SOURCE: The Copenhagen Post

Last year marked the 520th anniversary of the start of official diplomatic relations between Russia and Denmark, which began with the signing of the Love and Brotherhood Treaty in 1493.

However, strong ties between the kingdom of Denmark and the Moscow Tsardom had existed long before, dating back to the 1116 union of Knud Lavard and Ingeborg of Kiev, a Russian princess who would go on to mother one of Denmark’s most noteworthy Danish monarchs, Valdemar the Great, who would in turn go on to take a Russian bride himself, Sofia of Minsk, in 1157.

The unions meant that when the countries united once again seven centuries later with the marriage of Princess Dagmar to the future Emperor Alexander III in 1866, it was with good precedent.

From the Dagmar Cinema in the centre of Copenhagen (originally a hotel and theatre until it burned down) and the Dagmar Spring in Källviken in nearby Sweden, to Ingeborgvej in the suburb of Glostrup, these matriarchs of European aristocracy are remembered fondly to this day as an example of the strong ties between the countries.

Ingeborg of Kiev

Born in approximately 1100, Ingeborg of Kiev was the daughter of Grand Duke Mstislav, the son of Vladimir Monomakh, the grand duke of Kiev, and Christina, a Swedish princess who was the daughter of King Inge I.

It is believed she was originally called Irina, but changed her name when she married, adopting part of her grandfather’s. Her 1116 marriage to Knud Lavard, the prince of Schleswig and South Jutland, plunged her into a struggle for the throne that endured over long periods of the 12th century in Denmark.

The Danish history books remember her as a faithful companion and advocate of her husband’s claim to the crown, but beyond a poetic description of her by the envoy dispatched to Kiev to ask for her hand in marriage, which dates back to the 13th century, little else is known about her.

She had already given Knud Lavard three daughters by the time she fell pregnant with a son, but he didn’t live to see his birth as he was murdered by his cousin Magnus in 1131.

Their son was named Valdemar in honour of his great-grandfather on his maternal side, Vladimir Monomakh, so not only was Ingeborg the matriarch of a royal dynasty, she was responsible for introducing one of this country’s most popular royal names.

Despite her importance, there are no mentions of Ingeborg after 1137. Some sources suggest that she returned back to her home country with all four children. Others claim she left the future king Valdemar the Great in Denmark with a wealthy and powerful family, who he stayed with until he was grown up enough to claim his rights to the Danish crown.

Sofia of Novgorod

As the wife of Valdemar the Great, Sofia mothered two future Danish monarchs: King Knud VI of Denmark (reigned 1182-1202) and King Valdemar II of Denmark (1202-1241). And crucially for her husband, she was also the half-sister of her husband’s predecessor, King Knud V, the son of Magnus, who had arranged the murder of Valdemar’s father.

Although Sofia had been betrothed to Valdemar for three years, their eventual marriage in 1157 was made in haste out of strategic necessity as her husband, the then ruler of Jutland, sought to solidify his claim to become king of all Denmark following the treacherous murder of Knud V by Svend.

Both men were his cousins, and earlier in 1157 the three had divided the kingdom so Svend got Scania, Knud got Zealand and Fyn, and Valdemar got Jutland. But at celebrations to mark the treaty, Svend arranged for both men to be killed.

Valdemar escaped and married Sofia to legitimise his claim to Zealand and Fyn. He then defeated Svend in a battle in which his rival died to become the king of all Denmark.

Nevertheless, like Ingeborg before her, Sofia is not mentioned much by the historians. Saxon Grammaticus and Arnold from Lübeck, the author of The Slavic Cronicle’, both only mention her twice: in connection with her marriage and in connection with her husband’s death in 1182.

She was kept busy though. Together with Valdemar, over a marriage that lasted for 25 years, she had at least seven children and instilled in them a sense of family that saw the siblings support each other through difficult periods of their lives – a family trait that was unusual for those times.

Sofia went on to outlive her husband by 16 years. She died in 1198 and was buried at St Bendt’s Church in Ringsted alongside her husband.

Princess Dagmar of Denmark

Following a number of unsuccessful attempts to arrange marriages between the Russian and Danish courts during the reign of the first tzar of the house of Romanov, Mikhail I (1613-1645) – religion proved to be a stumbling block as the Danish princes in question were not prepared to convert to Russian Orthodox – the two countries would have to wait nearly seven centuries for another Russian-Danish union, and this time the bride was Danish, not Russian.

Initially, Princess Marie Sophie Frederikke Dagmar, a daughter of King Christian IX (nicknamed the ‘Father-in-law of Europe’ because his offspring married into several royal houses) became engaged to Grand Duke Nickolai, the eldest son of Emperor Alexander II, after meeting him in Copenhagen in 1864. But Nickolai died of tubercular meningitis a year later in Nice, leaving the door open for the new heir to the throne, Alexander. Indeed Dagmar met him at the bedside of her dying fiancée.

It had been the emperor’s express wish for one of his sons to marry a daughter of King Christian IX, whom he personally knew and respected. Dagmar duly arrived in Russia in 1866, was baptised in the Orthodox faith, adopted the Russian name of Maria Fiodorovna and married. The couple then named their first son Nickolai in honour of their departed brother and fiancée.

A lot had changed in 700 years, both in terms of historical documentation and queenly duties, although Dagmar, of course, was an empress not a queen. And she went on to play a significant role in the development of Danish-Russian cultural relationship in general. In particular, she arranged orders for portraits of the Russian emperor’s family by the famous Danish painter Laurits Tuxen and helped Danish businessmen to establish useful contacts and obtain important concessions in Russia.

She devoted much of her time and efforts to charity. She was the head of the Empress Maria Institute, supervising charitable institutions in all the major cities of the Russian Empire, including 17 in St Petersburg and 10 in Moscow.

But these were turbulent times, and Dagmar suffered her fair share of loss. Her second son, Alexander, died at the age of one, and her favourite son, George, died of tuberculosis at the age of 28. She also lost her husband early – Alexander III died in 1894 – and the Russian Revolution of 1917 accounted for the rest of her Russian family: her sons Mikhail and Emperor Nickolai II, who was executed together with his wife and children.

Returning to Denmark, she chose to lead a quiet life at a summer home in Hvidøre, the same location where years earlier the families of several royal families would congregate for holidays. Her sister Alexandra had become the queen of Britain after marrying Edward VII and they remained close until her death in 1928 at the age of 81. In total, she spent 52 of those years in Russia and became very Russian in her ways.

Still remembered today

As time flies, governors come and go, and countries change their borders and names, their common historical past lends special value to the relationship between Russia and Denmark.

A unique exhibition, ‘Denmark and the Russian Empire in 1600-1900’, ran at the Danish Museum of National History in Frederiksborg from August to December in co-operation with the Russian state museums in Tsarskoye Selo and Pavlovsk (both places were Russian imperial residences). It provided some good examples of the strong cultural ties between the countries, which over the years have been inspired by remarkable personalities, both Russian and Danish.

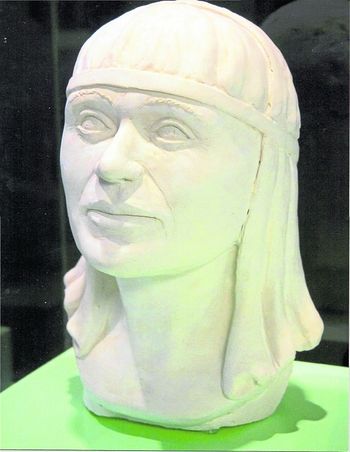

And just recently in September, a bust of Dagmar was unveiled in the square named after her in Frederiksberg.