Source: Theology That Sticks

Whatever we think about the controversies over same sex marriage, or the Obamacare contraception mandate, or [insert your chosen fight du jour], one lesson stands out: faith cannot be shoved into a corner.

For all of its private aspects, religion is a public affair. Whether a person considers himself a cultural warrior or just a humble and faithful adherent, there are always social implications to belief.

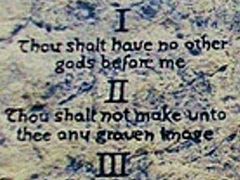

Those implications are first evident in small matters of individual behavior. Honesty with one’s neighbors and respect for their life and property are, for instance, social aspects of following the Ten Commandments. But the same basic fact applies in larger political contexts as well.

Public Expression is a Given

Some reflexively suggest that politics should be hermetically sealed from religion. But that demands an unnatural segmentation of the human person and the motivations that drive human action. It’s no good to say that faith should inform your life in one context, but—whoa!—hit the kill switch in another. A Christian is a Christian in all settings.

Follow these words from French atheist and feminist Christine Delphy:

[W]e have constantly been exhorted to consider religion a “private” affair or even a “personal” one, which must only ever be expressed when you are by yourself. It’s a bit like going to the toilet in the privacy of your own cubicle.

This is obviously absurd: it would mean having the right to think whatever I like (within my own conscience) but not to say it. . . . Freedom of expression means nothing if it is just the freedom to communicate with . . . myself. If other people can’t see or hear it, it would be materially impossible to prohibit it, in any case; and as such, it wouldn’t need protecting. So the freedom of expression we defend is always, by definition, freedom of public expression. The word “public” has to be taken as a given.

If a free expression of religion means anything—and this goes for Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, etc.—it must mean that adherents are free to influence society with their views. This is especially true in an open, liberal society such as our own. It’s the curse and the blessing of our system.

Yes, we can declare certain things off limits. The Bill of Rights is an attempt to do that. But that won’t stop arguments from being made or minds being changed. And in the long run this is true even for prohibited expressions of faith.

Laws Reflect Hearts

Christianity was not always tolerated. It nonetheless had a transformative effect on the world.

“We cannot separate culture from religion any more than we can separate our life from our faith,” writes Catholic historian Christopher Dawson. “As a living faith must change the life of the believer, so a living religion must influence and transform the the social way of life—that is to say, the culture.”

It’s the inevitable outcome—no different than, to use Jesus’ metaphor, adding leaven to a lump of dough. “Even a Christian minority,” says Dawson, “which lives a hidden and persecuted life ... possesses its own patterns of life and thought, which are the seeds of a new culture.”

That’s a sentiment both hopeful and sobering. On the one hand, take heart: no repression will ultimately prevail. We have the entire history of the church to validate that judgment. On the other, watch yourself: not only will laws against public manifestations of Christian faith prove futile, so will laws against any faith.

Beware those who think stacking the deck with statutes will somehow keep the worst aspects of, say, Islam from sinking its teeth into a society. Laws reflect hearts; they rarely change them—except perhaps in the opposite direction desired by the legislators. Coercion is infrequently met with gratitude.

Taking the Hit, Walking the Mile

Given that a person’s faith speaks to all areas of his life, it is natural to see that faith expressed in all areas of his life. If there are believers, in other words, they will have an effect—sometimes commensurate, sometimes not, to their numbers.

It’s an act of aggression for the state to force a religious believer be something in one setting and something else in another. The Christian may well succumb to that aggression, just as the Beatitudes might suggest—turning the other cheek, walking the extra mile. But it is a form of violence to the person, just as surely as striking a man or forcing him to march.

And it’s important to remember that sometimes taking the hit and walking the mile is the Christian response. Recourse to lawsuits and legislation is an option. But it’s not the only course of action and sometimes not the best.

In whatever form it takes, martyrdom is also public.