Twentieth-century readers knew Kerouac’s On the Road and Jack London’s earlier hobo classic, The Road, but how many of us know what the 21st-century counter-culture is up to, their life-styles and aspirations? We see the tattoos, nose-rings, attitudes, but do we hear the cries of the heart from young people searching for truth? In the following interview Rainbow (Xenia) Lundeen and Seth (John) Haskins, both baptized Orthodox after this conversation, share the by-ways they’ve taken in trying to live out the Gospel in their lives.

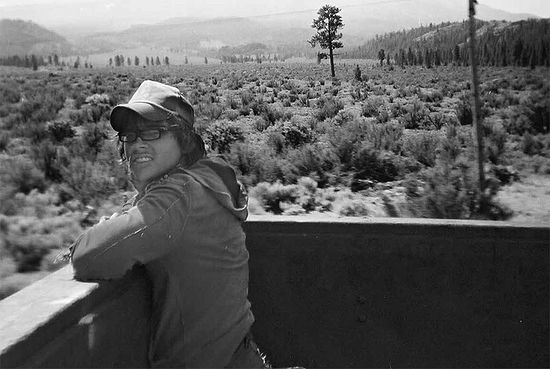

: Baptism of Rainbow (Xenia) Lundeen by Fr. Paisius Altschul at St. Mary of Egypt Serbian Orthodox Church, Kansas City, Missouri.

: Baptism of Rainbow (Xenia) Lundeen by Fr. Paisius Altschul at St. Mary of Egypt Serbian Orthodox Church, Kansas City, Missouri. RAINBOW: When I was very young, my parents were dedicated Seventh Day Adventists, but after bad experiences with the church they left Christianity, and my brother and I were raised pretty much as agnostics. When I was twelve, I had some Christian classmates who tried to convince me that Christ was God, but it seemed so superficial that when they said things like, “Jesus loves you,” I put my fingers in my ears. Not long after, though, while listening to Christmas music alone in my room, I suddenly experienced not just a heavenly feeling, but the presence of Someone who I knew was Jesus Christ Himself. I accepted Christianity then, but it wasn’t until ninth grade when I began hanging out with Christian friends that it became part of my life. Galatians says, “If we live in the Spirit then we should walk in the Spirit,” and it struck me that Christianity wasn’t just a list of rules of things I shouldn’t do. If I believed in God, I should follow Him. In high school I’d gotten into punk rock culture, and at seventeen I moved to Washington to study commercial photography at the Art Institute of Seattle. After a few semesters I was tired of hearing how to make money with my art. I didn’t want to sell myself or my photography. I was sick of society, of the pursuit of money, of rent, of meaningless jobs, and of my own vanity, but I didn’t know what I was looking for.

Then I made a new friend, Learning, who’d just gotten back from his first train-riding trip. It was perfect timing. Learning began to tell me about owning nothing, about riding freight trains and sleeping in forests, bushes, and alleyways, and all of a sudden I thought, “I’m ready for that.” I was all set to leave with a Bible and a backpack, but it was already late fall, a bad time to start travelling. So I stayed in school, but now I had friends who thought as I did and we began to live together and play music.

RTE: What kind of music did you play?

RAINBOW: We called it Anarcho-Folk. I wasn’t really much of a musician— I played a little auto-harp, guitar, tambourine, harmonica… wherever I could fit in. I’m not very good at anything.

SETH: She plays a mean trumpet.

RAINBOW: Mean to the ears. Music was a way of feeling free. I also started sewing, and even my photography began taking a more creative turn. I was trying to live these things, not just use them, and life took on a different light. Our band was called Compost, and the next summer we went on a twomonth tour around the U.S. with fourteen of us in two vans, camping out as much as we could. We also played at Cornerstone, a Protestant music festival that’s been put on by Jesus People, USA, for almost thirty years. Cornerstone is one of the main gatherings for Christian travelers, especially at “Hobo Jungle” where folks camp out. There are a lot of young travelers in the country, 18-25 years-old, but only a small number are Christian, so most of us know each other and we try to stay connected.

That year we also started something that we jokingly called “Christian Summer Camp.” It was a bunch of Christian punks who decided to go on a campout, but it ended up becoming a country-wide gathering as people brought their traveling friends.

After the tour a friend and I started hitchhiking and we did the whole country: Chicago, Michigan, New York, Philadelphia, Kansas City. Our final destination was Oklahoma, but the further south you go, the less likely people are to pick you up, even a couple of harmless-looking girls. Finally, one trucker said, “I’d take you, but I’m going to California.” We said, “We’ll go,” and so we ended up in Southern California, and made our way back up the coast.

I soon took off again with my friends Learning and Jacob and we started riding freight trains as our main means of transport.

RTE: How did you manage that? Aren’t there still train guards, like in old movies, who watch for hobos?

RAINBOW: There are still train-cops and they’re still called bulls, like in the old days. Pretty much all yards have bulls, but you know what cars they drive and you avoid the watch-towers. You stay in the dark or the trees and once you’ve spotted your train, you go for it. We would pretty much always get on the trains while they were stopped in a train yard, or during a crew change. Other riders might jump on once they’ve started.

RTE: Did you take food?

RAINBOW: Yes… a can of beans or a can of tuna, an apple. Most of the time you weren’t on a train for more than twelve hours. The longest I was on was 24 hours, and that was longer than we’d expected, so we didn’t have food with us. But realistically, a day without food isn’t a big deal.

RTE: Especially once you’re Orthodox. Seth, what about you, what’s your story?

SETH: I was born and raised in Mustang, Oklahoma. My family is from southeastern Oklahoma; my grandfather was the vice-president of the Oklahoma Baptist Convention, so I grew up in the church. My dad is a cop and when I was about nine years old, my folks split up. My mom, older brother and sister and I lived pretty poor on a dirt road outside of town in the middle of nowhere. Some of our neighbors lived in trailers, others had houses; one family had a herd of buffalo and horses and cattle. We had a lot of room to roam and I grew up loving nature and animals. As a teenager I started hanging out with skateboarders, the kids about whom everyone said, “They’ll all be in prison in fifteen years.” (None of them are yet).

Yet, I was a believer and continued to play in the worship band at church because the spiritual side of things was always on my mind. I’d started making some bad decisions until one day I heard about fasting and decided to try it. I began to fast, pray, and read my Bible, and something clicked—things started making sense. From that point on, I tried to live what I knew about Christianity in a real way. The Baptists I grew up with are moral people, but often pretty rational. Church centers around discussion and debates about belief, whereas I was looking for something that I could use in life.

I was still active in church, but I could feel myself growing apart and folks thought I was losing it. Baptists have a very clear idea of how one should live—the need to make money was emphasized as was “how everyone does things.” Homelessness and a lack of money were bad. You could help people out, but the attitude towards someone in need was, “Pitiful you…”—the stray-cat mentality of “Don’t make eye-contact or they’ll want you to take them home.”

At some point in high school I began looking at poverty with romanticized affection. I wore ripped up flannel shirts, jeans, and an old trucker hat that had belonged to my grandpa. I was happy to be at the bottom of the barrel and to be alright with it. In spite of that everyone still liked me at school, though they were on a different track.

Around this time I also rediscovered the spiritual aspects of my Native American ancestry and met a medicine man who taught me some spiritual principles that I tried out on my own. It seemed a long way from my Protestant background, but later when I discovered that Orthodoxy also had a tradition of healing the soul, it all synced up. Orthodoxy was the fulfillment.

After high school, I played spaghetti western music in a band in Oklahoma City and worked at UPS. My first real crisis was over an old Mexican-American guy named Danny who’d been hitchhiking from southern Texas to a job in the north. On his way through Oklahoma, he was attacked and had a huge axe gash in his leg. He was discovered by a highway patrolman, who gave him $10 and found a trucker to give him a ride into Oklahoma City. The trucker took him to the Mercy Hospital emergency room where they gave him some painkillers, took him in an ambulance to downtown Oklahoma City, put him out and told him not to come back. When we found him, his leg was already turning black. He was in terrible pain and we took him to the state hospital where they told us that we couldn’t stay with him. The hospital wouldn’t ever tell us what had happened to him, and I don’t know if he lived or died. That was when I really began thinking about how I wanted to live, and soon after, my friend Darren and I moved to the Commonwealth in Bartletsville, Oklahoma, an unofficial community of kids thinking about the same things we were. Commonwealth was where I met Rainbow, and where I first met the traveling kids.

Most of the travelers I know came from the punk scene. I’m not punk at all. Each to his own, but it’s not my thing, and I’m not worried about impressing a competitive crowd. I was just a hick from the sticks, but I was interested. After my experience with Danny, I understood that I had to make a choice: to ignore what I’d seen and get on with a comfortable life, or to consciously join the other side and take it with everyone else who was poor. I figured I’d rather take the insults and everything else that was heaped on the homeless than turn my back.

As it turned out, I didn’t learn much from the Commonwealth Community, but one important thing did happen there: our friend Rachel took us to Holy Apostles Church in Tulsa, my first experience of an Orthodox church. The parishioners were nice and didn’t care that we weren’t well-dressed. You could tell, too, that they were family. Later at a Greek festival I met a welleducated monk from Constantinople named Fr. Victor. He talked to me for a long time about church history, languages, everything. It was all new to me and I was blown away. I thought, “This guy knows more about what I think and about the Protestant church than I do.” When I told him, “I don’t have a denomination, I’m just a Christian,” he asked, “So, what do you think?” He made it clear that even our ideas about what the Bible means have to come from somewhere, and you want it to be the right place.

The most amazing thing about meeting Fr. Victor was that when he began talking about the apostolic lineage I realized that there was not only wisdom here, but real authority that wasn’t just made up as you went along. This was something I’d never seen before, and later I saw it in other Orthodox people. They aren’t trying to convince themselves with scripture as they convince you. They’re just in it. From that moment, I wanted to learn more about Orthodoxy.

Another friend I’d made at Commonwealth, Michael Perkins, had already been Orthodox for a few years. He’d read quite a bit and said, “I’ll try to answer your questions, but I don’t know a whole lot. What I do know, I’ll tell you.” I was surprised because he wasn’t using the pious tone that I was used to, that I’d acquired myself because it seemed to be the right way to talk about God. Michael was just open. I was also impressed because neither he nor Rachel put a spin on Orthodox things to make them seem better than they were. They were real and down to earth.

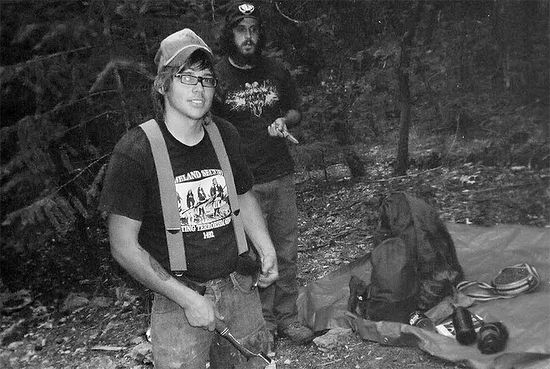

At the end of ‘07, my friend Christian and I left Oklahoma to travel: Chicago, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Charlotte, Nashville …. Our first train trip was in the middle of January in a thunderstorm that followed us for sixteen hours. We were in empty freight container cars, which don’t have a floor or a roof, just an open frame with a space along the edge that you can sit on. You sit holding onto air hoses in the wall, but you can’t fall asleep or you’ll fall off. Most of what should be the floor is completely open to the tracks.

RAINBOW: (smiling) Most people don’t actually ride in those.

SETH: We were in a hurry; later we’d know better. So we were sitting on the train on a cold metal ledge in a thunderstorm with wind and lightning all around us. My poncho had gotten sucked under the train when I’d tried to put it on, so I was soaked to the skin. In the middle of the night when the train stopped, we got off to look for a car that had a floor, but couldn’t find one and ended up in the same car crouched over so that we wouldn’t be seen for the last two or three hours after dawn. That was my first train ride and although it was so hard, the idea of being free was great. Nothing else seemed to matter. On the road, you’re free to think as you like. Being poor and Orthodox, you aren’t tied down to money or possessions, or even to false ideas about yourself that you have to preserve. I had begun to admit I wasn’t the greatest guy, because with Orthodoxy I was free to do something about it. You really do want to be holy, you want to be right, to be close to God, and it’s a relief to realize that you’re just lying to yourself and to other people if you pretend you’re already there.

RTE: How many young Christian travelers are there and how do you keep in touch?

RAINBOW: About fifty to a hundred that are well-connected to our community. A lot of people stay in contact through the computer, although I don’t use computers. We’re all pretty close, so if you talk to one or two of your friends, you find out what everyone is doing.

SETH: There’s an even bigger community of Christians who used to travel, or who want to travel and haven’t been able to yet, or people who are simply friends with travelers. When you go to their town, you know you can stay with them. Once you start traveling, you learn to spot other travelers immediately, even in a big city. They’ll have coveralls or patched-up clothes with neutral colors of green and brown. You’re already friends at the first meeting; you share your squat, your food, and help each other out any way you can. There’s a camaraderie here that you don’t have with most people, which was something I began to find with some Orthodox folks as well. You can’t fake that and you can’t buy it. I have to say though, that I’ve pretty much stopped traveling with the Protestant Christian travelers, because they tend to have a mistaken, negative view of Orthodoxy.

RTE: When you talk about travelers are you talking about folks who don’t fit into society, and so travel like Depression-era hobos, or are these mostly young people who have adopted values similar to your own?

RAINBOW: Mostly they’re intentional travelers, young people who choose to be homeless and to travel—usually by train-riding and hitch-hiking, squatting in towns, camping in the forest. Of course, there are the other kinds of travelers too, and sometimes the lines cross.

RTE: Do you feel an affinity with the Depression-era travelers like Woody Guthrie?

SETH: Yes. Not to say that Woody Guthrie and others like him were Orthodox, but there were many things they wrote and sang that Orthodox would agree with. He once wrote a song that if Christ was to come back, we would probably treat Him like the Jews did. The world hasn’t changed much, and I agree with that.

RTE: You are both musicians. What songs inspired you along the way? seth: For me it’s Woody Guthrie’s “Jesus Christ” and “Hard Traveling” And another, called “Waiting for a Train” by Jimmie Rodgers. rainbow: “Little Boxes” by Malvina Reynolds. It was a good reminder of what we were leaving behind. And “Blackbird” by the Beatles… “Take your broken wings and learn to fly...”

Most of us feel that traveling is one of the few truly American heritages. There are similarities with gypsies, pilgrims and so on, but the hobo culture with trains and hitching is uniquely ours. Most travelers hate mainstream capitalism, greed, unjust wars, suburban life—the little boxes on the hill-side—but traveling is something we can embrace and we’re happy there are American things we can embrace.

RTE: America is one of the only countries large enough to have long-distance trains and enough space to be able to travel extensively. Weather usually isn’t too extreme, and today’s culture is accepting enough that you won’t starve. It’s also a freer time for women. It would have been much harder a century ago.

RAINBOW: That’s true, although around the turn of the century, my greatgrandfather’s second wife traveled with the hobos before she married. For me, a lot of the draw of traveling is the history. I’ve always felt I was born too late and the eras in which I feel most comfortable are increasingly distant. In high school I thought that I should have been born in the ‘60’s; later I started wearing ‘40’s and ‘50’s clothes, and once I started reading classic literature, I felt sure that I belonged to the 19th century. Going forward didn’t seem to be getting us anywhere. Of course, my dreams were romantic, but the thrust was that I was going backwards, I was going old-fashioned.

RTE: Was your train riding as uncomfortable as Seth’s?

SETH: Her experience wasn’t uncomfortable, it was tragic.

RTE: Do you want to tell us about it?

RAINBOW: In the winter of 2007 I spent a month in Tucson, working at the big international Gem and Mineral Show. A lot of travelers stay there for the winter, because the climate is good and the show hires temporary labor. I needed to work because I had school loans to pay off.

RTE: You were working to pay your debts?

RAINBOW: Yes, I knew that the loans were my responsibility. I’d worked at the show selling fossils for Moroccans, and squatted with other travelers. Learning was there too, and after the show we decided to head to L.A. on a hotshot— a fast, high-priority train that has fewer stops. On the way we wanted to get off early to meet some friends near Niland, California. We were watching the road for traffic to see if we could hitchhike back from the next stop, but there weren’t any cars at all. We were thinking, “Oh man, hitch-hiking’s going to be so bad. We’ll end up walking thirty miles.” But when we saw the sign that said Niland, the train started slowing down. We got excited thinking it might stop, but when it got down to walking speed, it started speeding up. We thought, “Oh no, we’d better go now while we can,” but we took too long to get ready. Because I had a mandolin and a dog, I couldn’t just jump and roll. I had to climb down the ladder, jump off running and grab the dog from the door. I knew the train was going too fast, but I’d only ridden about a dozen times, and I didn’t yet know that if you get off with your trailing foot, the one behind you, you spin out away from the train. If you put down your leading foot, you spin towards the train. It’s natural momentum.

So, the train was going too fast and I got off with the leading foot and was instantly on the ground. As I was going down, I thought, “This is how people die on trains, this is how it happens.” It happened too fast to be scared, but I also knew it was too late. I didn’t die, of course, but I’d broken my back and my pelvis. Learning saw me go down and jumped off behind me with the dog and the mandolin. He helped take my pack off, then picked me up and tried to help me to the road. I couldn’t walk all the way, so he ran into town and got an ambulance. I had surgery, of course, and now I have a whopping hospital bill.

So riding trains is largely over-romanticized and I want to make sure that our lifestyle doesn’t come across like that in this article. It is a wonderfully freeing way to live, but it’s a dangerous way to live. It’s not for everyone and it’s not just a cool thing to do. Riding trains can be a status thing for some people. They think, “I’m cool because I ride trains, but you only hitch-hike. You’re not a real traveler.” I once met a kid who boasted of having ridden fifty trains in the past month. That’s like twice a day of doing nothing but riding trains for the sake of riding trains. For us it was a way to get somewhere. seth: If anyone reading this wants to be free, we’re telling them right now that they don’t have to go out and ride trains. In fact, if they feel drawn to it, I’d say “Don’t.” That’s not how it works. It’s too dangerous.

RAINBOW: The traveler community was amazing though. I was in the hospital for nine days (the first four waiting for surgery) and thirteen travelers came from five different states when they heard I’d been hurt, to see what they could do. They read to me and took me outside as soon as I was allowed.

RTE: How long before you could walk?

RAINBOW: I walked ten feet the day after surgery, and was out of the hospital three days later.

RTE: Have you jumped a train since?

RAINBOW: I didn’t for almost three years. Mostly because my focus had changed to learning about Orthodoxy and paying off my debt. At first my pride told me that I had to ride again to prove that I hadn’t been conquered by fear, but I had to accept that it was alright if I didn’t ride trains anymore; I had to let my heart and motives shift. By the time I did start riding trains again I wasn’t afraid, I wasn’t trying to prove anything. I was just riding the rails with good friends, trying to get around.

RTE: Rainbow, when did you start feeling a mesh between Orthodoxy and your personal values of voluntary poverty, of helping others out?

RAINBOW: Mine was definitely a process. After I’d broken my back and begun traveling again, it was spiritually a really uncomfortable time for me. I felt as if I was losing my grasp on everything I’d believed in. I’d been to so many churches and seen so many Christians, all of whom believed something different. I thought, “If everyone’s just making this up for themselves, then I don’t really care to follow it. I don’t want something I make up for myself.”

So, I didn’t know what to do, or if I could even call myself a Christian. All I had was that deep desire to seek God. I was pretty sure I still believed in Jesus Christ, but I didn’t know where to go with it, and this was when I first went to Holy Apostles Orthodox Church in Tulsa. I was sure I’d hate it because I was an anarchist, and this was hierarchy, structure, tradition, dogma… everything I looked down on. Later, I figured out that when these things are acted out in worldly forms they usually fail, but when it’s God’s hierarchy, it’s different. This was exactly the foundation to the faith that I’d been missing.

The first thing that struck me was the beauty and the reverence: “Of course we should be honoring God and not treating Him like He’s our ‘surfer bro’.” Some things were strange at first. I remember noticing in the liturgy that we kept saying, “Lord have mercy” and I wondered, “How many times have we said this?” but at the same time I thought, “What else do we have to say to God?” Then when I started reading about the saints, and that these people were being praised for their humility, meekness, for giving away their wealth, about the Fools for Christ, it all felt so right. I had often talked to traveler friends about how we wanted to spend our lives in lowliness. We had no idea how to do that, or even what it meant, but here the saints were showing the way. This was the ideal, and it fit in with my desire to be oldfashioned, to go backwards. It was so pure and simple.

RTE: How about you Seth?

SETH: For me, every first impression of the Orthodox Church was golden. I had just discovered Fr. Seraphim Rose’s book, God’s Revelation to the Human Heart, and everything he said made a lot of sense to me. It all began to mesh when I stayed with a Nashville friend in an old bus that had been transformed to run on vegetable oil. He’d rigged up a wood stove and we lived there through the winter, going to a Greek Orthodox mission dedicated to St. John Chrysostom.

Fr. Parthenios Turner and Presbytera Marion also run a bookstore and a coffee shop. When I first went in, I said, “Father, bless,” and told him that I wanted learn about Orthodoxy. He had me put my bag down, asked if I was hungry, and then said, “OK, here’s a rag and some soap. I need you to clean some tables and when you’re done, vacuum the floor.” I was kind of glad because I’d always just made my way doing what I wanted, but he immediately made me feel a part of things. I knew then that his strictness was good, and that I needed it. When I finished he said, “Seth, are you done?” “Yeah.” “Then please come here.” He took me to an icon of the Resurrection and said, “This is what we strive for,” and explained everything on it. Over the next few days, I’d come in, do some work, and little by little he did the same with all of the icons in the store.

One day he said, “While you’re doing the dishes, don’t just do the dishes. Pray.” I said, “OK,” and he said, “Not just any prayer, say the Jesus Prayer. Do you know it?” I said “Yes,” because I’d already realized that the way I’d been talking to God was too familiar, that there wasn’t a sense of God as God and that I’m his creature. So I started saying the Jesus prayer on the train and remembering my sins. I understood that this was prayer and life.

Earlier I’d read that St. Francis of Assisi had said: “Go dig a hole and pray at the same time, and then go dig another hole.” I may not be remembering it right, but it was the idea of work and prayer together that stuck with me, and that was what Fr. Parthenius taught us. He was like a father. We left town, though, very quickly when someone in my family died. I didn’t have a chance to say goodbye.

RTE: He’s a subscriber. He’ll read this.

SETH: Good. This was January of ‘08, and after going home for the funeral, I got a job on a ranch in southern Oklahoma. We were working ten-, twelve-, thirteen-hour days. We were cleaning out stalls, grooming the horses, and working rodeos with all of the manual labor that goes with it. We were also learning how to train horses. That was our life. We still felt free, but we were working with horses. I love animals and each of the horses had different personalities.

Some would nuzzle you, others would play with you by grabbing your hat and holding it up so you couldn’t get it. This was Lent and I spent my free time reading and praying. My friend Hanna (Rachel) had sent me a lot of books, and this was the first time I read The Way of a Pilgrim.

Around this time, I came to St. Mary of Egypt Serbian parish here in Kansas City. Rainbow [Xenia] was here and another friend, and this was my first meeting with Fr. Paisius Altschul, who has always made me feel like I belong. It gave me time to contemplate what I’d seen. Afterwards I went to Tulsa then and met Turbo Qualls, who has been like a godfather to me.

He’s in his thirties, comes from the same subculture, and is married with children. He really understands that the spiritual is attached to the physical, and after he explained this, liturgy became something really important to me because it lifts us up to heaven; we’re worshipping with angels.

The other thing that was really important to me at this time was the St. Herman of Alaska Monastery in Platina.

RTE: What was your experience of the monastery?

SETH: Except for Fr. Victor, the monk in Oklahoma, I hadn’t seen monasticism before and didn’t know what to expect. When we pulled up, the monks were all sitting at the gate. Abbot Gerasim wasn’t there yet, but Fr. Damascene was there and Fr. Gabriel, who I immediately felt comfortable with.

He’s got a big red beard and walked over with a walkman playing Greek chant and two dogs trailing him. I didn’t know what to do, but he just came over and said, “Hey, how are you doing?” It was so normal. I was thinking we’d sleep for two hours, then pray for ten, and not eat; and though we did pray a lot, it wasn’t quite like that. Abbot Gerasim is so kind and smart, and he and Fr. Damascene answered a lot of questions. They are two of the smartest people I’ve ever met, and they blew my mind.

RTE: Did you also get to St. Herman’s, Xenia?

RAINBOW: Yes, my heart is always in Platina. It has been a great source of instruction and inspiration to me. I also got to Alaska. When I decided I wanted to go to Alaska, to Spruce Island and to St. Nilus Island where the nuns live, I planned to hitch up the Al-Can Highway, but by the time I got to Seattle, I was tired of hitching, so I decided to try something new, and went to the fishermen’s terminal to ask if anyone would give me a ride to Alaska.

I found a charter boat that was going home empty, so I got all the way to Homer (in luxury) and then took the ferry to Kodiak. I loved St. Nilus Skete and the sisters. It was so extreme: no roads, incredible peace, and the services at 4:00 in the morning. Since I’ve met Orthodoxy, travelling is totally different. Now I’m a pilgrim, rather than a hobo.

RTE: It’s fitting that you hope to be baptized with the name of St. Xenia of Petersburg, the original homeless wanderer. Seth, has Orthodoxy also changed traveling for you?

SETH: After you travel for awhile, although it’s wonderful, you miss stability and community. When you travel, you need that stability, the inner discipline that I lacked. Without a sense of purpose, you travel with highs and lows. You think, “What am I doing?” Well, I’m traveling, and if I don’t travel, who am I? I’m nothing.” It’s a big adventure, it makes a great story, beautiful sunsets and landscapes make you peaceful, but when you have the teachings of the Church in your mind and feel yourself to be part of the cycle of the Church year, those deep services give a stability and community outside of yourself.

When I first got here to Kansas City I stayed with Rainbow, got a day job, and settled down to be a catechumen. At first the stability and the routine were frightening, but I’ve found over the months that the need to repent has come more clearly to me, and I’ve realized that whether I’m on a sweet, awesome, gnarly trip or I’m just hanging out here in the city, it’s all on the way to heaven.

There’s nothing more important to me now than serving God and being part of the Church. Coming from no bosses and living off the seat of your pants to a serious obedience is different. I want to trust the Church and Fr. Paisius helps me with that. I realize that if I’m going to be Orthodox, I have to be fully Orthodox, not lukewarm and taking part in the way the world operates. Orthodox translates into right belief and right practice, and I know I have to have both. I’ve settled down as a catechumen, but I don’t think I’ll ever leave the traveling culture. If it wasn’t for the travelers, I probably wouldn’t be Orthodox.

RTE: Hopefully, there are many parishes open to welcoming travelers. The first hermits retreated from the world for some of the same reasons you have, a protest against society and a longing to live for Christ, but they still needed help, even if it was just someone to buy their palm mats. They rarely lived in splendid isolation.

RAINBOW: I’ve been reading bits of St. Maximus the Confessor, and there’s one part I keep coming back to: “He who does not count equally as nothing honor and dishonor, riches and poverty, pleasure and affections, has not yet obtained perfect love. Perfect love counts as nothing not only these things, but temporal life and death.” So, it’s not the riches or poverty that makes someone good or bad.

Of course, we were also told by the Lord to give away our riches to the poor, to become lowly, but things in themselves aren’t good or bad. It’s just hard to have a lot and stay straight. Through traveling, I learned to trust the Lord’s provision like I couldn’t have in any other way. We made ourselves completely helpless. We had no idea of how we would eat the next day or if we would have somewhere dry to sleep that night, but we were always taken care of.

Even though we are against worldliness, there are lots of good people living in the midst of the world. One of the amazing things about traveling is everyone you meet. For example, a middle-class soccer Mom might pick you up on the road and feed you and take care of you—almost always it was lower- and middle-class folks. You saw the best of people and the worst of people. I never flew a sign asking for money, but I was never without it. Some police officers might treat you like trash, but there were others who would stop to be sure you weren’t runaways and then give you $10 and tell you to be safe. Also, among the travelers you saw the worst and the best. You saw kids who were just interested in drink, drugs, and sex, but others who were staying clean from all that because they were looking for something better.

For now, I’m living in Kansas City as part of St. Mary’s parish, holding a job in a tiny café and paying bills. I’m amply provided for, but because I’m the one punching the time-clock it’s more of a struggle to feel that these things are from God and to remember my dependence on Him. Anyhow now I have something to give; it all goes around.

RTE: You’ve reminded me of a great Thoreau quote on voluntary poverty, that “life near the bone is the sweetest”. What would you say to kids, especially in other countries, who have similar feelings but whose situations wouldn’t allow this lifestyle; they don’t have the luxury of just taking off or not working. A desire for spiritual freedom doesn’t always go hand in hand with physical freedom.

RAINBOW: First of all, it’s not for everyone to go traveling in the way we do. It isn’t safe, and it’s not a universal answer. But to keep the spirit of it, I’d say first, “Stop caring so much about how you look. You can stay clean, but stop caring about make-up, about nice clothes, about having money and being comfortable and cool.” Then, I’d say, “Start giving away as much as you can. Try not to own any more than can fit in a backpack, or at the most, in the trunk of a car, because the things you own, own you.” To break out of that box, try to make your own clothes, to grow some of your own food, try to learn to take care of yourself as simply as possible.

We waste so much food in America and I often dumpster dive behind natural foods shops. I know it sounds awful, but it’s not. They’ll throw away an apple with a little spot or bananas beginning to turn brown. Or they will accidentally nick a box of pasta with a knife when they’re restocking, and out it goes. This makes it possible for a whole subculture of people to live off of the throwaways of everyone else. We’d find boxes and boxes of juice that were still good, but because they would be out of date in a week, they couldn’t be shipped.

RTE: A couple of weeks ago I saw you stop on the street to check out a pile of clothes that someone had left for taking on their front lawn. You took a few wool and cotton pieces, and a few days later appeared with a new skirt that you’d made from the cuttings.

RAINBOW: People don’t need a different outfit for every day of the week, or even every day of the month, and it’s interesting to make your own clothes. Also, I have to say that if dumpster diving becomes cool, as it did in Seattle when college kids who were perfectly able to buy food did it for fun, there won’t be enough for the people who really need it. It’s the same with thrift stores. They got cool, and they got expensive. Then people who really needed dollar-clothes couldn’t afford them anymore.

I’d also say, If you can’t strip down to nothing, at least strip away the excess. I’ve got a job and a small apartment now, and it’s open to travelers coming through. This is the other end of travelling. Also, I found that 75% of the people who pick you up have hitched themselves at some point in their life. They’re giving back those rides. Now I’m the one who can say, “People have helped me, now I can help others.”

RTE: How would you contrast the Christian traveler scene with that of the American Christian world in general?

RAINBOW: We need instruction as much as anyone; we all fall into the same passions though in different ways. We travelers are quick to see the problems in society, but we still have a million problems inside ourselves that we haven’t seen; we are self-willed, rebellious and undisciplined. I believe that we all need each other and that the Orthodox Church in the U.S. needs the travelers, because comfortable Orthodox Americans need to see that they can and should live on less, especially with so many other people around the world suffering. But we travelers also need to see good examples of family (which many of us didn’t have), stability, and people who use things well. We’re all one body.

RTE: Seth, do you have anything to add?

SETH: I think the Church is complete on its own, and it’s important that people look beyond outer appearances and realize that folks who wander like this are often searching. We need to be open, to welcome everyone. Just as native Americans saw their cultures eradicated and the land despoiled by “Christians”, travelers have often seen the negative side of “Christian culture”. Orthodoxy can repair and mend these broken views of Christ and Christianity. As Orthodox we have an opportunity to show the broken people of this land that Christ loves all and wants everyone to find relief in these dark times. Truly Christ is the great Friend of Man. There are many lost and indigenous people who have had their dignity ripped out by those calling themselves Christian. This is not how it was meant to be, but we can look to the example of St. Herman of Alaska, who defended the weak and wronged. And I don’t mean just soup kitchens—we have to help restore their dignity. I hope I can one day do half as much as people like Fr. Paisius and Mother Nicole at St. Mary’s in Kansas City, both of whom are helping me heal my own soul.

RAINBOW: Yes. When I was in Alaska, I met Fr. Paisius DeLucia, a priest in the Bulgarian Church who runs an Orthodox school in Kodiak. We were so much on the same page. I was talking to him about how the punks need the Orthodox Church because it fulfills their ideals and longings, but the Orthodox Church also needs the punks: it needs to be awake and aware of the dangers of worldliness.

RTE: Do you still call yourself a punk?

RAINBOW: I think I’d rather just call myself a Christian, if I can even say that, but the punk scene really is going strong. For some it’s just music, but it’s also a do-it-yourself attitude. Make your own clothes, grow your own food, build your own house, fix your own car—or get rid of your car and build a bicycle. Stop depending on the government and on other people. Do as much as you can yourself. A lot of it is just rejecting pretty, happy, fake culture. If everyone was really joyful and content it would be great, but there’s a lot of emptiness behind modern life.

The punks are so ready for Jesus Christ and Orthodoxy. They’ve rejected this world and even if they’re drunk and angry and loose, they’re looking for something more and they won’t accept fake comfort—they’ve got to find what fills that empty space. Father Paisius said that the Christian punks are the society of St. John the Forerunner; they have left the world and are crying in the wilderness. The challenge is to do it in the right spirit, for God.

If anyone reading this would like to write us, we’d both love to hear from you.

Rainbow (Xenia) Lundeen and Seth (John) Haskins

c/o Rev. Deacon Michael Wilson

837 E 800 Rd.

Lawrence, KS 66047

orthodoxlove@yahoo.com

From: Road to Emmaus Vol. XII, No. 4 (#47).