and don't hang around here… I don't want to see you around here! Peter took the rubles in silence, but in his soul, judging from his grimace, he was offended. With furrowed brow, he quietly walked up behind Alexander, made the sign of the cross over him twice, straightening out the bills, placed them on both of Alexander's shoulders like military stripes, and left… When the brothers noticed this they started laughing most inappropriately during the most solemn part of the service. Alexander was crossing himself, making bows from the waist, but the rubles stayed on his shoulders as if they were sewn there. The dean of the monastery went and took the ill-fated rubles off his shoulders in order to stop the commotion.

—In what did his podvig consist, other than his humility, patience, and rejection of the world? Was he clairvoyant, as many fools-for-Christ are?

—Before the authorities began to escalate their persecutions, Peter began to be worried. In great anxiety, like a nut, he ran around the Lavra and beat his quilt jacket against the corners, as if putting out a fire. "What is he doing?" the brothers and pilgrims were wondering. But this is how he foretold the coming persecutions.

He never had a cell of his own in the Lavra. He was never numbered among the brethren, but he was one of them. And no one, beginning with the abbot and ending with the newest novices, ever disputed his right. He would spend the night in an empty cell or guestroom. After the police cruelly beat him up, he would sleep in the hay loft next to the horse stables in order to avoid a repeat of that violence. It was relatively warm there, and no one would come to check his passport.

I asked the dean, Fr. Alipy, "How should I relate to Peter, for whom the pilgrims have such reverence? Can he be considered a true fool-for-Christ, like the ones you read about in the Lives of the Saints?" He thought a bit and said, "There are no true or false fools-for-Christ. Each one has his own relationship with God! In this terrible life there is only a living, suffering person before God." This answer was more than instructive for me.

Another example. Matushka Irina told me the following: "They gave me a colorful skirt as a gift. Well, I thought, I will put it on for warmth. I put it on under my black dress and went to Vespers. The fool-for-Christ Peter walked into the Dormition Cathedral and mumbled, "There is monasticism, but worldliness remains. It remains in us!" He walked up to one side, then another, and kindly grimaced. Oy, I looked—my colorful skirt had fallen out from under my black monastic dress and was lying on the floor, spread out like a large, red flower, with red poppies."

—Did the blessed one talk to pilgrims? Did he receive their alms?

—Here is one peaceful scene from those blessed days. The sun is shining. Near the bell tower sit pilgrims on the benches, resting between services; some of them give Peter money and prayer lists. He wrinkles the paper in his hands, rolls it around, and sniffs it. Then he lifts up the list, looks at the light of the sun, and says, "A good piece of paper. Well, remember, Lord, those who have departed, and so that those who remain would keep going!"

Or another incident. In the morning the pilgrims are going to the monastery and see a large snowdrift swept up, and out from under it peeks something black, like a coat. They brushed it off, and it was Petro! He had spent the night in the snowdrift. Almost frozen to death. They brushed him off, led him to the kitchen where it was warm, gave him hot water to drink, and warmed him up. As it turns out, the police had taken him in, questioned him for a long time, beaten him up, and then simply thrown him into the snow outside. He had crawled to the Lavra…

My obedience was in the kitchen. Early in the morning I stoked the brick oven and filled the kettles. I see that Peter is splashing around, washing his hair with cold water running from the spigot. He is completely red, like a lobster.

The pilgrims give him various things to eat, but he doesn't want them. He nods, as if to say, put it in my coat pocket. Zoya, our parishioner, put an orange in his pocket, but it was full of holes. The orange passed through his coat, instantly found itself joyously free, and rolled away from Peter. "Oy, Peter, what's that you have?!" "Ah, see? God doesn't accept it! It's not my fault, not my fault…"

He really loved to listen to the bells, and also loved to ring them. This was his element, his manner of existence, and the activity connected with him. He dreamt of a large bell, ten meters in diameter: "If only such a bell could be forged and rung—for the repentance of the world."

—Did he receive the monastic tonsure after all?"

—Yes, not long before his death he was tonsured a monk and given the name Pavel. After his death, certain others tried to copy him, but with time they understood that it is impossible to emulate him. He was a unique individual, and God gave him the gift to be what he was. Madmen called his life madness, but he is among the righteous and his lot is with the saints. Many of the brothers treated Peter with respect and compassion. Some, I repeat, even tried to emulate him. Thus, Fr. Ignatius, who was in charge of the refectory, went to Fr. Bogdan to get a blessing for foolishness-for-Christ… Fr. Bogdan thought about it, and then said, "We are foolish as it is, and if we act even more foolish, then things will get really bad! I don't bless you—period!" But there were known incidents when fools-for-Christ saved the monks during crisis situations.

There was a young steward in the Lavra, Fr. Dimitry. Not knowing legal fine points, he once bought some boards without the necessary documents. When it was discovered, they called him into the police department, the prosecutor, and wanted to give him a prison term. He went to his spiritual father, who gave him strict orders to temporarily become a fool-for-Christ—to act insane in order to save himself. At the police department they yanked him around a few times, but finally laughed and kicked him out, seeing his "madness." Thus Fr. Dimitry, later the choir director and a schema-archimandrite, a well-known elder of the Lavra, at the blessing of his spiritual father became a fool-for-Christ and saved himself from the Stalinist prisons and camps. The Apostle Paul spoke about this many times: For after that in the wisdom of God the world by wisdom knew not God, it pleased God by the foolishness of preaching to save them that believe (1 Cor. 1:21).

—Batiushka, why do you think fools-for-Christ exist?

The Pochaev Lavra.

The Pochaev Lavra. These people renounced for the sake of Christ not only all goods and comforts of earthly life, but even the generally accepted norms of behavior in society. They walked barefoot in winter and summer, and some even went without clothing entirely. Fools-for-Christ often broke moral codes, if you look at it as the fulfillment of specific ethical norms.

Many fools-for Christ, having the gift of clairvoyance, took on the podvig of foolishness for Christ out of their deeply cultivated humility, so that people would ascribe their clairvoyance not to them, but to God. Therefore they often spoke in hints, allegories, or using some outwardly incoherent form. Others were fools-for-Christ in order to endure humiliation and ignominy for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven.

There were such fools-for-Christ, popularly called blessed, who did not take on the podvig of foolishness-for-Christ, but due to their childlike simplicity that they retained all their lives, truly gave the impression that they were simple-minded.

If we unite the motives ascetics may have for taking on the podvig of foolishness for Christ, then three main points can be discerned: to trample down vainglory, which can easily arise with the practice of monastic asceticism; to emphasize the contradiction between truth in Christ and so-called common sense and norms of behavior; and to serve Christ with a particular kind of preaching, not by word or deed, but through the power of the spirit, dressed in an outwardly shabby form.

No one can ever say how long and why foolish-for-Christ has existed in the Church, or where clinical madness ends and the podvig of foolishness for Christ begins. I can only make a guess, a hypothesis: Foolishness for Christ is a rebellion against totalitarianism, against the violence of the powerful of this world in all its forms and manifestations. And the boundary line between foolish for Christ and madness, between reason and irrationality, is very blurred. The atheist communists persecuted the blessed fool-for-Christ Peter, and the militia beat him. He was locked up more than once in a psychiatric ward, but by God's Providence, each time he turned up outside free.

Sergei Geruk spoke with Archimandrite Avvakum (Davidenko)