During its historic past, the spiritual activity of the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi [one of the twenty monasteries on the Holy Mountain of Athos—Trans.] has proved to be twofold. On the one hand, the monastery has lived in hesychia (silence, stillness) and freedom from cares, which are the preconditions for deification; and, on the other hand, it has sent forth its deified and sanctified children as missionaries, so that they might offer a good witness to the Orthodox Athonite Tradition for the strengthening of the people of God—something not extraneous to the life of the Church throughout the ages. We can say that the monastery became very distinguished in this field, such that it undertook missionary work not only within Greece, but also in other Orthodox nations.

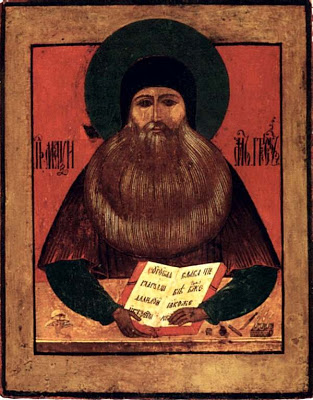

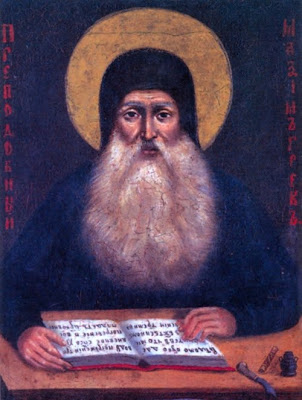

St. Maximos of Vatopaidi—better known as St. Maximos the Greek—was one of the most learned monks of his time, distinguishing himself as a theologian, philosopher, author, and poet during the first half of the sixteenth century, and became known as the “enlightener and reformer of the Russian nation.”

He was born in the city of Arta [northwestern Greece] in 1470 to a wealthy, illustrious, and pious family, and was named Michael Triboles. His parents gave him his basic education at the schools of Arta and Kerkyra (Corfu). At twenty years of age, he went to Italy, where he pursued higher studies for some fifteen years at the universities of Venice, The Garland of the Annual Church Calendar Padua, Ferrara, Florence, and Milan. One of the more distinguished biographers of St. Maximos, E. Golubinsky, maintains that, had the Saint ultimately remained in Italy, he would have become one of the most eminent university professors of his age.

St. Maximos, however, gave himself over to an intense search for an authentic way of Christian life, having seen for himself the nakedness of humankind bereft of God’s Grace while living in Italy, where Renaissance humanism was then flourishing. At the same time, moralism had turned the world to the senseless passions of hypocrisy, avarice, inhumanity, and dissoluteness. Thus, upon hearing about the monastic republic of the Holy Mountain and yearning to achieve the highest human calling—that of deification—and having discerned the vanity of every earthly glory and wisdom, he decided to dedicate his life to the Lord as a monk in this glorious cradle of Eastern Orthodox Tradition, eventually settling in the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi.

His departure for the Holy Mountain

At the Monastery of Vatopaidi, he lived in asceticism for approximately ten years. He exercised himself in the basic virtues of obedience and abstinence, thereby essentially avoiding all human passions, since he cut off his every will, desire, greed, and pride. His insatiable yearning for the acquisition of virtues and his enviable diligence in exercising himself therein rendered him a vessel of the loftiest virtues of humility, nonacquisitiveness, and love. By means, again, of these virtues, he constantly sacrificed himself for his fellow ascetics and fellow men. Simultaneously, he united his soul with God through unceasing prayer, becoming an abode of the Holy Spirit.

The monastery’s rich library also nourished the Saint spiritually; he found great delight in studying its books. From the library’s rare manuscripts, he garnered the wisdom of his predecessors in the Orthodox monastic tradition. At the same time, the example of the monastery’s other learned Fathers became a luminous guiding light in the Angelic, monastic life.

The monastery’s Fathers soon discerned the cultivation of his soul, so rich in virtues and spiritual gifts. They thus entrusted him with necessary work outside of the monastery, which the holy Father used as opportunities to strengthen our suffering Orthodox people, who were assailed by illiteracy, the bonds of the Turkish Yoke, and the heresies of the West.

In 1515, Grand Prince Vasily Ivanovich [of Russia] asked the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Protos of the Holy Mountain for an experienced, learned, and virtuous monk, who could translate Church texts into the Slavonic language and correct erroneous translations and copies of Holy Scriptures and Patristic texts.

Monk Sabbas of Vatopaidi was initially chosen, but he refused on account of his advanced age. The lot thus fell to the eminent Monk Maximos.

His mission in Russia

St. Maximos left the Holy Mountain in 1516. Representing the Russian people, Metropolitan Varlaam of Moscow and Grand Prince Vasily Ivanovich welcomed the Athonite monk and those with him.

Unfortunately, at that time the Russian nation was being scourged by new ideologies, which had slipped even into Orthodox ecclesiastical books, perhaps not fortuitously.

St. Maximos began his work of writing, translating, correcting, and exegesis. At the same time, his genuine Orthodox way of life soon came to attract the Grand Prince and the Metropolitan, as well as the Russian people and numerous eminent and distinguished people, who recognized in him a sagacious monk with the ability to resolve, by the power of God and his wise teachings and counsels, the multifarious problems pertaining to people of all social classes and walks of life. Thus, he began his advisory work chiefly before the Russian ruler and the Metropolitan, who directed matters relating to the State and the Church, respectively.

We should also note that St. Maximos was the first to initiate the Russian people into ancient Greek philosophy and literature, thanks to his many years of profound studies at Western universities. Moreover, he was the first to introduce the art of printing into Russia, owing to his close ties with the renowned Italian typographer and savant, Aldus Manutius.

Generally speaking, St. Maximos the Enlightener and Equal-to-the-Apostles acted resourcefully and wisely, taking care to educate a multitude of people, who subsequently continued his colossal work of enlightening Russia in Orthodox Christianity, for the salvation of the people and the glory and joy of the Church of Christ.

These cultural activities of the Saint underscore his manifold acts of beneficence, showing him forth not only as a missionary worker, but also as a civilizer of the Russian people, who at that time were in a state of illiteracy and ignorance.

St. Maximos’ missionary activities lasted eight years. He bore a heavy cross, however, with his work on behalf of the Faith; or rather, the Devil, the enemy of the truth, attempted to destroy St. Maximos’ work, though the Evil One ultimately failed in this regard, since the “grain of wheat fell on good ground and sprang up, and bore fruit a hundredfold” (cf. St. Luke 8:8).

Conflict with the political and ecclesiastical leadership

More specifically, owing to irregularities on the part of certain political and ecclesiastical figures—due, in large part, to ignorance—the Athonite Father was compelled to expostulate with and censure certain individuals, on the basis of the principles of the Gospel and in accordance with the ecclesiastical capacity afforded him by the Russian Church and the country’s royalty.

Unfortunately, however, not only did things not improve, but St. Maximos was now additionally confronted with the enmity of those he had censured, among them the Grand Prince and the new Metropolitan of Russia, Daniel, who disregarded the Saint’s sincere concern for their salvation and for the right direction of the Russian Church.

Thenceforth the Saint was to bear a heavy cross of imprisonments and tribulations unto death. Precisely these tribulations perfected St. Maximos spiritually, however, such that today the equal-to-the-apostles, confessor, martyr, and ascetic is regarded as one of the foremost illustrious children of the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi, and of our Orthodox Church in general. It is he who, by Divine calling, accumulated all of the charisms; and all of the aforementioned appellations befit him to such an extent that not one of them can be deemed an exaggeration.

St. Maximos censured representatives of the Church for living in a manner unbecoming to the clergy and monasticism, as well as for inappropriate behavior towards the people. At the same time, he also repri- manded political representatives for similar matters, just as St. John the Forerunner—who was put to death in prison for censuring the King for committing adultery—had done. Thus, St. Maximos became a confessor by upholding moral standards with strictness and by rebuking those who did not live morally, regardless of their office or rank.

He did not become conceited by the honors shown to him by the Grand Prince, nor by the fact that he was the foremost royal counsellor and ate with the Grand Prince at the same table for eight whole years, as if he were himself a prince. None of these things made him forget that he was a monk—and an Athonite monk at that—who had been called by Divine behest to correct the morals of the Russian people. Nor did he take into account that he would lose favor with the Grand Prince and representatives of the Church, along with the honors they showed him, by censuring them.

His imprisonment

He was condemned, as an alleged heretic, to life imprisonment in fetters and deprived of partaking of the Holy Mysteries. Placed in solitary confinement, he was forbidden to have any communication with the faithful. He suffered all of these things, as we said above, because he had censured his accusers for immoral behavior, using Christian morals as his basis. Likewise, he was prohibited from carrying on correspondence or reading books. The final prohibition was a martyrdom in itself for the learned monk-philosopher, since his spiritual nourishment and delight were derived from the study and writing of books.

Metropolitan Daniel, who was primarily responsible for St. Maximos’ ordeals, placed in his prison cell two cruel and inhuman guards, who tormented him without mercy for six continuous years. As St. Maximos later wrote to Metropolitan Makarios of Moscow: “Imprisoned, I was kept in bonds, dying from the cold, smoke, and hunger.”

His biographer, Kurbsky, writes that

“He suffered much from the burdensome bonds and the long confinement in a frightful prison ... being exceedingly beleaguered and mercilessly tortured, both physically and mentally, by intolerable ordeals for six years in iron fetters ... As a result of these tortures, St. Maximos would often fall completely unconscious, almost to the point of death. At one point, wishing to alleviate his affliction, he wrote a Canon to the Holy Spirit on the prison wall with a piece of charcoal, since he was not permitted paper on which to write. Under these conditions, he never grumbled or condemned anyone! At the end of his earthly life, St. Maximos would write a letter in which he prayed with regard to Metropolitan Daniel, who was the primary cause of his myriads of tortures: ‘May God not lay this sin to his charge’!”

During his first imprisonment in the Monastery of Volokolamsk, and, following that, during his second transfer to the Monastery of Otroch, he was confined to a damp and dark, subterranean prison, deprived of light and heating, and of every human consolation to which even the vilest of malefactors is entitled.

Who is capable of describing his martyrdom, and especially his deprivation of the Divine Eucharist? Only one who has come to know the love of our sweetest Jesus could describe such a martyrdom.

Despite the Saint’s protests over this harsh and unjust epitimion (penance), and despite his pleas at least to be permitted to partake of the Divine Mysteries—saying, with deep pain: “I ask that you vouchsafe me to partake of the All-Immaculate and Live-giving Mysteries of Christ, which I have been denied for seventeen years now ... Grant me, I beseech you, this favor ... save this lost soul ...” “... I seek mercy and benevolence ...” “... I ask for mercy; show me mercy, that you might also be vouchsafed the same Grace”—unfortunately, the clergy of iniquity did not pay him heed. They confined him without permitting him Holy Communion for eighteen full years.

Moreover, as we said above, his martyrdom was heightened by the tremendous pain caused by being enchained for six years at the prison of Volokolamsk, and then again during the first eight years of confinement in the prison of the Monastery of Otroch. In total, he spent fourteen years in iron bonds (1525-1539), and was imprisoned for a total of twenty-six years.

Dealing with his tribulations

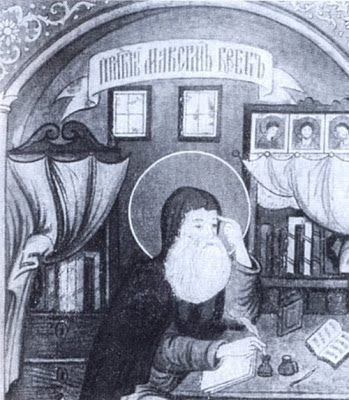

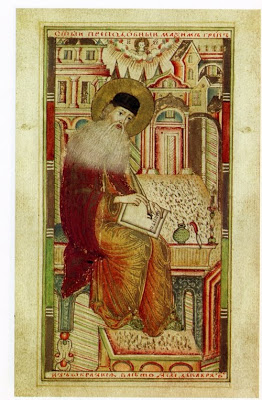

Saint Maximos suffered all of his ordeals with patience and without resentment. Never did he reproach those who had caused him to A specimen of the handwriting of St. Max- imos, from Codex 198, leaf 579, Holy Monas- tery of Docheiariou. undergo such great sufferings, nor did he ever depart from the bounds of spiritual nobility and meekness. This he achieved through humility. Emulating other holy Fathers, while protesting against his condemnation as a heretic and a blasphemer, he nevertheless accepted his trials as if they had been permitted by God on account of his sins.

Thus, he wrote to Metropolitan Daniel: “But I tell you in this regard that you have [unjustly] condemned me for heresy and prohibited me from partaking of the Divine Mysteries. As for my other many and innumerable sins, I am not able to open my mouth. I must not despair, however, but rather hope in God’s immeasurable mercy ...” And elsewhere: “The Just Judge, Who desires that all men be saved, Who has permitted me to undergo these afflictions on account of my many great sins, and not for heresy or blasphemy...”

The Saint’s patience was also due to Divine strengthening, in accordance with the Psalm: “According to the multitude of my sorrows in my heart, Thy comforts have given gladness to my soul.”

The consolations of the Holy Spirit were such that not only they equiponderated the Saint’s sorrows, his pains from the tortures, and his tears, but additionally they caused Divine love to overflow in his heart, becoming his “bread day and night.”

The venerable Father was also vouchsafed a vision of a Holy Angel, who descended into the prison and offered him the Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus. Following this miracle and his Divine vision and succor, in Divine exaltation he composed and wrote with charcoal on the prison wall the aforementioned Ode to the Holy Spirit, which begins: “O, the manna by which Thou once didst feed Israel in the desert ...” followed by “with Thy Bodiless Ministers, I also chant to Thee ...” which imply the vision of the Angel who transmitted to him the Body and Blood of our Lord.

As for the further Divine succor granted to him, who could know or tell of it? God guided him, through this hard path, towards perfection. We also see this from the exhortation by the Holy Angel, who appeared to him and said: “Maximos, be patient in these sufferings, that you might escape the sufferings of eternal chastisement.”

Thus, St. Maximos, by Divine revelation, became completely aware that he was fulfilling the Will of God when he was forlorn and reckoned an abomination by all, a stranger in a foreign land. In a state of extreme humility of spirit, he put into his heart that he was the lowest person on earth, humbled with Divine knowledge that the Lord had permitted his sufferings; for through the path of extreme humility He wished to guide him to spiritual perfection.

Living in seclusion and silence, he prayed unceasingly, with wordless groanings of the heart, noetically calling from the depths of his heart upon the Name of his sweetest Bridegroom, Jesus Christ.

Thus, through his martyrdom and through bearing the Cross of the Lord with knowledge, the Saint became perfected in Christ, completely dispassionate, a pleasant psaltery and sonorous cittern of the Holy Spirit, and a dwelling-place of the Holy Trinity!

St. Maximos was among the few monastic Saints who conducted their spiritual struggles devoid of a guide and human solidarity—without a spiritual Father or Elder to comfort and strengthen him as he bore his cross, and even without the solidarity of like-minded brothers, according to the saying: “A brother helped by a brother is as a strong and fortified city.”

He was faced with “external battles,” “imprisoned, kept in bonds, dying from the cold, smoke, and hunger,” but also with “internal fears,” lest he repine against God over the multitude of his tribulations or transgress God’s commandments by becoming angry with those who had done him injustice, revile them, or bear them resentment.

At the same time, a whole mob of other passions raged against him. The battle was gigantic, and the conditions under which the Saint struggled were not only incomprehensible, but even inconceivable to us. He conquered, however, with the alliance of the Lord, Who loved him and Who had given Himself over unto death for the sake of all.

His sentence is mitigated

Saint Maximos saved the entire Russian Church from prejudices, superstitions, and heretical beliefs that held sway at that time in Russia.

While imprisoned in the Monastery of Otroch (1531-1551), he was given relative freedom of communication by Metropolitan Akaky of Tver (following a sign from God), so that this light might not remain “under a bushel” (cf. St. Matthew 5:15).

Thus, while bound in chains for years in a dark, damp, subterranean prison, he tirelessly continued to write, translating sacred texts into Slavonic and composing, among many other things, anti-heretical works, for the sake of protecting and enlightening the Russian people. In addition, with fatherly affection, he once again began preaching, comforting the Christians who hastened to his prison cell to hear his advice and seek his prayers.

Several years after the imprisonment of Metropolitan Daniel, Metropolitan Makary of All Russia released the Saint from his unjust punishment of excommunication, which had lasted eighteen years (1525- 1543).

From time to time, he would fervently beseech to be liberated, so as to return to his beloved monastery on Mt. Athos, but never received a response. When Tsar Ivan the Terrible ascended the royal throne, the Greek monk repeated his appeal, but again without positive results. Likewise, Patriarch Dionysios of Constantinople (in 1545), Patriarch Germanos of Jerusalem, the Patriarch of Alexandria (on September 4, 1545), and the Monastery of Vatopaidi all sent requests to the Tsar to release St. Maximos.

In one of his own letters to the Tsar, St. Maximos wrote:

“Please deign, by the Name of the Lord, to show mercy to me, the wretch. Grant me to see the Holy Mountain, where prayer is sent up for the whole world. Restore me to the holy Fathers and to my brethren, who pray on your behalf. Yield in a Christian manner to their entreaties and tears. Do not wish to appear disobedient to the Ecumenical Patriarch, who is entreating you on my behalf. “

And elsewhere:

“Judge for yourself, I beg you, if I am worthy of hatred for all that I rightly corrected, and if I was justly slandered by certain ones as a heretic and denied communion with the faithful and of the Divine Gifts for so many years.... If, then, I speak rightly and credibly, show me, the wretch, your goodness and mercy, as a pious and unbiased judge, and acquit me of the unjust slanders and these ordeals, which I have been suffering for many years now ... Grant me, I implore your reverence, to return to the Holy Mountain, where I toiled in many and various ways both spiritually and bodily in hope of salvation, that I might lay down my bones there in peace.”

And elsewhere:

“Return me, most devout Tsar, to the venerable monastery of the Theotokos of Vatopaidi. Spiritually gladden its holy monks, your servants and fervent intercessors. Do not desire to grieve them.”

It is worth noting that in each of his letters the Saint pleaded to be returned to the Holy Mountain, repeating the phrase: “that I might lay down my bones there in peace.”

Yet his martyrdom continued. His return was deemed dangerous by the Tsar and Church leaders of the time, since the Saint knew all of the negative aspects of the political and ecclesiastical life of Russia, and they were afraid that he would hold them up to public opinion and reveal the ill will they had shown him.

His sentence is lifted

In 1551, the new Tsar, examining the entire affair with his dignitaries, who insisted on the Saint’s vindication, ordered that he be moved to the renowned Lavra of St. Sergey, thereby ending his sentence of imprisonment, which had lasted twenty-six consecutive years, without, however, permitting him to return to his homeland and his monastery of repentance, for the aforementioned reasons.

St. Maximos, by now elderly and exhausted from the manifold hardships of his life imprisonment, gave over his soul to the hands of our Lord, to be relieved of his toils and pains, on January 21, 1556, the day on which the Church commemorates his Patron Saint, Maximos the Confessor. On this day as well, his brothers at the Monastery of Vatopaidi had the custom of celebrating the Feast of the Panagia Paramythia (“of Consolation”).

He was around eighty-six years old when he reposed in 1556, and had served the Russian Church and its pious faithful until his last breath for a total of thirty-eight years, twenty-six of which he had spent in prison.

The Œcumenical Patriarch of Constantinople proclaimed the sanctity of Maximos the Greek in 1988. Following that, during the celebration that same year of the millennium of Orthodoxy [in Russia] in Moscow, he was glorified by the Russian Church. The Translation of his Relics took place on June 21, 1996 (Old Style), in the Church of the The Holy Lavra of St. Sergey, where St. Maximos lived during the last five years of his life.

The arrow marks the Church of the Holy Spirit, where his reliquary is kept. The Holy Icon of the Panagia, given by Grand Prince Vasily Ivanovich to the delegation of Vatopaidian monks who accompanied St. Maximos to Russia in 1517. Holy Spirit at the Lavra of St. Sergey, where his reliquary is kept. A portion of his Relics were handed over to the Monastery of Vatopaidi, the monastery of his repentance, on July 8, 1997 (Old Style), in the Church of the Panagia of Kazan by Patriarch Alexey of Moscow and All Russia. The celebration of the Translation of his Relics to the Monastery of Vatopaidi took place on July 14, 1997 (Old Style).

* * *

The example of St. Maximos should give us courage. The discipline of the Lord through ordeals did not destroy him; rather, with faith, prayer, and virtue, he drew upon Divine strength and remained patient throughout indescribable temptations. We recount the lives of the Saints in order to follow their examples, to gain strength, and to approach God with orthopraxia, by Church attendance, confession, and partaking of the Divine Mysteries. Every one of us will bear, according to his strength, the Cross of his Resurrection. Knowledge of the path towards our Divine Transfiguration is necessary, and in particular for the Greek nation, which led so many other nations to knowledge of God by means of its wise Saints, who are equals to the Apostles.

We pray that our All-Good Triune God, who “worketh hitherto,” might ever send forth worthy and holy workers, like the great and tireless Saint Maximos, to His vineyard, for the salvation of all. We also pray that God, through the intercessions of this our holy Father, grant His Grace for the preservation of unity of Faith and bonds of love in our One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church of Christ.