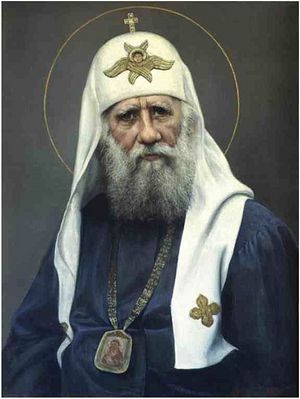

In 2015, the Russian Church celebrated two important anniversaries of Holy Patriarch Tikhon: February 1—150 years since his birth, and on April 7—ninety years from the day of his repose. Patriarch Tikhon captained the ship of the Church through the bloody storm of anti-ecclesiastical persecution inspired by the godless leaders of the communist regime, who had seized power in much-suffering Russia.

Patriarch Tikhon is one of the most venerated saints of our times. He has three feast days: September 26/October 9 is the day of his canonization, March 25/April 7 is the day of his repose, and November 5/18 is the day he was chosen as the Patriarch of All the Russias.1 But despite the many years that Patriarch Tikhon’s life and service have been studied, there are still many blank spaces in his biography.

On the eve (November 17) of a conference held in the St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Humanitarian University on the life and service of Patriarch Tikhon—the veneration of him, the manner of his sanctity and his place in the history of Russia, we have asked Archpriest Vladimir Vorobiev, the director of the largest center for the study of the history of Russia’s new martyrs and confessors and rector of St. Tikhon’s University.

—Fr. Vladimir, what role did Holy Patriarch Tikhon play in the history of the Russian Church and the history of Russia?

—This year marks the ninetieth anniversary of Patriarch Tikhon’s repose, which occurred on the feast of the Annunciation of the Mother of God—April 7, 1925. He died in the Bakuniny hospital, not far from the Monastery of the Conception on Ostozhenka Street. When he died, everyone suspected that he was poisoned. Although it was written many times that he “had not been poisoned,” he died “simply from a heart attack,” nevertheless, the version that he had been poisoned has not been dismissed because it is highly probable. This version has never been proved. I do not know whether it can be proved, but there has never been any attempt to investigate it. If it is poisoning, then Patriarch should be called a hieromartyr. If his death was from a heart attack, then it is anyway the death of a confessor.

St. Tikhon lived under conditions of serious persecutions against the Church and went through seven years of Patriarchal service as truly a way of the cross, the path to Golgotha. These very years led to his untimely end. He died at sixty years of age; that is, he did not live a very long life.

Today, looking back at the history of the twentieth century, we can say that Patriarch Tikhon is one of the greatest Russian saints, and he undoubtedly stands among the greatest universal saints. He was chosen by the most remarkable Council in the history of the Russian Church.

—Please remind us how this election took place.

—Preparation for the Council of 1917 went on for eleven years. The delegates were chosen democratically, without any political pressure. It was very representative [of society]—over 500 delegates.

The Patriarch was also chosen in a remarkable way. First, twenty-eight candidates were chosen. Then three were chosen out of these according to the number of votes. Then the Vladimir icon of the Mother of God was brought from the Dormition Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. The Kremlin had already been occupied by the communists, and therefore no services could be held there, so the icon was brought to the Church of Christ the Savior. In this church, the holy hieromartyr Vladimir (Bogoyavlensky) served the Liturgy; he was the first hieromartyr of the new martyr bishops. After the Liturgy and a special moleben before the Vladimir icon, Elder Alexey of the St. Zosima Hermitage drew the lot with the name of Patriarch Tikhon. Operating in the election was an amazing unity of the people’s active participation and God’s will.

Patriarch Tikhon headed the Church during the most terrifying persecutions against Christians in world history. We have more than sufficient grounds to say that Patriarch Tikhon stands at the head of the army of new martyrs.

He himself suffered persecutions from the very first days of his Patriarchy.

—Could you cite some little-known episodes from the period of his persecution?

—One day the Patriarch was informed that a whole train car of sailors was coming from Petrograd to arrest him, and he was asked to leave the Troitsky podvorye where he was living until 1922. This was in the evening, when Patriarch Tikhon was going to bed. He listened and then answered, “I’m not going anywhere.” The sailors arrived the next morning, disembarked, had a meeting on the platform, got back into the train, and went back to Petrograd. God Himself preserved His saint.

Everyone knows the testimonial Patriarch Tikhon wrote to the Bolsheviks, they know about his epistle with the anathema against iniquitous Bolsheviks. He tried through his epistles to protect the Church from the persecutors and bandits. In 1922 he was arrested. He was interrogated in court. A brochure of this interrogation with his comments survives. Then there was a year of strict imprisonment in Donskoy Monastery. From there he was taken for interrogations to the Lubyanka. He spent some time in the Lubanka prison. There is very little known about this.

The politburo pronounced the death sentence on him. Not the judge, but the Politburo itself made this secret decision. The sentence was not carried out, because the people’s commissar for foreign affairs G. Chicherin convinced the Politburo that the murder of Patriarch Tikhon will not be useful to the soviet government. The entire Christian world—in Europe and America—rose to protect the Russian Patriarch. The world “abroad” threatened the Soviet Union with what would now be called economic sanctions. It was decided not to shoot the Patriarch, but to demand a letter of repentance from him instead. Having received what they wanted, they released him.

—Couldn’t this be viewed as a sign of weakness?

—Patriarch Tikhon, of course, could not in any way have known what was going on in the upper echelons of the Bolshevik government—after all, he was a prisoner. How do Christians act in such cases? They ask God’s will. The guards who were watching him wrote in their diaries, “The old man is good to everyone, only he prays all night.” He prayed, and the Lord instructed him on what to do. Patriarch Tikhon agreed to sign the “repentance letter” that compromised him.

When he was released, the provocation activities of the “Living Church” immediately collapsed. A huge number of people understood what was going on, stopped going to the Living Church churches, and returned to Patriarch Tikhon. The clergy that had joined the Living Church came to the Patriarch with repentance. The Patriarch’s “repentance letter” did not damage his authority in the people’s estimation. The people knew that Patriarch Tikhon was a holy man.

The Bolsheviks arrested the holy Patriarch’s closest zealots, put them in prisons, sent them into exile, and executed some of them. Before his eyes they closed churches, monasteries, and theological schools; they confiscated holy shrines and opened reliquaries. Many archpastors could not summon any courage and tried to “agree” with the Soviet authorities, going in this way against the head of their Church. Patriarch Tikhon had at times to stand all alone against the soviet persecutions and seek the right path for the Church.

Even while he was alive, the soviet newspapers slandered Patriarch Tikhon unremittingly, humiliated him and mocked him. When he died, a falsified “will” was published in him name. But no one believed this falsification. Those who knew Patriarch Tikhon believed that he was a holy man. The people trusted him limitlessly, as a saint. Patriarch Tikhon possessed moral authority, which turned out to be an extraordinarily powerful force that united the Church, the clergy, and the entire Russian people.

When Patriarch Tikhon reposed, even worse times began for the Church. The lack of a spiritual leader produced adverse consequences. After his death the soviet authorities began picking people who suited their purposes to fill the position of patriarch. As long as the Patriarch was alive he could be arrested, but it was impossible to compromise him. The people trusted him.

There are firm grounds for speaking about the universal significance of Patriarch Tikhon’s heroic labor. The twentieth century is one of the most difficult epochs in human history, when materialism, atheism, and communism spread all over the entire globe, like a plague; when revolutions and antichristian persecutions started happening everywhere. Science claimed that Christ was a legend, a myth, that He never existed. And during this very time a giant of the Christian faith arises! A true Christian, who manifests Christian sanctity on the Patriarchal throne! A flame of confessing faith stood on a candle stand seen by the whole world, and glorified our Heavenly Father.

Patriarch Tikhon is the image of an Orthodox saint, who stood alone against the hurricane of bloody evil: revolution, civil war, mass violence, executions, and murders. They threatened to kill him also, and sent assassins on several occasions. He did not run away from death.

The only thing that he held dear was service to the Church. He understood that the Lord had placed him as a lighthouse that should shine in the darkness and light the path to Christ.

His circulars are patristic teachings to all Christians for all the remaining ages.

—What other significance does Patriarch Tikhon’s work have?

—Patriarch Tikhon, like all holy people, was inwardly very free. He blessed and thus legitimatized, as Patriarch and as a saint, frequent Communion of the Holy Mysteries of Christ. He called the people to this. This blessing has particular meaning to us.

He blessed people for the labor of confession and martyrdom. He showed by his own example how the Church can be victorious over the most terrifying, unbelievable evil.

He showed that the Church can be governed by holy bishops, even if it is deprived of administrative forms. And its life, though outwardly disastrous, is an extraordinary example of faith. The Church called forth these saints. In this sense, the communist persecution was the brightest page in the history of the Christian Church. When has such a host of saints made known? And the Patriarch was their leader. The warriors of Christ walked under his omophorion. This was unique in history.

If you look at our history in the historical scope of the Universal Church, then we see before us a terrifying picture of a spiritual war, when persecutions are not happening in some distant province where an emperor comes and makes a local pogrom. No, a whole enormous country, the largest country in the world, was subject to persecutions. Throughout Russia the Church was declared illegal. And not just as a temporary measure, but with the intent of destroying the whole Church. The entire episcopate was suffering repression. Almost all the priests were either killed or imprisoned. Before the [Second World] war, in Russia only a few bishops and about 100 priests remained free.

But the Church proved that it is not an earthly organization that can be closed or destroyed. It is the Body of Christ. It showed that it is not bound by earthly forms. You can destroy all the Church’s earthly forms of it life, but it will not become any weaker from this. It answers deadly persecutions with the feat of confession and sanctity, and it is victorious.

If you imagine a painting, you would have a battle between good and evil, the righteous and the sinners, and in this picture, at the head of the army and among the warriors, following after Christ and the angelic powers, goes Patriarch Tikhon leading the army. The Gospel shows us a spirit of victorious opposition on the way of the cross. These were Christians who took up their cross and followed after Christ. There were hundreds of thousands of them. Patriarch Tikhon is a symbol of the era, and an image of ascetic labor in the Church.

Our Patriarch

—Which of Patriarch Tikhon’s personality traits are especially important to us?

—Those who knew Patriarch Tikhon testified that he was a man of unbelievable humility, meekness, and love. He was perfectly simple. He was a stranger to emotional pathos. He was simple in life, and how he related to people. I say this because my grandfather knew him. He was the dean of Moscow diocese and went to diocesan councils under Patriarch Tikhon.

In Sergiev Posad (then called Zagorsk) there was a remarkable elder, Fr. Tikhon Pelikh, the rector of the St. Elias church beyond the Holy Trinity St. Sergius Lavra. He was born to a peasant family, and sent to the army. Here is his personal account. He reached Moscow in his soldier’s overcoat and came to the church where Patriarch Tikhon was serving. He was a young fellow, hungry and cold. He related: “I myself don’t know how I ended up in the altar. Some kind of power led me there, and pushed me towards Patriarch Tikhon. I didn’t know what to say. I went to get his blessing. The Patriarch affectionately asked me, “What is your name?” I answered, “Tikhon”. He said, “My name is also Tikhon.” I don’t remember anything after that, only that the subdeacons pulled me out of the altar by the edge of my coat.” All who came into contact with Patriarch Tikhon were blessed with grace and love.

It is impossible to convey how people loved Patriarch Tikhon. When he came to serve in some regional town, the factories stopped their work, and all the workers came out to greet him, not resuming work until he had gone. His saintliness, love, and dedication to God’s will brought Christians together, and helped them withstand the terrible aggression coming from the dark world.

Patriarch Tikhon showed us the ascetic labor by which the Russian Church must go in the last days, because he by his own labors renewed Orthodox life in Russia.

At that time revolutions were happening, there were renovationists introducing reforms to renew the Church, to create a “Living Church”. But Patriarch Tikhon really “renewed” the Church life, again manifesting the sanctity of the Church, and the labor of an archpastor. This is the main path of renovation. He could not bring to pass the reforms decided upon at the Council, but he renewed the spirit of the first Christians, who were ready to give their lives to God and to defend the Christian faith even unto death. We need this spirit also. Our times are very complicated, and the aggression of darkness is not slackening. We can oppose this aggression if we are inspired by the labors of the saints.

<…>

—What does Patriarch Tikhon mean to you?

—I knew about Patriarch Tikhon from early childhood, because he was very revered in our family. My grandfather associated with him personally. We preserve like a relic a Paschal egg that Patriarch Tikhon gave our grandfather. We have a whole series of documents signed by him.

I knew an old lady who suffered in childhood from a terrible case of epilepsy—eighteen seizures per day. Then she was a girl who didn’t believe in God. On the night of his repose, Patriarch Tikhon appeared to her and blessed her. She was healed and became a deeply believing Christian. There are very many such testimonies to the sanctity of Patriarch Tikhon. For me he was a saint even before his canonization. I would go to his reliquary in the Donskoy Monastery. I especially learned much about him through Mikhail Efimovich Gubonina, who served in the altar at Patriarch Tikhon’s services, and deeply revered him and collected many documents about his life.