St John (Maximovich) of Shanghai and San Francisco has left us an exceptionally helpful sermon on the Gospel reading for this Sunday that helps put it into historical context. I excerpt the first two paragraphs:

Who was Zacchaeus? He was a leader of the publicans—"the chief among publicans." The customary comparison between the humble publican and the proud Pharisee often blocks the true meaning of these two images in our minds. However, to understand the Gospel correctly, one must picture them clearly. The Pharisees were truly righteous men. If on our lips the name "Pharisee" sounds as condemnation, in the days of Christ and during the first decades of Christianity this was not so. On the contrary, the Apostle Paul triumphantly confesses before the Jews, "I am a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee" (Acts 23:6). And then, to Christians, to his spiritual children, he writes, "I am of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, an Hebrew of the Hebrews, as touching the law, a Pharisee" (Phil. 3:5). And besides the holy Apostle Paul, many Pharisees became Christians: Joseph, Nicodemus, Gamaliel. Pharisees (in ancient Hebrew "perusim," in Aramaic, "ferisim," which means "other"—" the separated, the different) were zealots of the law of God. They "rested upon the law"; in other words, thought on it constantly, loved it, strove to keep it exactly, preached and interpreted it. And the reason for the Lord's accusation against the Pharisees is found in that the Lord warns them that their entire labor, their truly virtuous endeavors, are made worthless in the eyes of God, are turned into nothing and they obtain condemnation from the Lord and not blessings, despite their superiority and the righteous deeds they performed, because of their proud self-exaltation, and above all, their judgment of their neighbors, of which the Pharisee of the parable gives a clear example, saying, "Lord, I thank Thee, that I am not as other men" (Lk. 18:11).

On the other hand, the publicans were truly sinners, who broke the fundamental commandments of the Lord. Publicans collected taxes from the Hebrews for the Romans. One must remember that the Jews, well conscious of their special position of being divinely chosen, gloried in the fact that they were "Abraham's seed, and were never in bondage to any man" (Jn. 8:33). And now, as a result of well-known historical circumstances, they found themselves under submission; subjects to a proud, coarse, "iron" race of pagan Romans. And the yoke of this submission was being pulled tighter and tighter and was beginning to be felt more and more. The most tangible and obvious sign of the submission and subjugation of the Jews to the Romans was the payment of every imaginable tax and tribute by the Jews to their conquerors. For the Jews, as for all ancient people, paying tribute was mainly a symbol of subjugation. And the Romans, not at all abashed before a conquered people, roughly and decisively demanded of them both customary and additional taxes. Of course the Jews paid with hatred and disgust. Not in vain, desiring to compromise the Lord in the eyes of His people, did the Sadducees ask Him, "Is it lawful to give tribute to Caesar?" (Mt. 22:17). They knew that if Christ would say that one should not give tribute to Caesar, it would be easy to accuse Him before the Romans, and if He would say that tribute should be paid, He would hopelessly compromise Himself in the eyes of the people.

Turning to the spiritual dimensions of today's commemoration, here is an excerpt from another homily on this Sunday, this one given by the late Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of Sourozh:

Vanity is that condition of our soul, that miserable condition of our soul, in which we are afraid of human judgment, in which we derive our sense of worth from the judgment of those who surround us, and indeed it is vanity, because the things for which we are praised are vain, empty, unworthy of the greatness of man. And also, for praise we do not turn to those people capable of a sound and at time severe judgment; we turn to the peoples who are ready to offer us the praises which we want. This makes these praises doubly vain, its substance is naught, and the people from whom we receive it are also empty, in our own eyes, until they speak of us good. St John Climacus says that vanity is the attitude of one who is afraid of men and is arrogant before the face of God, who thinks God's judgment matters little, provided that he has the approval of those who surround him.

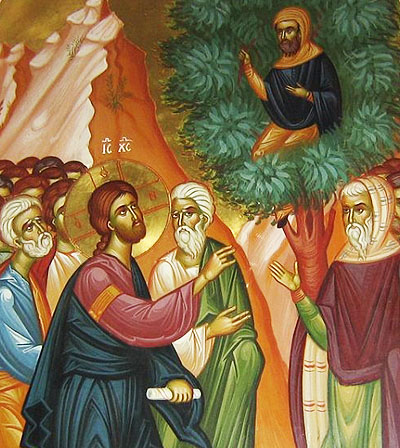

Is that not a true description of the way in which we stand in life, in the way in which we are prepared to forget the judgment of God provided we feel supported by the judgment of men? And what is the way then? Zacchaeus shows us one way: care nothing about the judgment of men because the judgment of God, the presence of God, or perhaps the judgment of one who will not praise us but is a person of integrity and of truth matters more. Zacchaeus did not know Whom Christ was and that He was the Son of God become the Son of man, but he knew that Christ was a man of integrity and he wanted to see Him, to meet Him face to face.

But then there are also two other ways of shaking off the fear of man, this dependence upon human's judgment at the cost of our own wholeness. St John Climacus says to us that the way to get rid of vanity is humility; St Isaac of Syria strangely says the way is also pride, and both are true, only that the one will give us life and the other will give us death. If we choose the way of pride we will assert ourselves arrogantly, not only in the face of men, but also in the face of God; our own judgment shall be the only thing that shall count, and then we will find death at the end of the road. The way of humility is that of bowing before the judgment of God. If we are incapable of soaring Godwards, lie before Him like the parched earth is before the face of the sky, abandoned, helpless, thirsty, hungry, longing, desperate not to be able to achieve what we wish to achieve, this is the beginning of humility.

But even that may be too much for us, even that may be too difficult for us because we are not used to let go, to abandon ourselves, offer ourselves to an act of God. Then we can begin to overcome vanity by gratitude. Whenever we discover that there is in us a moment of vanity, let us ask ourselves: why? Very often, it is because we have, inadvertently quite often, said the right thing, or inadvertently done the right thing; we can then turn to God and thank Him that He gave us the opportunity, that He gave us eyes to see the need, ears to hear a cry, a mind to understand, a heart to respond, good will to bring us into motion and the mean to do the right thing. Is not that reasons enough for us to be grateful, do we not know, all of us, from experience that it is not the need that will call out of us always, inevitably the right response? How often there is a need and our heart is parched, and cold, and indifferent? How often someone cries for help and we understand nothing, how often our heart has been stirred and our mind began to understand, but we are not used to compel ourselves and our will wavers, and wavers too long, until it is too late. And we could go on describing our condition in many more details.