On October 17, 2002, the Holy Synod of the Georgian Orthodox Church canonized the Venerable Hilarion the Georgian of Mount Athos (1776—1864). His life was intertwined with the upheavals of the nineteenth century: the dissolution of the Georgian Kingdom, its annexation by Russia, and the Greek Insurrection of 1821. Within these events St. Hilarion led a life that encompassed the fullness of Christianity. As a married priest he was the royal confessor, and later as a monk he witnessed to the Faith before the Muslims. He finally became a vessel of the Holy Spirit as a great ascetic and spiritual father on Mount Athos. Where he was called “St. Hilarion the Georgian[1]”

* * *

1. Childhood And Youth

St. Hilarion the Georgian.

St. Hilarion the Georgian. When Ise reached the age of six, Maria's brother, Hierodeacon Stephan (Stepane) arrived in Losiat-khevi. Fr. Stephan was a renowned ascetic, who before entering monasticism had lived at the royal court under the protection of Prince George Tsereteli. He eventually received permission to leave the palace, and entered the Tabakini Monastery.[3] After three years under the guidance of a virtuous elder, Archimandrite Germanus, he was tonsured and ordained a deacon. He spent the next six years living in the monastery while longing for seclusion. He was then allowed to live as a recluse, at first only for a few days at a time; and then after five years heentered a life of total seclusion.

Moved by divine zeal, Fr. Stephan yearned to train a disciple in the eremitic life. Arriving at his sister's house, he convinced her and her husband to dedicate their firstborn son to God's service. Taking Ise to his forest hermitage, the elder raised him for the next twelve years—teaching him silence, continence, prayer and the reading of the Sacred Scriptures.Since Ise was totally cut off from the world, the years of his youth were times of great spiritual warfare. Rarely did Fr. Stephan permit Ise to visit his parents or the monastery, and the boy learned early of the devil's malice. By means of various tricks, the demons tried to cause him either mental confusion or death itself. At night they would attack in the guise of thieves or call him with his mother's voice, reminding him of the home he had left. During the day they attacked him in the appearance of bears or other beasts in order to frighten him.

When Elder Stephan's repose drew near, he, knowing this in advance, counseled Ise to leave the hermitage after his death—for, living without a director, he might fall into the devil's nets. Fr. Stephan then went to the monastery, begged forgiveness and gave a last kiss to the brothers. He returned to his cell and after an illness of several days departed to blessed eternity.

The elder's death was a great loss not only for the brothers of the monastery but also for many laymen. In him they had lost a man of prayer, a counselor, and a comforter. Ise later testified that Fr. Stephan was a man of strict monastic principles, who had attained a high level of discernment in spiritual matters. For weeks at a time he would only eat cornbread with salt and water. At other times, he ate only a few vegetables. During Great Lent he would spend three days at a time in total abstinence. Many came to him for advice. To one layman who desired to become a monk he said, "If you wish to begin the monastic life, you must first cut off up to one half of all your whims and worldly predilections before the monastic tonsure, and then labor so that all traces of worldly life in you will be destroyed once and for all."

After the elder's death, Ise moved to the Tabakini Monastery. He lived there only a short time, as he zealously desired to continue his studies. Hearing that a school had been opened in Tbilisi, he secretly left for eastern Georgia. En route, he stayed with the Bishop of Nikozi, Athanasius. This holy man, after hearing of Ise's life and listening to him read from the Georgian prayer book, counseled him about his future: "My child, you won't learn anything in school like you have learned in the desert. So, return home, and through the prayers of your elder, the Lord God—Who has taught you these prayers—will guide you into such a state that you will be of benefit to God's Church and to your people." With the blessing of this man of God, Ise returned to his parents' house.

Ise remained with his parents for only a short time, before his father sent him to the palace in Kutaisi. Like an offering Ise was brought to the king for service. The king entrusted him to his attendant, Prince George Tsereteli, for instruction. The latter, seeing in him an inclination for the spiritual life, entrusted him for further schooling in the sciences to the well-educated Archimandrite Gerontius.[4] Fr. Gerontius strove most of all to develop in his pupil a love for prayer, and nurtured him in a strict monastic spirit. Ise would afterwards recall with wonder how the elder kept vigil, standing from Compline until sunrise, and would make him stand at prayer with him. Thus, they would pass the entire night in psalmody and the reading of prayers from the Georgian prayer book. Ise led an ascetic life with his teacher, living in total obedience to the elder.

Once in winter, Fr. Gerontius entrusted him to deliver a letter to a friend in Kutaisi, sending him barefoot through the snow. The letter reached its destination, and the man, struck by Ise's appearance, gave him two piasters, ordering him to buy leather sandals for himself. Returning with the sandals on his feet to his elder, he received a severe rebuke from the latter for his faintheartedness and impatience.

The elder also gradually taught his disciple abstinence, leading him forward little by little. Initially, he instructed him to abstain from food until the setting of the sun on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Later, he weaned him from tasting anything at all on these days.

At the same time, Fr. Gerontius educated him in secular studies:[5] calligraphy, grammar, arithmetic, etc. In such unremitting, sober labors, Ise spent three and a half years with the elder.

When Fr. Gerontius saw that the youth had become proficient in all his studies in such a short time, he sent him back to Prince Tsereteli for other general studies. The Prince kept Ise always by his side, taking him wherever he went. After a year, the Prince entrusted him to monitor the income and expenses of his retinue. He likewise entrusted him to sign all orders in his name, giving him his personal seal for this purpose.

2. In Service to the King

King Solomon II of Imeretia.

King Solomon II of Imeretia. King Solomon kept Fr. Ise close to himself, entrusting him to resolve the nobles' disagreements, which had previously erupted in violence. The responsibility of peacemaker demanded great tact and patience on Fr. Ise's part. This was so time-consuming that he was rarely able to see his wife. This grieved Maria greatly. Once she learned that her husband, returning from a routine journey to the estate of Prince Abashidze, had traveled straight to Kutaisi without informing her. Maria took this so strongly to heart that she lost her health and, after a six-month illness, reposed, having been married only two years.

About this time, relations between Imeretia and Russia reached a critical point. In 1801 the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti (eastern Georgia) had been annexed to the Russian Empire at the request of King George XIII (reposed December 1800) to protect the country from the Ottoman Turks and the Persian shah. The Russian government then initiated correspondence with the Imeretian king concerning the uniting of his nation with Russia. King Solomon II sought the counsel of his country's foremost nobles, and in 1804, due to pressure from Russia, he was left with little choice but to set forth the following: since the king did not have an heir to the throne, Imeretia would retain her independence until his death, remaining in brotherly relations with Russia as between two realms of the same faith. The Russian army had free passage across Imeretian territory to the Turkish border, and the Imeretian army was required to render them aid. The relations of the two countries were to be upheld in those sacred terms which are proper to God's anointed rulers and Christian peoples united in an indivisible union of soul—eternally and unwaveringly. But after the king's death the legislation of the Russian Empire would be introduced. The resolution was then sent to the Governor-General of the Caucasus in Tbilisi for forwarding to Tsar Alexander I.

Despite the general approval of the resolution by the king's subjects, one nobleman, Prince Zurab Tsereteli, began plotting how he could seize the Imeretian throne for himself. He first attempted to erode the friendly relations between the two monarchs by slandering each to the other. Unable to sow discord, he began a communication with the Russian governor-general of the Caucasus, Alexander Tormasov. Depicting the royal suite in the darkest colors to the governor-general, after repeated intrigues he finally succeeded in his designs. Eventually, the report reached the tsar. He, believing the slander, ordered Tormasov to lure King Solomon II to Tbilisi and escort him to Russia, where he would remain as a virtual prisoner.

The Bagrat Cathedral in Kutaisi.

The Bagrat Cathedral in Kutaisi. 3. Imprisoned in the Palace

After the king's death, Fr. Ise intended to set out for Imeretia (then annexed by Russia) no matter what the consequences. He informed all the courtiers, who numbered about six hundred men, and suggested that they follow his example. Many of them accepted his decision joyfully, but fear of the tsar's wrath hampered this plan. Fr. Ise reassured everyone, promising to take upon himself the task of mediating before the tsar. He immediately wrote out a petition in the name of all the princes and other members of the retinue and sent it to the tsar. The sovereign graciously received their petition, restored them to their former ranks, and returned their estates.

In May 1815, three months after King Solomon's death, Fr. Ise returned with the courtiers to Imeretia. There, he settled in his parent's home. Finally free from the responsibility of being the royal confessor, he began to seek a place suitable for a hesychastic habitation. He thought of making his abode near his native village, or in the wilderness near Tabakini Monastery, where he had spent the years of his youth. But not seven months had passed after his return to his homeland when the Imeretian queen, Maria, requested him to come to Moscow, where she had been brought after King Solomon's flight to Turkey. The queen felt that Fr. Ise as royal confessor was better able to inform her of her husband's last days. True to his duty, Fr. Ise immediately set out to inform the queen of everything that had come to pass. He presented the queen with a large piece of the Life-giving Cross that had belonged to King Solomon II, and the queen placed it in her house church. Esteeming Fr. Ise's devotion to her late husband, and, furthermore, not wishing to have a foreigner (a Russian) as her confessor, the queen retained the priest at her Moscow palace.

Upon Fr. Ise's arrival in Moscow, a new temptation befell him. The tsar desired to have him consecrated bishop of a large city. This was probably due either to his transforming the rebellious Imeretian noblemen into faithful subjects of the Russian Empire or to the recommendation of Queen Maria. Nevertheless, the loftiness of rank could not entice the soul of Fr. Ise, which yearned for solitude even while fulfilling his obedience in a Moscow palace.

Having settled in the palace, he soon beheld the great spiritual degradation of the religious and moral life of the courtiers—especially when contrasted with the piety that the former Imeretian kings and people had upheld. He observed that the queen and her court had forgotten their Christian duty, instead reveling in worldly amusements: failing to keep the fasts on Wednesday and Friday, incessant carousing, and outright profligacy as well. The queen herself served as an example of this, conducting herself as the court favorite. All this burdened Fr. Ise exceedingly, and all his exhortations and instructions were disregarded.

Despite his strict watch over himself, Fr. Ise too was infected by the worldliness of the court. Willingly or unwillingly he had submitted to the conditions of life in the ancient Russian capital: his table abounded with diverse dishes, he drank much wine and slept on a feathered bed. There loomed the even more serious danger of a deep and grievous fall. Fr. Ise was distinguished by his physical beauty: tall in stature, wide in shoulders, stately—a handsome man. His soul's beauty was reflected on his noble face, and involuntarily the eyes of many fell upon him. In piously disposed souls he evoked respect; but in passionate, sensuous people he roused impure lust. Fr. Ise came to experience all the savage attacks of the primordial enemy through the ladies and maidens of the court. Their immodest advances so constrained his modest soul that he firmly resolved to leave the court—he could find no other way of avoiding the pursuit of these women. Moreover, he came to understand that by himself he could not transform the morals of the court.

Battered from all sides, Fr. Ise repeatedly besought the queen to free him from the difficult life of the ancient capital so he could return to his homeland. The queen, however, would not hear of it. At times she dismissed the matter with a joke, and at other times she resolutely denied his request. Fr. Ise in turn firmly disclosed to her on many occasions that, if she would not release him voluntarily, he would leave secretly. At this the queen, smiling, would remark that this was not Imeretia, and such flights were impossible: in the first city to which he might come, the police would arrest him and return him to the palace. In this way three and a half years elapsed, which served as a mighty test for Fr. Ise's pious soul, a test incomparably greater than the seven years of wandering with King Solomon on foreign soil.

Remaining in such a desperate plight, Fr. Ise found rest for his soul only in prayer to the Lord and His Most Pure Mother. Pouring forth his afflicted soul, he entreated them to fulfill his long-awaited desire—to live as a recluse in the wilderness. Likewise he prayed to the Holy Great-martyr George, in whom he had conceived great faith while still in his parent's house, and who had already aided him many times in his life. About this time, Fr. Ise became acquainted with the archimandrite of Iveron Monastery on Mount Athos, then residing in the St. Nicholas Monastery in Moscow. This archimandrite would later reveal to the monks of the Holy Mountain who Fr. Ise really was, since on Athos he would conceal himself under the guise of a poor simple monk.

With each passing day Fr. Ise's sorrow grew. Once, in a frank conversation with Queen Maria's valet, a man deeply devoted to him, he revealed his heart's desire. The latter approved of his good intention and promised to help. Conceiving a plan, he informed Fr. Ise of it. Having prayed fervently, they went to Metropolitan Seraphim.[7] The Metropolitan often visited the queen and was well acquainted with both the valet and Fr. Ise. Coming to the Metropolitan, the valet told him that the queen had sent him to request the issuance of a passport for Fr. Ise, as he was going home to Imeretia for a while. The Metropolitan, without suspecting anything, immediately made the arrangements for the passport to be issued.

Winged by hope in the fulfillment of his desire, Fr. Ise appeared before the queen, and, as he had done many times previously, began to tell her that he was going to leave. The queen laughed at his words. When he said that he had already received his passport, she replied that she did not believe him, because without her permission no one would issue him one. With the words, "Farewell, I'm departing!" Fr. Ise left the queen and departed that very night. However, he did not travel to Georgia, knowing that the queen could easily find him there and summon him again to Moscow. Instead, he traveled to Odessa, and proceeded directly to Constantinople. His intention was to visit Palestine and Sinai, and to settle somewhere in those places where in ancient times Georgians had lived the ascetic life.[8] About Mount Athos, he knew almost nothing.

4. Arrival on Mount Athos

Iveron Monastery.

Iveron Monastery. Arriving on Athos, Fr. Ise settled in the Iveron Monastery. Although Iveron had been founded by Georgians and at one time had been filled with his fellow countrymen, he now found none. Not knowing the Greek language, he managed to communicate with several brothers in Turkish. Since those who knew Turkish were few, Fr. Ise spent the greater part of his time in silence. He explained that he was a Georgian by birth, a poor man, which his old, soiled clothing corroborated. He said that he had come to Athos to venerate the holy objects and to see the Holy Mountain. According to custom they led him to the guesthouse, where he spent a week attending church services and observing monastery life.

Silently walking around the monastery, Fr. Ise attentively observed the inner way of life of an idiorrhythmic monastery, but the idiorrhythmic rule did not appeal to him and he said to himself, "Although this is our monastery, yet it is not for me!" One morning he walked outside the monastery gates and noticed that several of the brothers were lifting sacks over their shoulders and leaving for somewhere. Fr. Ise learned from them that they were going to Dionysiou Monastery for their patronal feast, the Nativity of St. John the Forerunner, which was to take place the next day. When he asked if they would take him, they replied, "If you would like, let's go."

Traditionally, everyone who comes to an Athonite monastery for a feast day first goes to the guesthouse. Here everyone is treated to a small liqueur, a cup of Greek coffee, and cold water. Then the pilgrims proceed to the refectory for a meal before the vigil. For Fr. Ise, however, things turned out differently. While entering the monastery he lost his traveling companions in the crowd of people. They, forgetting that he was unfamiliar with the local customs, neglected to look for him. Fr. Ise had not eaten anything all day and was exceedingly hungry. Not expecting that someone would invite him to the refectory and, hearing that they were already ringing for the All-night Vigil, he went to church amidst a group of pilgrims. He assumed that, for the sake of the memory of the great prophet John the Baptist, it was a strict fast day in the monastery, and the brothers were also not eating anything.

The length of the service amazed him, for the night was past and the vigil continued on. It ended only two hours after sunrise. Fr. Ise pondered: Would they offer anything to eat? Would they continue fasting now, too?

But then Liturgy began. Only afterwards did everyone go to the refectory, and Fr. Ise followed behind everyone. The feast day served as a great spiritual consolation. He liked the order of services, the way of life of the monks, and the strictness and harmony in everything so much that he wanted to remain in the monastery.

On the third day of the feast the guestmaster asked Fr. Ise why he was not leaving with the others. He replied that he would like to spend more time at the monastery observing the rule of life, and the guestmaster told him he must obtain the blessing of the abbot to do this. Fr. Ise went to the abbot—who spoke Turkish well—and explained to him that he liked the strict order of Dionysiou and wished to live there and observe their life, for which he was now asking a blessing. If it pleased the abbot to accept him, then he was prepared to remain there permanently. Abbot Stephen, seeing his bodily strength, agreed to accept him, saying that he needed working hands. He gave him an obedience to work in the kitchen.

At Dionysiou Fr. Ise found his old friend, Fr. Benedict the Georgian,[9] who was living close to the monastery in a hermitage. During Great Lent in 1821 they received the tonsure to the great schema together. At the tonsure, Fr. Ise received the name of Hilarion. Although tonsured first, Fr. Hilarion always considered Fr. Benedict as his senior, especially in regard to ascetic labors. New monastic garments had been prepared for the tonsure, but Fr. Hilarion refused them and asked to be clothed in his tattered robes.

Besides laboring in the kitchen and refectory, Fr. Hilarion was given all the difficult obediences. He was sent to cultivate the monastery vineyards at Monoxilitis located not far beyond the boundary of Athos. He always chose those tasks which were most laborious and difficult there. At the vineyards he took the heaviest and largest shovel, embedded it deep in the ground, and dug in such a way that no one could imitate him. Likewise, he untiringly bore all his obediences in the monastery, being endowed by the Lord with both physical strength and zeal for ascetic labors.Even though he did not know Greek, the brothers loved Fr. Hilarion for his exemplary love of labor and his meek and ascetic life. Living in Dionysiou under the guise of a poor, simple Georgian and possessing absolutely nothing, Fr. Hilarion never locked his cell. Once, one of the brothers went into his cell during his absence and, seeing a tin container, became curious and opened it. To his utter astonishment he found a Russian passport and an imperial Turkish decree indicating that the bearer was a priest. He immediately told the abbot, who summoned Fr. Hilarion and asked him what he kept in the tin container. Fr. Hilarion replied that it was his passport. The abbot ordered him to bring the documents to him. Fr. Hilarion, hoping that no one knew how to read Russian and Turkish, brought them to the abbot. To his great sorrow, one monk read Turkish and was able to read the imperial decree. Thus, they all learned he was a priest. Fr. Hilarion persuaded the brothers not to speak to anyone of this.

Fr. Hilarion spent about two years carrying out difficult obediences with love and self-denial. However, he was troubled that, in not knowing Greek, he was deprived of hearing the word of God. His soul languished from not reading the Sacred Scriptures. Therefore, Fr. Hilarion decided to reveal his thoughts to the abbot and seek a blessing to go to the Iveron Monastery, where he would ask for a few of the many books in the Georgian tongue. The abbot blessed him, and Fr. Hilarion set out for Iveron in his customary old and soiled raiment.

Reaching Iveron, he stopped to pray before the wonderworking icon of the Theotokos.[10] It was evening then, and the senior brethren were sitting in the portico at the entrance to the monastery. Among them was that very archimandrite with whom Fr. Hilarion had become acquainted while still in Moscow. As soon as he saw Fr. Hilarion, he immediately recognized him. To the astonishment of everyone, he rushed up to him and began kissing his shoulders and hands, exclaiming all the while, "Oh! Oh! Papa Ise, Papa Ise! The holy confessor! The royal confessor!" Bewildered by such an extraordinary greeting, everyone stood up and approached the visiting monk. The archimandrite, holding Fr. Hilarion by the hand, introduced him to the fathers, saying, "This is Fr. Ise—the royal confessor, whom I had the pleasure of meeting in Moscow in the palace of the Queen of Imeretia." The astonished monks led him into the monastery, where everyone was amazed at such an unexpected revelation, especially those brethren who had seen him as a poor newcomer two years earlier. The archimandrite led Fr. Hilarion to his quarters and for three days would not let him go, begging him to remain in their monastery. He offered Fr. Hilarion the best cells at the monastery's expense with attendants. But being convinced that Fr. Hilarion would remain unbending, he gave him the Georgian books and sorrowfully let him depart.

With a sack on his shoulders, Fr. Hilarion returned to Dionysiou, not suspecting that his true identity had already become known there. The rumor that a royal confessor was hiding at Dionysiou under the guise of a simple monk had already spread across Athos. At the monastery entrance the porter respectfully prostrated before him, greeted him as an elder and informed the abbot. The latter met him with outstretched arms, reproaching him in a brotherly way for not revealing his identity earlier. Fr. Hilarion, troubled by such a reception, said, "My visit to Iveron was not to my benefit. It would have been better if I had not gone there, for I came to the Holy Mountain to weep over my sins, and it was more peaceful in ignominy for me than it is now."

The abbot no longer wished to allow him to fulfill his previous obediences, but asked him to take upon himself the duty of confessor. Fr. Hilarion, however, resolutely refused this, and insistently asked that they not deprive him of the opportunity to serve the brothers. He proceeded to the kitchen, but soon departed, for the respect of all followed him everywhere. The brethren would not let him fulfill his former difficult obediences, but attempted in every way possible—lifting loads, carrying water and firewood—to forestall the elder. This came to an end when he left the kitchen and took up his abode in a secluded cell near the monastery.

5. Confession of the Faith

In 1821, as a result of the Greek Insurrection, the Turks began a series of reprisals and persecutions. Christian blood flowed like a river, for the Turks wanted to put down the uprising and suppress the revolt by force of arms. As Athos had also supported this uprising, it too was subjected to the grievous consequences of war. In 1822 the ruler of Thessalonica, Abdul Robut Pasha, marched toward Athos from Cassandra with a large army and made camp at Kumitsa at the Isthmus near the border of Athos.

The pasha then sent an order that the superior of every monastery must appear before him in repentance. In case of their refusal, he vowed to occupy the Holy Mountain and destroy the monasteries. The abbots, knowing the Turks' cruelty and fanaticism, evoked at the time by the uprising, decided not to appear before the pasha, well aware that they would not remain among the living.

Abbot Stephen of Dionysiou Monastery, fearing to appear personally before the pasha, asked Fr. Hilarion to take his place. Fr. Hilarion gladly agreed to his request, saying, "I am not afraid of the Turks!" But the abbot warned him that this time the matter was not so simple. When the envoys would depart to meet the pasha, then all the brothers would leave the monasteries, taking with them all the valuables and holy objects—for which they had boats waiting. This would not go unobserved by the Turks, and they of course, in revenge for this trickery, would kill the envoys. Consequently, certain death awaited him. Fr. Hilarion exhibited his complete willingness for anything, as he had long desired to suffer martyrdom for Christ. The abbot said, "Now is the most timely opportunity—take advantage of it for the common good." Two others, Hieromonk Panteleimon and another monk, accompanied Fr. Hilarion.

Reaching Kumitsa, the envoys presented themselves before the pasha with a letter from the Holy Community[11] in which the representatives of the monasteries were named. The pasha began to read, and when he reached the name of Fr. Hilarion the Georgian he stopped, glanced at the fathers, and asked which one was the Georgian. Then, addressing Fr. Hilarion in Georgian, the pasha discovered that Fr. Hilarion lived in the province neighboring his native land, Abkhazia. In fact they had lived in adjacent towns, and Fr. Hilarion knew the pasha's home quite well. The pasha turned out to be the son of an Orthodox priest. In his youth he had been taken captive, sold to Turks and converted by them to Islam.

"So, we're fellow countrymen," said the pasha. "How long have you lived here and why did you come?"

The elder answered, "I came in order to pray to God, and I've lived here three years."

The pasha then began to speak to Fr. Hilarion in Turkish: "Why did you come to join these thieves? Why have you, an honorable and noble human being, become mixed up with these scoundrels?" Mercilessly upbraiding Athos and its monks, the pasha meanwhile tried to persuade Fr. Hilarion to abandon the Holy Mountain, presenting him with many arguments. Among other things he related that he had come with the intention of killing all the monks of Athos, but pitying him as a man of nobility and a compatriot, he did not want to subject him to such a lot. Attempting to convince Fr. Hilarion to abandon Athos, he offered him his home near Thessalonica, every protection, assistance, and money from the sultan to settle wherever he liked—even in his homeland. Fr. Hilarion, however, replied that he had come to Athos to save his soul and, besides, he needed nothing.

The pasha again attempted to persuade him to abandon Athos—this "nest of prodigality and thievery." But Fr. Hilarion rejected this proposal and said about the Athonite fathers: "No, these are honorable people and true servants of God. Look how dishonorably you have proceeded. You have forsaken the true Christian Faith. Now, to crown your grievous errors and perdition, you are marching armed with weapons against Christ's followers, spilling their innocent blood and capturing Christian youths by force, so as to lead them into apostasy—into the same destruction." The pasha in reply implicated the Athonite monks in the uprising against the Turkish authorities, and in inciting all the inhabitants to this end. Regarding the capture of the Athonite youths, he said that they could serve the government with benefit and need not be buried in the wilderness.

Then the pasha began to blaspheme the Orthodox Faith, stating, "What folly it is for a Christian to believe that a virgin gave birth to God. How could a human womb contain God, and having given birth remain virgin?" To this Fr. Hilarion objected, "You do not understand the mystery of the Incarnation of God the Word. The understanding of this is the gift of God, and whosoever has it understands how a virgin can give birth to the Redeemer of the world! But, I will explain it to you." At these words the pasha was moved to wrath and began to pace quickly back and forth before his tent. The remaining monastery envoys, understanding that this conversation would not lead to any good, inconspicuously moved Fr. Hilarion back and quietly said to him, "Now is not the time for these arguments, because you might anger the pasha and provoke him to the extent that not only you, but all who remain on the Holy Mountain will be put to death or torture. If you don't pity yourself, then at least have pity on the holy fathers of Athos who will meet such a grievous fate." Having convinced Fr. Hilarion by their words, they spoke with the pasha and handed him the gifts they had brought.

The pasha allowed Fr. Hilarion to go wherever he pleased, but he incarcerated the remaining representatives in the prison in Thessalonica. He sent the Athonite youths also to Thessalonica for preparation to embrace Islam—there were more than three hundred of them. The pasha himself went to Njegosh, a city beyond Thessalonica, where a revolt had recently taken place; there he killed a multitude of Christians.

Upon returning to Athos, Fr. Hilarion grieved that he had not successfully countered the pasha's blasphemous words. The latter remained as it were the victor. He sorrowed even more upon hearing of the pasha's bestial deeds in Njegosh. Aflame with godly zeal, he implored Abbot Stephen to permit him to go to Thessalonica for a talk with the pasha. The abbot asked him if he had within him enough courage and strength, and if he was capable of enduring prolonged torture and death itself. Fr. Hilarion replied that he was ready for anything with God's help; even in Kumitsa he had sought this, having begun to reproach the pasha, but they would not let him finish. Abbot Stephen unhesitatingly blessed him, wishing him the aid of the Lord and the Theotokos. Having asked the prayers of the brothers, Fr. Hilarion went on foot to Thessalonica and arrived during the Muslims' Ramadan, during which the Turks fast by day but make merry after sunset.

At the gates of the pasha's residence, the elder asked the guard to inform the pasha that Hilarion the Georgian wished to speak with him. Inside, the chief Turkish functionaries had gathered as well as several foreign dignitaries: English, French, Jewish, and Armenian. Evening was close and they would soon begin their banquet. When they informed the pasha of Fr. Hilarion's arrival, he said for all to hear, "Oh! It's that priest whom I convinced of the emptiness of the Christian belief, and he has come here to receive the faith of the great prophet. Summon him!"

At the summons, Fr. Hilarion entered. Seeing the pasha seated on a divan and all his functionaries standing before him, he paid him his due respect. The pasha with joy addressed him, "Oh! Papa Hilarion! Welcome! You have obviously come as a consequence of our conversation about the faith?" "Yes," replied Fr. Hilarion, "it was chiefly your words that caused me to come straight here to speak with you in detail, since in Kumitsa they wouldn't let me finish our conversation. For me it is a pleasure that at this time I find the first citizens of Thessalonica here with you." "It's my pleasure also," said the pasha, "to meet and speak with you on this day of our feast."

Then he sat Fr. Hilarion beside himself on the divan while all the respected citizens continued to stand before them. Fr. Hilarion then began where their conversation had been interrupted: "You expressed doubt as to how the Virgin could give birth to God, and having given birth, could still remain virgin? So I will explain this to you, for both you and your prophet Muhammad say that Jesus Christ was born from the Virgin, was born from a seedless conception, and therefore His Nativity as the true God is inscrutable. He is the true God and for the salvation of mankind He took upon Himself flesh that He might redeem the fallen race of mankind from the curse of death."

The pasha, realizing that the elder was steadfast in all his convictions, started an argument with him, during the course of which Fr. Hilarion brought up the pasha's cruelty in Njegosh and said, "Don't you fear God, torturing Christians innocent of any wrongdoing? You were born of Christian parents, and yet you act so bestially so as to quell the torment of your conscience because of your apostasy from Christ."

The pasha, laughing, replied, "Just the contrary, I was so happy that I was delivered from the ludicrous faith of the Christians, that later, when I was already a pasha, and when the man who had stolen me from my parents and sold me to the Turks came to me, I gave him a baksheesh [reward]. I thanked him that he had done me a great service. If your faith was true and pleasing to God, then the Lord would not have given you into the hands of your enemies and they would not be treading you down always and everywhere."

Fr. Hilarion objected to these proud words: "You understand everything incorrectly, Pasha. Does a father not take a rod to chastise his beloved son when he misbehaves? But he does this not to turn his son away from his heart, but to correct him. When he sees that the child has corrected himself, then he breaks the rod and casts it into the fire. Likewise, the Lord has used you to scourge us for our sins, desiring and seeking our amendment. You are an iron rod in God's right hand, and when the Lord sees our amendment, He will cast this rod into the place appointed for it, as a thing no longer needed."

Then he began to upbraid the pasha for the youths he had captured on Athos. The pasha continued to listen to his reproaches without wrath, but when the day reached evening the elder was unable to speak any longer. The pasha offered him lodging, but Fr. Hilarion, seeking not repose but martyrdom, refused the pasha's offer. He passed the entire night in the courtyard, hoping to attain his goal on the following day.

Three days passed in this way, with the elder reproving and reviling the pasha in the hope of compelling him to order his martyrdom. Still, the pasha remained unmoved. Fr. Hilarion spent the second night in the home of a certain God-loving Christian named Spandoni, who together with his whole family showed the elder warm hospitality.

On one of these nights, while Fr. Hilarion was praying in preparation for his martyrdom, an armed Turk entered the house. At that time it was permissible to kill any Christian. Therefore, the Turk unsheathed his sword and wanted to strike the praying elder, saying, "I'll cut you up." However, brandishing the sword, he was unable to carry out his intention—his hand was as it were petrified, and somehow restrained. Holding the sword for a long time in the air, he was only able to lower it when he decided to return the sword to the scabbard without harming the elder.

On the fourth day, Fr. Hilarion tried even harder to anger the pasha. He began to speak about the falsehood of Islam and of its founder Muhammad. Calling him a deceiver, he stated that not only had he perished, but also everyone who believes in him will perish.

"Where do you think we will go?" the pasha asked, laughing.

"The same place where your Muhammad will go!" answered the elder.

"And where is that?"

"To hell!" answered Fr. Hilarion, "—and you along with him!"

"Who, according to you, will be saved and go to heaven?"

"Only those who truly believe in God, who are found in the bosom of the Orthodox Faith of Christ; beside this, everyone—Jews, Armenians,[12] Catholics and Protestants—will be condemned to torment."

Then everyone who was in the room cried out in wrath, "Death to him!" At these cries it was impossible for the pasha to remain indifferent any longer. He did not desire the elder's death, but in order not to be reckoned an apostate from Muhammad's law he ordered Fr. Hilarion's head to be cut off. "Look, you have brought this upon yourself; I no longer have any power to defend you. Because of your daring words your head will roll from your shoulders!"

Fr. Hilarion, baring his head, lowered it and said, "Well, cut it off! I do not fear to die for the truth. He held his head that way until the executioner came to lead him to the place of execution.

While preparations for carrying out the sentence were taking place a pair of Abkhazian bodyguards, whom the pasha loved for their faithfulness and devotion, came to him. He told them of his decree to execute the Georgian priest. Dumbfounded, they clasped their hands, crying out, "This cannot happen, this cannot come to pass! This is a disgrace to us. We would never be able to appear in the city. Hardly had one of our compatriots appeared in this region, they will say, and they executed him. This will be our eternal shame." Not wishing to grieve his beloved friends, the pasha gave Fr. Hilarion over to their disposal.

The people streamed after Fr. Hilarion and the executioner: Christians and Turks and a multitude of Jews. Walking along the streets, the crowd continued to grow, and at the central square there was such a crowd thronging them that it was impossible to proceed. Fr. Hilarion walked firmly. Neither on his face nor in his movements was a shadow of fear to be seen. Whispering his prayers, he appeared joyful, as if walking to a wedding feast. The bodyguards, having received the pasha's permission, hurriedly went to the square. Squeezing their way through the crowd, they met Fr. Hilarion at the place of execution. In the name of the pasha they took him from the executioner's hands and led him away, the people following after them.

Fr. Hilarion thought that they had changed the place and manner of his execution and were leading him to the gallows, and thus he obediently walked behind his guides, continuing to offer prayer. But the farther they led him, the more bewildered he became. They had gone quite far; they had walked along the streets and through courtyards. In every square he expected that there his punishment would be meted out. In the meantime they led him ever further and further away in the direction along which he had come from Athos. The people, who had been persistently following him, were stopped by the sentry at the city gates. The Abkhazian officials led Fr. Hilarion out of the city, and when he was already far from the city, one of them hit him on the back of the head with such force that he nearly hit the ground face first. They said to him, "Get going to your Athos, Priest, and don't show your face here again."

Getting up, Fr. Hilarion slowly walked a short distance and glanced back. Both officials stood on the same spot and, threatening him, cried out that he should walk without looking back. Walking quite far, he looked back one more time and saw them standing on the same spot menacingly shaking their fists at him. Soon they were no longer visible. Then Fr. Hilarion, crossing himself, sighed and said, "I, the wretched one, am not worthy that the Lord would receive from me the sacrifice of martyrdom." He quietly started down the road for Athos. Remembering the love of that Christian who had given him lodging, he decided to return and thank him for the shelter and his generosity. Spandoni, meeting the elder again, would not let him go on foot to Athos, but gave him a horse and a guide.

6. Ministry to the Imprisoned

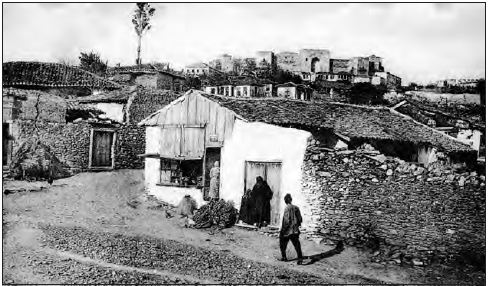

Old Thessalonika.

Old Thessalonika. The prisoners were languishing from hunger and thirst. When Fr. Hilarion drew close to the window, the hand that had waved at him showed itself again, holding a cup. A voice from the prison asked him to bring water. Fr. Hilarion fulfilled the man's request, but just then another hand appeared with a cup and the same request, then one hand after another reached out. The elder fulfilled everyone's request joyfully and, when he learned who was being held captive there, he decided to stay and serve the prisoners.

He dismissed his escort, sending him back with the horse. He reasoned that the Lord had left him among the living precisely that he might minister to these unfortunate ones. Every day the elder came to the prison and brought them what they requested: bread, water and other food.

One of the Turkish guards, noticing this, wanted in his wrath to kill Fr. Hilarion. The elder, not being frightened in the least, was ready with joy to meet death at the hands of the angry Turk. But about the same time, the other guard awoke and stopped him with these words: "Don't touch him, let him bring things. Look, neither you nor I nor any one of us has given them bread; we were not posted to starve them to death, but only to guard them. So if he has such fervor, let him feed them and let us not hinder him."

Fr. Hilarion spent six months in this manner helping the prisoners. In a separate ward in the same prison, two prisoners hung from ropes. One was a Christian and the other was a rich Turkish banker, from whom the pasha, by trial and torture, was trying to extort money for the needs of the government. These two prisoners had been hung by the hands and feet so that at the slightest movement the ropes would swing from side to side. Special guards were assigned to them, who kept their guns always loaded and their swords bared, not allowing anyone to come close to the unfortunate ones. They were given neither food nor drink, as they had been sentenced to starve to death in this frightful manner.

It was a warm day and the men suspended in the air were tormented by unbearable thirst. Their lips were parched and cracked. Fr. Hilarion, who often happened to be in the prison, concentrated all his attention on how he might help these two unfortunate men—but any attempt might cost him his life. Filling a flask with water and grabbing two large pears, Fr. Hilarion began to wait for an opportune moment to approach them. Then, at one point he noticed that both sardari [guards], who stood with bared swords and loaded guns, had leaned back against the wall and fallen asleep. To everyone's astonishment, the elder quietly made his way between the guards without waking them—despite the narrow passage. Approaching one of the suspended men, he poured a little water down his throat, then gave a little to the other, and having repeated this three times, he placed in the mouth of each a pear. The Turkish banker, seeing the elder's self-denial, said, "May Allah reward your good deed! But get out quickly so that the guards don't cut you to pieces." All the prisoners watched Fr. Hilarion in trepidation. Having accomplished this task, the elder hastened to depart. Returning past the guards, in spite of his caution, he nevertheless bumped one of the sleeping guards and they both awoke. But the Lord, who had brought sleep upon them, wondrously protected Fr. Hilarion: for having awoken and seen the elder's action, they remained immobile. Standing there stupefied, they did nothing to the elder. This act of his saved the unfortunate men from death, sustaining their vital strength.

After the elder's departure for Athos, a relative of the Turkish banker went before the pasha and obtained his release. The banker told everyone about the elder's deed and said, "Point him out to me, give him to me! I will gild him, I will cast his image in gold and bow down before him as my savior!"

Soon after this incident, Fr. Hilarion came to the prison to part with his friends, informing them that on the previous evening he had been informed by God to abandon his ministry to the prisoners and set out for Athos. He would never have left of his own accord, but, obedient to God's decree, he had to go. He found a man to replace him in serving the prisoners, and the God-loving Spandoni agreed to pay for his labor. Fr. Hilarion explained his work to him and, having parted with everyone, set out on his way. The day after the elder's departure, everyone learned that the pasha had ordered the executioner to cut off his head. Then all the prisoners glorified God, Who protects His servants—and their sorrow over the elder's departure was turned to joy.

From: The Orthodox Word, Nos. 23—231. (Published with permission.)