Knowledge uncurbed by the fear of God brings arrogance. —St. Maximus the Confessor

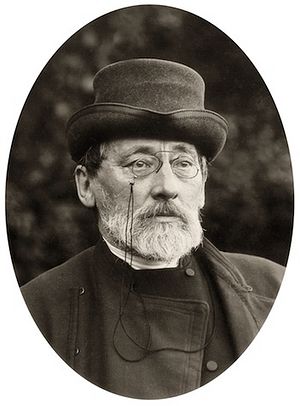

Konstantine Leontev.

Konstantine Leontev. Konstantin Leontiev was by no means an "ordinary" man: he was a diplomat, a doctor, a philosopher and man of letters. Nevertheless, his spiritual path—its general contours—is familiar to many of us, especially converts, and by examining his progress we may well assist our own. The following account is based in part on a chapter in I. M. Kontzevitch's Optina Pustyn and Its Era, and owes a still greater debt to the research of rysasaphore nun Natalia, whose article, "The Salvation of the Soul or Earthly Good," appeared in a recent issue of Orthodox Life (Russian edition) in recognition of this year's [1991] one hundredth anniversary of Leontiev's death.

The beginning of Leontiev's spiritual journey consciously began with his conversion, which came when he was already in the flowering of his adult life. As he himself describes in a letter to a friend, July 1871, he was that summer in Thessalonika when he fell ill with cholera. The, disease brought him to death's door. "At that time I was not thinking about the salvation of my soul (for faith in a Personal God came to me much more easily than faith in my own immortality); and I, not generally given to fear, became terrified at the thought of physical death." A monk from Mt. Athos had brought him an icon of the Mother of God. In looking at it, Leontiev continues, "I suddenly, momentarily believed in the existence and power of this Mother of God, believed so tangibly and strongly as if I were seeing before me a living, real and familiar woman, very kind and very powerful, and I exclaimed:

"Mother of God! It's early for me to die! I haven't yet accomplished anything worthy of my talents, and I've led an extremely promiscuous and utterly sinful life. Raise me up from this bed of death. I'll go to Athos, prostrate myself before the elders and beg them to turn me into a simple and genuine Orthodox Christian, who believes in Wednesdays and Fridays, [Intellectuals commonly scorned observance of fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays] and in miracles; I'll even become a monk."

In another letter he wrote: "For the first time I felt a hand over me from above, and I wanted to submit myself to this right hand and find in it support from the fierce internal storm; I sought only the forms for entering into communion with God. I went to Athos to try to become a genuine Orthodox Christian, in order that the strict elders would teach me to believe. I was prepared to submit to them my intellect, my will."

Following his miraculous recovery, Leontiev fulfilled his promise to the Mother of God and went to Mt. Athos. The elders, however, Frs. Jerome and Makary, did not agree to tonsure him, judging this to be premature. They undoubtedly foresaw that after the initial blaze sparked by his conversion had subsided, Leontiev would have great difficulty submitting to the rigors of monastic discipline. An avowed aesthete, he had been a man of the world for many years, and before him lay an arduous life-long struggle to free himself from its entanglements.

Leontiev's battle was fought on two fronts. In both cases it was intense, inasmuch as sinful habits and passions had had time to take root and mature. First, he had to war against "the lust of the flesh and the lust of the eyes." As he himself admitted, he had led a thoroughly immoral life and had become "a real profligate—to the point of refinement." Second- ly-and this was even more difficult—he had to war against intellectual pride. Kontzevitch describes Leontiev as "a man of a uniquely profound and brilliant intellect," and quotes another writer as saying that he "had an unusually independent mind, one of the most independent minds in Russia; it wasn't tied to anything."

Konstantin Leontiev as a young man.

Konstantin Leontiev as a young man. In battling against pride, the Holy Fathers recommend using its opposing virtue - Humility. Intellectual pride, however, is extremely stubborn. Looking back at his conversion, Leontiev wrote, “At that time I lacked sufficient grief. I hadn’t a shadow of humility; I believed in myself. I was much happier then than in my youth, and for this reason I was very self-satisfied…”

If the path of humility was at least temporarily closed to him, what means did Leontiev have to conduct the necessary warfare? He had a well-disposed will and the gifted counsel of Elder Ambrose, for a sincere desire for the Kingdom had led him to the famed Optina Hermitage, which earlier had similar- ly attracted other intellectual greats-Gogol, Kireyevsky, Dostoevsky. He also admitted being helped by "a long-standing philosophical antipathy for the forms and spirit of the new European life on the one hand, and on the other—an aesthetic and childlike sort of attraction for the outward forms of Orthodoxy." But Leontiev's principal ally in the spiritual arena was the fear of God.

Just as there are different kinds of love, and different degrees, so are there different kinds of fear. Leontiev's spiritual journey was launched by the fear of death. Reflecting on his conversion, he wrote: "The unexpected moment finally came when I, until then quite bold, felt an unfamiliar terror, not simply fear. This terror was at one and the same time a terror of sin and a terror of death. Never be- fore had I experienced either....I began fearing God and the Church. In time the physical fear disappeared, while the spiritual fear remained and kept increasing." It was Leontiev's opinion, writes Sister Natalia, that only genuine fear—not physical, bodily fear, not fear of the loss of temporal goods but fear of the destruction of the soul, total annihilation, disappearance into nonexistence-~nly through this kind of fear can an intellectual be led to faith.

Critics charged that Leontiev placed excessive emphasis on fear—at the expense of love, thereby distorting Christian teaching. However, according to the Holy Fathers, no one can reach love without fear. "Fear," writes St. Isaac the Syrian, 'leads us aboard the ship of repentance, takes us across the fetid sea of life and guides us to the divine harbor which is love.” And St. John Climacus writes, “The growth of fear is the beginning of love." Leontiev progressed beyond the primitive fear of death to faith and fear of God, from fear of divine retribution to fear of offending God—out of love for God. 'The believer fears God," explains Russian philosopher Prince Trubetskoi, "not only when he recognizes that he has transgressed His truth, but when he submits to Him with faith and love. For the fear of God is revealed in obedience, humility and prayer more purely and better than in the gnawings of one's conscience. The fruit of fear of God is love."

Leontiev did eventually become a monk; Elder Ambrose tonsured him in 1891, with the name Clement, in memory, no doubt, of Leontiev's dear friend, Optina monk Fr. Clement Sederholm. Knowing that his spiritual son was incapable of adapting to Optina's ascetic life, Elder Ambrose sent him to Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra. In parting, he consoled Leontiev, saying, "We shall soon see one another." Indeed. The Elder reposed October 10, 1891, and just a month later, on November 12, Leontiev joined him in the world beyond the grave. He died of pneumonia.

God alone knows how far Leontiev advanced towards that perfect fear which is, as one Holy Father stated, "equal in power to perfect love." It was, however, Leontiev's hope that in reading about his conversion, other intellectuals "would likewise not lose hope for finding the right path.” He himself pointed the way. As Archimandrite Constantine (Zaitsev) wrote: “Leontiev’s achievement lies in that fact that he says, as it were, ‘avoid those who, with words of love on their lips, steer you away from the Church, and learn instead to fear, i.e., renounce…self-assurance, reflect upon death and what awaits you after death, and, without clever philosophizing, freely, joyfully give yourselves over to the Church’s guidance. Only in this way will you attain salvation; only in this way will you learn to truly love.”