I would like to open one of the little-known pages of the book of the imperial Romanov family, and to remember its last legitimate male line descendant, who spent almost all her life in the USSR (as a class enemy) and post-Soviet Russia.

I got acquainted with Talia (she asked me to call her by this affectionate form of the name “Natalia” during our first conversation) by telephone in the summer of 1996. We agreed to meet in her flat near the “Molodezhnaya” Moscow metro station. She waited for me near the entrance of her block of flats, sitting on a bench surrounded by two mongrels, who, as she said, she fed and loved madly. The dogs playfully hung about, licking her hands and trying to reach her face.

“They are my best friends,” said Talia, offering her cheek for the dogs’ kisses. “They are more faithful than people.”

When we were about to go to her flat, Talia, to my surprise, took her crutches and suggested:

“Let’s walk up the stairs—for physical exercise. I like to walk this way.” And easily maneuvering with her crutches, she climbed the stairs to the sixth floor, to her one-room flat. By the way, she seldom locked her entrance door—only when she went away.

“Whom should I be afraid of?” Talia used to say. “Some people may install five doorlocks but they will be robbed all the same. Anyway, there is nothing to steal in my apartment. Maybe they’ll kill me? I am not afraid. My life is going hand in hand with the Lord; I rely on Him in everything.

Talia did not allow me to call her by name and patronymic because she, born Princess Natalia Aleksandrovna Iskander, was for most of her life called Natalia Nikolaevna Androsova, under the patronymic and surname of her stepfather. And when she was recognized as heiress of the House of Romanov her surname became Iskander-Romanovskaya.

Even under Stalin Talia began as far as possible to collect information on her ancestors, tying the broken threads of fate.

“To be a grandaughter of the Grand Duke and great-great-grandaughter of Nicholas I—was a death sentence,” she related. “My mother was a very cautious person; life taught her lessons, and she never hinted that we were related to the tsar. But some family photographs of the Romanovs always stood in our house—they were never hidden. I looked at them, knowing that they were our relatives, but nothing more. And when I grew up I learned who my ancestors were.

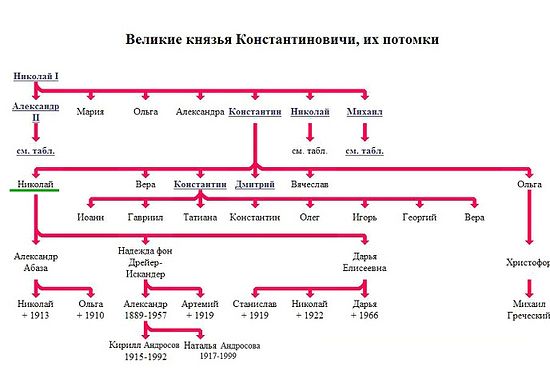

During our first meeting, Talia briefly related to me the history of her lineage. Thus, one of the sons of Tsar Nicholas I, Grand Duke Constantine Nikolaevich (brother of Tsar Alexander II) - had three children: Grand Dukes Nicholas and Constantine, and daughter Olga (who later became Queen Olga of the Hellenes). The elder son, Nicholas, who was Talia’s grandfather, was famous for his desperate fearlessness and reckless behavior. In 1873, as part of the Russian Expeditionary Corps under the command of General Skobelev, Nicholas as a colonel participated in the campaign against Khiva (a former khanate of Central Asia on the Amu Darya River: divided between the former Uzbek and Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republics in 1924) and was awarded with the Order of St. Vladimir of the third degree for personal courage. Fascinated by Central Asia, he also got carried away with oriental studies, took part in work of the Russian Geographical Society, and insisted on organizing the Amu Darya expedition for examination of the newly annexed lands. Nicholas was also thoughtlessly involved in temerarious love affairs. His romance with an American woman named Fanny Lear that lasted several years led to a quarrel with his parents. But the worse was still to come. It was said that for this American woman Nicholas stole and sold family treasures. And when diamonds disappeared from the mounting of an icon that had been given to Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna by Emperor Nicholas I on her wedding day, Grand Duke Nicholas was publicly accused. Though there was no compelling evidence against him, Emperor Alexander II at once declared his nephew insane (in order to avoid a great scandal) and sent him to Orenburg in 1874.

Nicholas Konstantinovich again demonstrated his precariousness and penchant for reckless deeds by secretly marrying the daughter of the Orenburg police chief, Nadezhda Aleksandrovna von Dreyer in the winter of 1878. This morganatic marriage resulted in his loss of the grand-ducal title and the right of succession for all posterity. Nearly all the Romanovs condemned Nicholas. Only his brother, Grand Duke Constantine Konstantinovich (a prominent poet, K.R.) did not support the imperial house members in this. “How long will this trying situation last, from which there is still no way out for poor Nicholas? Even the meekest person could be jolted out of a patient attitude, but Nicholas still has enough strength to endure his exile and moral prison,” he wrote at that time. With the assistance of Constantine Konstantinovich, Emperor Alexander III, who had then just ascended to the throne, allowed this morganatic marriage to be considered valid, but nevertheless sent Nicholas with his spouse to the newly conquered Tashkent—one of the remotest points of the Russian Empire at that time.

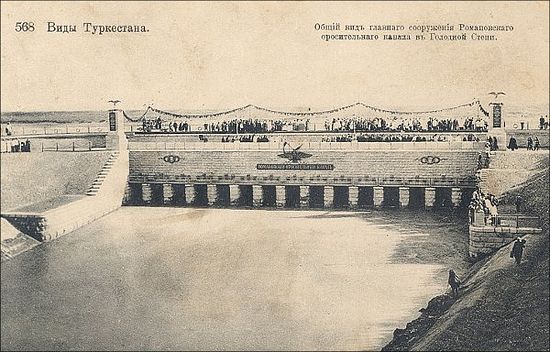

First, “the Tashkent prince", Nicholas Konstantinovich, lived under the name of Colonel Volynsky, was involved in the construction of irregation system in the barren steppe for which the grateful local inhabitants nicknamed him "Iskander", that is, "Great". This nickname, which became a surname, was inherited by Nicholas Konstantinovich’s sons, Artemy and Alexander (Talia's father).

General view of the Romanov irregation channel in the barren steppe, built with funding from Nicholas Konstantinovich

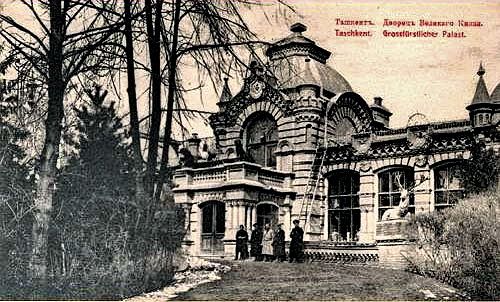

General view of the Romanov irregation channel in the barren steppe, built with funding from Nicholas Konstantinovich In 1900, under Nicholas II, by intercession of Queen Olga of the Hellenes (sister of Nicholas Konstantinovich) Artemy and Alexander Iskander were allowed to study in St. Petersburg. After the military school Alexander did military service in the capital and married a Polish woman named Olga Rogowska. They had two children: Kirill was born in 1915 and Natalia in February 1917. Family members tenderly called her Talia, or Talechka. When the Revolution was about to happen, the family moved far away to Tashkent, to their grandfathers palace. Duke Nicholas Konstantinovich became Talia’s godfather. In 1918 he was executed by firing squad.

“I always felt connected with my roots,” Talia used to say. “This can be described as ‘the voice of blood’. I would not say that I used to stick up my nose, but there was something inside me that made me ‘hold my head high’. And I did. I never stooped, under any circumstances. Now I realize that that was not always to my benefit; maybe at times I should have pretended, I should have made up to someone and shed a tear. But I always held up my head and smiled, even at time when I could have screamed in pain. I read how the Bolsheviks had tortured the family of Nicholas II in the Ipatyev House and thought, ‘Oh my God! How could such young girls, the Grand Duchesses, have such great fortitude? They had to care for the wounded, to work in the yard... And they neither grumbled or complained.”

After the beginning of the First World War, Talia’s father went to the front “for the Faith, the Tsar, and Fatherland;” and when the civil war broke out he fought in the Crimea in General Vrangel’s army with whose remainder he moved to France in 1919. Like the majority of Russian emigres in Paris, he changed many jobs—as a driver, a night watchman, and a cook. And to the end of his days he did not know what became of his wife and children who had remained in USSR.

“I recall how father held me in his arms, and it was such inexpressible happiness,” Talia recollected. “When I go to church, a similar thing sometimes happens during the service—as though I am dissolving in happiness, it is embracing me, like my father's arms, and my soul feels such peace. The thread between my me and my father was never broken, I always felt that he was somewhere praying for me, helping me in the most hopeless moments of my life.”

Early in the 1920s, Talia's mother married Nikolai Androsov. He saved Natalia and Kirill, giving them his patronimic and surname. In 1922 the family moved from Tashkent to Moscow, where they lived in a communal apartment in Plyushchikha Street. Until the fourth grade Talia studied privately with two noblewomen who were sisters, with etiquette and foreign languages among her subjects. But this relatively happy life did not last long: a neighbor Bolshevik informed on the “disloyal” tenants to the NKVD, and the Androsovs had to hastily move to a basement on Arbat Street, where Talia lived until 1970.

Talia with her elder brother, Kirill

Talia with her elder brother, Kirill After seven years of school Talia realized that there was no way open for her to go to any college or institute, so she had only occasional earnings to make ends meet, working as a draftswoman or a typist. But Talia found a real outlet for her impetuous temperament in the “Dynamo’ sports club.

“I always was an adventurous person; I loved speed, galloping on horseback. I went to a motorcycle club, tried new motorcycles,” she recounted. “I inherited this fearless character from my father. As a club member I once took part in a sports parade on Red Square. I imitated a statue of discus thrower, standing immovably on a giant platform, and floated past the mausoleum tribunal where Stalin stood. What did I feel at that time? Certainly not pride. I thought: all of us are walking under God—leaders, princess, and workers, and we don’t know what will to happen to each of us in the future. Yesterday the tsar was overthrown, and maybe tomorrow the communists will suffer the same fate. Of course, I thought it without malevolence.

Natalia Androsova

Natalia Androsova “I again rode a motorbike on ‘the wall of death’, - Talia related. “Many times I fell down; I hurt and bruised myself so badly that doctors predicted that I would walk on crutches for the rest of my life. But I rode the motorbike again and again. And I never allowed myself to grumble and bemoan my fate. Then, in the 1940s, I lost one knee: I tumbled down together with my motorbike from a great height. I looked, and saw bones jutting out of my knee. ‘Take me to hospital,’ I said then. But a year later I rode on ‘the wall of death’ again. And so it continued untill 1967.

Natalia Aleksandrovna Iskander-Romanovskaya

Natalia Aleksandrovna Iskander-Romanovskaya During the Khrushchev ‘thaw’, Soviet newspapers wrote much about the fearless motorcycle racer and, possibly, it was thanks to this fact that the widow of Talia’s father from Paris recognized her.

“She wrote me a letter that was passed to me in Moscow through acquaintances,” Talia recounts. “Thus I learned that my father had died in 1957 and had been buried at a graveyard in Nice. For some time she and I exchanged letters; she was a very kind-hearted Russian woman, and once sent me several stories written by my father. As I read them, it seemed as though I was speaking with him, as if he were alive. I feel we are related not only by blood, but also in spirit. I believe that he and I would have been close friends.”

I concluded my earlier publication on Talia with the question, “What do you dream of?”

“Of visiting my father's grave,” she replied simply. “I ask the Lord neither for health (the health I have now will suffice) nor for a larger flat—I can hardly walk in my own flat with crutches. Why would I do with a palace? But my heart aches for my father.”

It was a “boomerang” thrown to the world; and, like American Indian hunters’ weapons, it returned with game. But it is not my merit. God provided that a certain businessman called up the editorial office and informed that he was willing to sponsor a trip for Talia with an escort to France for a week. That news touched me so much that it nearly made me weep for joy. But Talia did not bat an eyelid, when I came to let her know about that. She expressed no excitement at all, only crossed herself.

“Well, then let’s go!” she instantly decided.

“Excuse me, Talechka, are you sure that your health will not give you trouble?” I expressed my doubts, not without reason, since Talia was then eighty years old.

“The Lord will never fail me! I have a great confidence in Him,” and her face lit up with joy.

And, putting herself in God's Hands, Talia set off on that week-long journey—not a week-long trip, but, rather a journey that embraced all her life.

The grave of Alexander Nikolaevich Iskander

The grave of Alexander Nikolaevich Iskander Talia did not share with me the agitation common in such moments, and did not expose the whole range of her emotions, as she sat down on a bench near her father’s grave. I saw her face at that moment—so bright and peaceful. And not a single tear. She carefully wrapped a handful of earth from her father's grave in a kerchief and with a sense of having fulfilled her duty she came back home.

Natalia Androsova (Natalia Aleksandrovna Iskander-Romanovskaya).

Natalia Androsova (Natalia Aleksandrovna Iskander-Romanovskaya). Talia passed away in July 1999. At that time I was expecting a baby and, to be honest, avoided any communication. I blame myself for not having given her enough attention in the final months of her life. What can be easier: to call up, to ask how things are going, to support by kind words... She was very lonely and so much needed sympathy. Having been disillusioned by human-beings on more than one occasion, she fell in love with dogs. I repent. And already for the fifteenth year, when I submit commemorative lists for the departed at the Liturgy, I always write in block letters, ‘for Natalia’. But in my mind repeat, ‘Talechka’.