In the Church, bread is a symbol of Christ. He Himself spoke of this: I am the Bread of life (Jn. 6:48). If earthly bread nourishes human life, then Christ, the Heavenly Bread, brings human life into communion with the fullness of divine life in eternity.

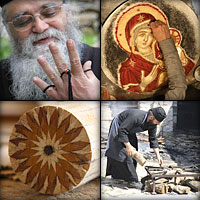

Prosphora is an inseparable part of liturgical life in the Church, and therefore the obedience of prosphora baker has special significance. Beyond the seeming simplicity of this God-pleasing work hides a multitude of subtleties, mysteries, and hidden activity. As long-time resident of the Moscow Sretensky Monastery, Igumen Cyprian (Parts), tells us about this.

We will learn why the Lord created wheat, why prosphora can be baked anywhere on Earth, and why the obedience of prosphora baker, which Fr. Cyprian has been performing for more than ten years now, is considered so important in a monastery.

Proskimedia. Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Anatoly Goryanov

Proskimedia. Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Anatoly Goryanov —Batiushka, why is the obedience of prosphora baker considered one of the most important?

—As we know, there can be no Liturgical life without prosphora. And the Church cannot live without the Liturgy. This means that the second building after the church is the prosphora bakery, where bread is specially cooked for the Liturgy.

—Who can and should bake prosphora? How has it always been done in Russia?

—In monasteries, of course, the monks or nuns have always baked the prosphora. But in parish churches, prosphora has always been baked either by pious widows or virgins, unmarried girls. They were called “prosphirny”, or, prosphora ladies.

This comes from the reverential attitude we have towards prosphora. Also out of reverence, the bakers would add holy water to the prosphora dough—this is not essential or required, but was done out of reverence.

Igumen Cyprian on his obedience. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov)

Igumen Cyprian on his obedience. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov) If a “white” (married) priest serves in a rural parish and his matushka (wife) knows how to bake prosphora, then of course she will do so—who else is there to do it? And this is normal. We have to take real live circumstances into consideration.

Now, in the monasteries, the monks and nuns themselves do the baking, both for themselves and for sale (to parishes). Parish churches either bake it themselves, or as it happens more often, buy it.

In ancient times, everyone could bake prosphora—it was an offering to the church. The best were chosen for serving the Liturgy. Just about every housewife knew how to bake bread, because this was part of her routine, and as they were all religious people and knew the requirements (that it should be leavened bread, using salt, water, and flour), any of them could bake prosphora at home and bring it to the church.

In Greece today, prosphora can be purchased in a store and brought to the church as an offering.

The brothers of Sretensky Monastery in the Holy Dormition Pochaev Lavra, July 2013. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov)

The brothers of Sretensky Monastery in the Holy Dormition Pochaev Lavra, July 2013. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov) —What needs to be done in order to always have a reverential, prayerful attitude towards prosphora baking, so that it would not turn into merely a craft?

—It always continues to be reverential. I have never noticed the reverence to cease. Not in parishes, nor in monasteries, where I have had the opportunity to visit the prosphora bakeries, nor in private prosphora bakeries have I ever seen it degrade into a mere craft. I don’t think that there is any danger here. I have never observed that happening.

—I have read that prosphora baking is called an ecclesiastical art. How did you learn to bake prosphora?

—Earlier, our monastery did not have a special prosphora bakery, and I was responsible for providing prosphora to the church because I was in charge of the vestry. One “fine day”, due to my own oversight, there were no small prosphora for the parishioners for the next morning. There were service1 prosphora, but we hadn’t stored or purchased any for the people. This was discovered on Friday, and we needed the prosphora on Saturday morning, but we could only pick them up on Saturday afternoon.

We found some imported American flour—terrible bleached flour—some French yeast, and we baked with this our first prosphora in the kitchen oven, where cookies had just been baked. As I now understand it, the prosphora turned out awful, they smelled like cookies, but at least they were there and the people were happy.

This got us going, and we decided to try baking prosphora ourselves. At the time, Hierodeacon Cleopa was under me in obedience, and we began baking in the kitchen at night. Of course, we were able keep this up for about a month before we collapsed—we weren’t sleeping at night. Maybe not every night, but we were tired just the same. However, we did begin to have our own prosphora. Then we started asking our Father Superior to start our own prosphora bakery. He gave the blessing, and after remodeling a new monastery building we equipped it. This was in the year 2000.

—You just mentioned the terrible American flour and the French yeast… Others might have thought that this was, to the contrary, a great thing. What kind of flour and yeast should there be?

—Why do I malign the American flour? Although not all American flour is bleached, it most often is. This is done solely for the color. They essentially ruin the flour.

French instant yeast is not very suitable for prosphora baking. It immediately produces a lot of carbon dioxide; that is, it rises quickly, which doesn't work for a large batch of prosphora—you can’t keep up with it, it simply “runs away”. Therefore we try to buy our own Russian yeast.

Dried yeast keeps longer, while fresh yeast keeps no longer than a month, after which its rising strength wanes… You can also use a sour dough starter.

At one point there was a buzz about only using natural sour dough. People would say, “They used to bake only with sour dough, but now they’ve gone to yeast…” However, they said this out of ignorance. In fact, the same yeast is at work in sour dough, only it is wild. Lactose bacteria and yeast of various kinds are practically everywhere. If you simply pour water over flour, then leave it in a warm place under the right conditions, the yeast will begin to multiply: that is your leavening.

Freshly baked prosphora. Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov)

Freshly baked prosphora. Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov) After some time, people learned how to grow yeast in large quantities in factories. Then, by selection they cultivated yeast that releases more carbon dioxide, and are more resistant to temperature changes.

What is yeast? It is unicellular fungi that can be subjected to selection, choosing the more stable forms that can easily ferment the sugar contained in flour—and that is about it.

Furthermore, sour dough leavening used to be called yeast. There was no difference. If you take the old book by Elena Molokhovets, A Gift to Young Housewives,2 and look at the chapter on bread, you can see that she always uses the word “yeast”.

But we understand it to be sour dough. People stopped using sour dough in bread baking because it is more capricious. If you want to bake prosphora using sour dough you can. But you need to renew the starter dough more often, so that the prosphora don’t become too sour tasting.

On Mt. Athos they use sough dough—at least they do in Vatopedi, and in a number of other monasteries—and they bake as they always have. They renew the starter, that is, they make fresh starter, twice a year, on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, for example, and in the third week of Great Lent, the Veneration of the Cross, or on Great Saturday—I don’t remember exactly, but anyone can find out who wants to. They call this leavening miraculous, but that does not mean that it rises without yeast. There is yeast in it.

The fact is that it ripens quickly—literally during the services. This is what the grace of God consists in here—that it happens very fast.

But this happens in any place. There is no inhabited place on Earth—well, perhaps besides some northern islands—where nothing ever spoils, where there is no yeast or lactose bacteria. The Lord has made it so that prosphora can be baked everywhere.

And there is another amazing fact: we serve the proskemedia on wheat bread, but only wheat has unique bread baking properties. No other grain has the same qualities. The Lord created wheat so that we could bake the best leavened bread, which can be used to serve the Liturgy.

—Batiushka, why do Greeks serve using only one prosphora, but the Russians use five?

—It’s basically a matter of tradition, and it is a tradition that is not dogma. Whether you serve the Liturgy using one prosphoron, two (as they often have on Mt. Athos), five, or seven, there is no essential difference. You can serve on one prosphoron. Well, maybe you only have one: what else can you do? You can serve the Liturgy. Why not? In that case you need to cut out the center as the Greeks do—the Lamb—and the other parts are used for the components: the Mother of God, the nine ranks of saints, for the health (of the faithful), and for the reposed… On the stamp the Greeks use, if you have seen it, all five of our stamps can be seen: in the center is the Lamb, to the right is Mother of God, to the left, the nine ranks of saints.

This is a matter of local tradition. We must have unity in things that really matter, while variation is allowed in all the rest. This is just one of those allowed variations. Some Old Believers came to Mt. Athos in the late 19th century in order find out who in fact is in error—them, or the “Nikonites”. Mt. Athos truly was the guardian of Church tradition and rites. They asked the father confessor of the St. Panteleimon Monastery Hieroschemamonk Ieronym—I can’t recall his last name. He was a well-known ascetic. He answered them, “As we served in ancient times on Mt. Athos, so do we serve now.” They served on two prosphora: one was the Lamb, the second was all the rest. And his explanation for this was quite simple: it was out of poverty.

If they needed to serve in one of the kellion, in order to use less flour, the desert dwellers out of their poverty allowed the monks to serve using two prosphora, and there is no catastrophe in this. This is an ordinary, normal thing. There was a time in Russia when they served using seven prosphora. And there was no catastrophe in that, either. And how many prosphora are prepared if a bishop is serving? Seven—the usual five plus two for the bishop. Also seven. This is a matter of practice, and there is no need to make it a strict rule.

—If we return to that night when you and Aunty Liuba baked prosphora for the first time… Did you receive your further knowledge through experience, or did you study somewhere? Do they even teach this anywhere?

—We baked the small prosphora, but it took a long time to get the large, service ones right. We bought them in Danilov Monastery. Well, one Sunday, Father Superior came to the services, as usual, and asked, “Fr. Cyprian, whose service prosphora do we use?” “Batiushka, they are from Danilov.” “Why Danilov?” We have our own prosphora bakery.” “Batiushka, we don’t know how to do it, we have to learn…” He said, “Well, that’s it. We will not buy prosphora; we will bake them ourselves.”

I started counting in my mind how many Danilov prosphora we had left, and I figured that there aren’t enough for the weekdays, and there are no Lamb prosphora for next Sunday. What else was there to do? Where could we learn? I asked a nun I knew who bakes prosphora. I called her at the Convent of the Conception—Matushka Sergia, a remarkable nun, now reposed. I asked her, “Matushka, can I learn how to bake prosphora from you?” She said, “Maybe it would be better for you to go to Fr. Adrian at Novo-Spassky (Monastery)? I said, “Matushka, can I learn from you?” “Well, you can, come on over.” “When do you bake?” “Thursday.”

I worked the whole day with them. Of course, I had some experience, but there I saw my major mistakes; they taught me how to roll the lower tier of the prosphora, to make little balls…

And here was another monkey wrench: I worked all day with them baking, and they bake for sale, but I can’t tell Mother Sergia, “Sell them to me,” because Father Superior forbade me to buy prosphora, and I couldn’t bring myself to say, “Give them to me.” She probably would have given them to me, but I didn’t ask…

I had only Friday evening left. Well, glory be to God, I saw my major mistakes, corrected my dough, and what do you think? On the very first evening, there were absolutely normal prosphora. It was God’s mercy!

Igumen Cyprian at his obedience. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov)

Igumen Cyprian at his obedience. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov) Of course I prayed, and asked Great Martyr Barbara, because it was the eve of her commemoration. And the prosphora turned out fine! Sunday, at the Liturgy, Father Superior sees the prosphora and they are normal service prosphora… “Fr. Cyprian, whose prosphora are these?” “Ours, Batiushka.” “What happened to you?” “Batiushka, it’s God’s mercy.”

You see? If Father Superior had not said, “That’s it, we’re baking them ourselves,” how long would I have stuck with only the small ones?

It’s better to learn from other prosphora bakers, to work right in the bakery, so that they could show you then and there how to bake, because you can’t write down everything. I can’t imagine being able to show you how to roll the lower tiers correctly if you don’t see it for yourself, if your hands don’t touch the dough.

In order to learn how to bake prosphora you need to bake alongside a good prosphora baker, and even visit other bakeries. It’s very important to share experience.

Freshly baked prosphora. Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov)

Freshly baked prosphora. Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov) —What is the prosphora bakery in Sretensky Monastery like today?

—It is like a small bread bakery. Nothing special. An oven, a dough mixer, a roller through which the dough is worked to give it a uniform, firm structure. Tables for cutting, and cabinets where they rise before baking.

—And who bakes them? Monks, novices, or someone you’ve hired?

—We have no hired workers for this; I bake the service prosphora myself, because there is not so much dough, and I can manage without any help. The machines make that possible. But the small prosphora… The seminary students have their obedience in the prosphora bakery—they help with the cutting, because we have to form around three thousand prosphora in two and a half hours.

—How often do you bake?

—When needed. This depends upon the feasts: the more feast days, the more we have to bake. But we bake service prosphora three times in two weeks.

—Do the students like this obedience?

—We’ve had so many seminarian helpers, you know, the question doesn’t come up: “Do you like this obedience?” They work diligently, and try to do their best. I am grateful to the guys for their help and their diligence, because they have to do this obedience in the evenings after dinner, when they have spare time, which means that this is an extra load for them. But they manage, and labor. They might do this obedience for years, until they graduate. That means that they want to do it. Understand, that baking prosphora is something that the person has to like. People are of varying temperaments—some paint icons, others do carpentry. That is what they like. One has to relate to this work of baking prosphora in the same way. Otherwise, the prosphora won’t turn out well. Do you get it? We are working here with something that is alive: yeast is made of living organisms. That’s the thing. A person has to like this work in order to be successful in it.

—That is, it can’t be done mechanically?

—No, it can’t be done mechanically. I didn’t understand this until I started baking. I related to prosphora in a totally different way. First of all, I did not know what kind of work this was. Secondly, I did not understand how to approach it at all. What could be so hard about baking prosphora? I came with this attitude to one remarkable prosphora baker, Fr. Adrian at Novo-Spassky Monastery. I asked him, “Give me your recipe.” But he answered, “Do you know what gluten is? Do you know what GDM (gluten deformation measure) is? These are characteristic of flour. I thought, “Why is he saying this? All I need is a recipe!”

On Mount Tabor. A pilgrimage to the Holy Land, 2005. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov)

On Mount Tabor. A pilgrimage to the Holy Land, 2005. Photo: Hieromonk Ignaty (Shestakov) Later, when I started baking myself, I understood that you have to know this, and that he didn’t say these things in vain; because if you don’t take them into consideration you can’t successfully bake prosphora. You either need enormous experience in the tradition, or you simply need to understand what processes are happening.

Incidentally, what really helped me in baking prosphora, in understanding the baking process (prosphora is after all essentially bread, only it’s special bread) were books on bread baking—ordinary books that you can find anywhere. They give you an understanding of what is going on, and that is not superfluous. Moreover, these books helped us in another way—we also bake bread in the prosphora bakery for the brothers. In general, the main thing in baking prosphora is continuity. The second thing is your own experience, which is indispensible. Books on bread baking are helpful as textbooks.

Translation by OrthoChristian.com

1 At the proskemedia, five service prosphora are used. From the first is cut the Lamb, which later becomes the Body of Christ. From the other four prosphora the priest removes a particle in memory of the Theotokos, the saints, which include those who composed the text of the Liturgy, and for the commemoration of members of the Church both living and dead.

2 Elena Ivanovna Molokhovetz (1831–1918) wrote the classic of Russian culinary literature, A Gift to Young Housewives, or the Way to decrease expenses in housekeeping (1861).

Otherwise this was a lovely article about baking phosphora.