I had occasion this week to stand in a group of scientists. I was burying one of their own. The city I live in is a “science city,” the location of one of the primary national labs in the US. I have lived here for over 25 years. I have gotten to know many scientists. When they are at their best (and science at its best), wonder forms a large part of their world. To do research is not something you do because you know the answers, but because you don’t. Something is being sought.

This is, essentially, a religious point of view. To recognize that the world is wonderful and larger than you know, is to begin to understand your place within it. You do not control it, nor can you ever. It is too frequently the case that people speak of God as though they knew very well what (who) they were talking about. In a nation where confrontation and defensive positions often overwhelm everything else, what we do not know is quickly overlooked. We dare not admit what we do not know for fear of being shouted down or dismissed. But it is absolutely essential to come to God not knowing.

Christ said,

Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives, and he who seeks finds, and to him who knocks it will be opened. (Mat 7:7-8)

But fulfilling those verses requires that we admit that the door seems closed, that there is something we have not received, and that we have not found what has been offered.

I do not mean by this the quite commonly abused use of ignorance. There are many who feign ignorance in order to undermine others and to foster their own agenda. “Since no one can know that, I’ll do what I want.”

But there is also a problem with embracing the Orthodox faith, as though you know it. The dynamic of seeking can easily come to an end while we substitute using our energy for defending something we do not yet know. The result is anger and stress. If you are frequently angry about your Orthodox faith, you have likely lost your mooring.

I saw this quote from Fr. Thomas Hopko recently:

The Scripture is very clear: If you want to find yourself, lose yourself; you want to fulfill yourself, empty yourself; you want to be great, be the least; you want to be first, be the last; you want to be rich, become poor; you want to be wise, become a fool. If you want to rule, become a servant…really, Orthodoxy is paradoxy. That’s just what it is.

The dynamic between the life of asking, seeking, knocking, and the life within a received Tradition is easily lost on us. For those who have fled to Orthodoxy from the constant erosion and madness of modernity, the habits of a rearguard action, always living in a defensive posture, are hard to shake. There is always the haunting feeling that what has happened elsewhere can happen here. And, it is much easier to expend our energy in defending thoughts and ideas than it is to pour ourselves out by seeking to know what (and Who) is behind and beyond those ideas.

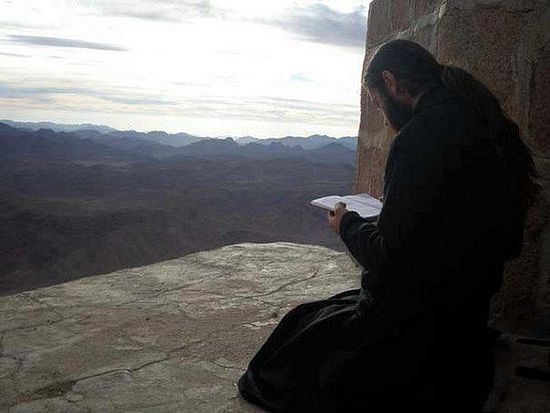

The truth is that there is no possibility of truly seeking until we stand within a Tradition. Orthodoxy, more than a set of answers, is the living communion with the life of those who have shown that there are answers. They are markers of the pathway that rescue our searching from vanity and delusion. To a large extent, the monastic presence in Orthodoxy exists to preserve this dynamic.

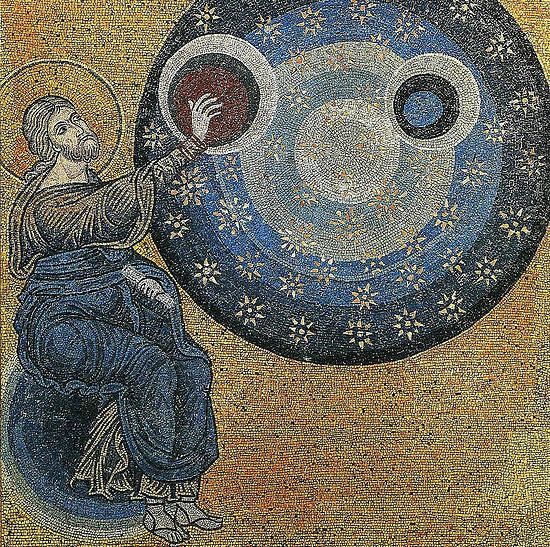

It has long been noted that the rise of monasticism occurs just before the end of the Roman persecutions. At the very moment that a comfortable complacency was offered to the Church, a settling-in to a protected place within the empire, the deserts began to fill with men and women who took the pilgrim’s search to its most extreme expression. The very time of the Church’s peace also became the time of doctrinal and administrative consolidation. The great Councils are everything the Church professes: true and certain expressions of the faith of the Apostles.

The great challenges of our contemporary world can make those conciliar pillars appear endangered. Indeed, we are commanded to “faithfully contend for the faith once and for all delivered to the saints.” (Jude 1:3) But the conciliar pillars are not that faith itself: they are verbal icons of Christ. However, the faith once delivered is Christ Himself.

It’s in this manner that the Lenten road to Pascha serves as the model for the whole of our Orthodox life. We do not fast and pray, give alms and repent for the sake of affirming a doctrine. Rather, we are in the position of St. Paul who cried:

Yet indeed I also count all things loss for the excellence of the knowledge of Christ Jesus my Lord, for whom I have suffered the loss of all things, and count them as rubbish, that I may gain Christ and be found in Him, not having my own righteousness, which is from the law, but that which is through faith in Christ, the righteousness which is from God by faith; that I may know Him and the power of His resurrection, and the communion of His sufferings, being conformed to His death, if, by any means, I may attain to the resurrection from the dead. (Phi 3:8-11)

We confess that we believe in the resurrection of the dead. But in the journey of Lent, with St. Paul, we seek to become the resurrection of the dead. The living proof of our faith. We hear in St. Paul’s words, the heart of knocking, seeking, asking. He adds this thought:

Not that I have already attained, or am already perfected; but I press on, that I may lay hold of that for which Christ Jesus has also laid hold of me. Brethren, I do not count myself to have apprehended; but one thing I do, forgetting those things which are behind and reaching forward to those things which are ahead, I press toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus. (Phi 3:12-14)

This is the heart of the true science that is the love of God.

“Higher up and further in!”