Man is a creature of great depth, created by God, but after the Fall we are easily distracted from the depths, being enamored with mere surface appearances. What in our world today serves to distract us from the depths, and what can we do about it?

The present article is the second lecture to the series: “Prayer of the Heart in an age of technology and distraction” delivered by Fr. Maximos (Constas) in Feb. 2014 to the clergy of diocese of LA and the West of Antiochian of N. America at the invitation of His Eminence Metropolitan Joseph. The audio version of this lecture first appeared on Patristic Nectar Publications, and is published here by permission.

Fr. Maximos is the presidential research scholar at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of theology in Brookline, MA. He is an Athonite monk, one time professor at Harvard Divinity School, accomplished author and translator and lectures internationally in both academic and parochial venues.

* * *

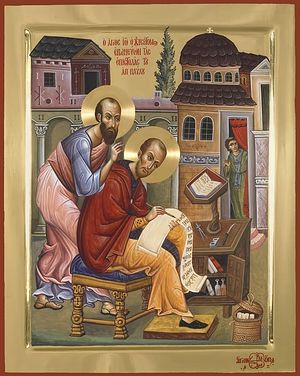

It’s hard not to hark back to the saint of the day—Isidore of Pelusium, for a very famous quote that merits repeating. Despite that he was an Alexandrian in the circle of the patriarchs who were no great friends of St. John Chrysostom, St. Isidore was a friend and supporter of St. John and actually reprimanded St. Cyril of Alexandria for his refusal to include St. John in the diptychs. In one of his letters he said, “The mouth of Christ is Paul, and the mouth of Paul is Chrysostom.” This reminds me of the tradition that St. John’s disciple Proclus, while St. John was locked in his study preparing his sermons, heard whispering from within the study. Perplexed because there wasn’t supposed to be anyone else in there, he peered in through the keyhole and saw someone leaning over and whispering into the ear of St. John. This continued for a few nights until St. Prochorus saw an icon of St. Paul and realized that he’s the one who’d been whispering into St. John’s ear. So St. Paul, in a sense, interpreted his own words through St. John.

Before we can talk about deeper things like the life of prayer we need to talk about what prevents us from a life of prayer, and one of the major obstacles in our path is the phenomenon of distractions. A few years ago I heard someone say in Greek something that was quite memorable: “Every depth has a surface, but not every surface has a depth,” and this is why we should not pay so much attention to surface appearances but rather to the depth of things. This is especially important for us as I see our culture becoming more superficial. We’ve lost the sense that there is a tremendous depth to life and to the human person, and everything has become very shallow and superficial and we’re now seduced and bewitched by surface appearances.

It’s all the more remarkable that people like us should have been seduced by surface appearances because in the history of civilization there have been no greater viewers of images than the Byzantines, the Orthodox. Of All people, the Orthodox were the most intelligent and sophisticated viewers of images. We live in a society saturated with images now and we’re not very sophisticated or critical viewers—we tend to be distracted by any passing image, and there are thousands of them everywhere. So, “every depth has a surface, but not every surface has a depth,” which is why we shouldn’t allow ourselves to become fixated on surfaces, but attend to the depths of things.

However, attending to the depths, is not easy, because we have a problem that prevents this from happening. The mind of man as we currently know it is a thing disordered, confused, and we find it hard to focus. We’re easily distracted. It becomes very difficult for us to get past the surface of things, so I think it’s within everyone’s experience that distractions take us away from our depth either by preventing us from engaging the depth altogether, or having found the depth they immediately pull us out of it, and out from the place of the heart, which is the core of our being, of our body. St. Gregory Palamas calls the heart the body within the body. Distractions pull us away from this and send us into exile. If we exist in a realm of distractions and allow ourselves to be pulled about by one sensation after another it will become increasingly difficult to get back to that body within the body, and we’ll live outside ourselves and become oblivious to the fact that we have a depth. There are people who don’t even understand that they have depth. “The original sin of the mind is distraction,” someone once said. Had Adam and Eve been able to stay focused on what they were told we wouldn’t be in the state in which we find ourselves.

How many times have you gotten up from your desk to go do something, and before you get there you’ve forgotten what it was? You arrive at some state of conviction about something and you feel strongly about it and you’re going to set the world on fire, and you walk out of the house and before you’ve gotten to the car you’ve forgotten what it was. This is the existential cognitive state we find ourselves in and it prevents us from attending to the depths. But we have to take this a step further: in addition to this general human condition or weakness, what have we done? We have built an entire culture of organized distractions, without parallel in the history of civilization. Try as you might to focus and stay on track, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to penetrate this veil of illusions that’s been dropped in front of our eyes. This isn’t really anybody’s fault in a personal way, but the fault of the culture in which we are socialized. We shouldn’t so much blame individuals for having difficulty focusing on their prayer life, for example—we need to look at the larger culture that has created this situation, which is increasingly reinforced by a range of gadgets and devices.

I was out of the country for about ten years and when I came back I almost didn’t recognize the country that I had left. When I left people had email but there were no smartphones or iPads and laptops were very rare. When I returned after a few years I was amazed at what had happened to society. Part of what a culture does is to naturalize itself and make you think this is what’s normal, and we get used to it. I was away so I wasn’t used to any of it. And it was surprising, and the degree to which we have become dependent on these technologies that for the most part just keep us distracted all the time was distressing.

Those of us who are older remember different times, but younger people find this all very natural and normal. I find it very unnatural. Even secular people are beginning to realize it’s very unhealthy. I can remember before TV’s had remote controls and you had to physically get up from the couch and walk over to the TV set, and because we’re so lazy we often watched something we didn’t want to watch. Now people have hundreds of options on the remote control and they channel surf. We bounce from one thing to another. We can’t rest even in entertainment, which should be recreative and relaxing. It’s not just that we flit restlessly from channel to channel, but what we see in the places we stop is itself highly fragmented and disorienting. On one channel there are even split-screen images, and there’s four people talking at the same time and there are two or three lines of text moving at different speeds along the bottom of the screen. We’re expected to attend to this range of very superficial chatter, and we’re told by the culture that this is multitasking and it’s a societal virtue, but I see it just as more fragmentation. I don’t think multitasking is a virtue.

This was the case when music videos first became popular, and I was astounded when I read that no single image stays on the screen for longer than three seconds. I didn’t believe it because it seems impossible, and now that style or aesthetic, if it even is one, is everywhere—movies and TV shows are like this, because our ever-diminishing attention spans demands a constant shifting of the kaleidoscope, lest we wonder from the screen for a minute. This is another thing that I find so distressing and it angers me and I wonder what it’s going to take for the Americans to rise up and say “Enough!”

It’s amazing how quickly people have adapted to this, and I find it very odd and distressing. St. Anthony, one of the great desert fathers says that there will come a time when the whole world will go crazy and there will be a few left who are not crazy and the crazy ones will look at them and say you’re crazy. If a priest were to get up in his parish and ask questions about technology his people would say he’s backwards, and medieval, and anti-technology. We’re afraid to stand up to the culture, when in fact there is no shortage of secular thinkers, not even Christians, who are raising red flags. Yet we’re not, because we’re in fear of the dominant culture, I suppose. There are thoughtful intelligent voices out there sounding the warning bells, and I think it’s in our best interest to pay heed.

Growing up we used to read newspapers in the house, and now they’re harder to find. The rise of the internet has had a very negative impact on journalism. The text of the newspaper is literally surrounded by advertisements, all of them literally screaming for your attention. There are ever-new methods of attracting your attention. It’s a struggle just to focus on the text in front of you, and I think that the result of this is to scatter our attention, to diffuse our concentration, and to blunt the quality of our awareness and perception. It’s very hard to focus now. It was never easy to focus, but it’s harder than ever now because of the technologies that we’re talking about.

I read a book called The Tyranny of E-mail. The argument was that language is a very beautiful and profound thing. The ability that we have as humans to communicate with one another is a fascinating, mysterious, and beautiful. Think about the desert fathers—“give a word”—not “text me a message”—but bring forth a word from your inner depth so that I might receive something life-giving. This book argues that email debases communications and imposes very narrow constraints on both the sender and receiver, by reducing communication to a very narrow medium, and a certain number of words. You send me an email and I feel the pressure to respond. You probably felt pressured to send me something. Now in the corporate world if you don’t respond within eleven seconds, the studies say, you run the risk of insulting someone or losing a contract. Communication is now being forced—we’re forced to say things we wouldn’t normally say at all, or at least say otherwise. We’re forced to respond prematurely and thoughtlessly. I don’t need to spell all of this out because it’s a part of our experience now.

Think about speech, language, logos—there’s something about the word and our words that are innately connected to God Himself Who is the Word. Soul speaks to soul through the medium of language. In the life of St. Symeon the New Theologian it says that when he was done reading from Scripture he would press his eyes to the page to touch the words on the page of the book, as you see people do with icons. The words are icons, verbal representations of meanings. We’ve lost that sensitivity because words and language have been debased, largely due to the technologies that we’re talking about here. Think about the Socratic Method and the whole idea of doing philosophy through conversation, through dialogue, that is dia-logos. For Socrates and Plato the idea was that truth was something much more democratic, that two or more had to come together and through this dialogos, through the give and take of ideas, the logos of truth would emerge. It’s much more beautiful, like a Synod in a sense. We don’t say that any one Church Father is the beginning and end of all things. It’s in the conciliar process that the word of truth can emerge or arise.

During Lent we read the prayer of St. Ephraim eight times a day and it says “give me not a spirit of idle chatter”; and what is so much of our communication electronically if not a lot of idle chatter? The gadgets we have enable a lot of communication, but what is the nature of what is being communicated; what is the quality? It’s often the case that less is more, and more is something nothing at all.

In a book by Mark Bowerlin called The Dumbest Generation he reports that the shift to reading online has begun to impact the way we read. We don’t read the words in a book in the same way as on a screen. Book reading means moving the eye from right to left, line by line by line. That’s not how we read information on a computer screen where the pattern is more f-shaped, where you look for a heading and then jump down and the eye goes into the paragraph—which is why everything is bulleted now. Perhaps part of it is simply the sheer quantity of data that we have to get through every day. But try going back and reading a book after that. For those of you who work with younger people you’ll see that this linear way of reading has been compromised and it’s difficult for many younger people to sit down with a book somewhere quietly and read through it. For one, it requires enough of an attention span, and much of what they are learning simply militates against that.

Worst of all is the so-called smartphone which I like to call the dumb phone, which is essentially a portable computer. I was with my family for thanksgiving and everyone came into the house with an iPad under his arm, and they literally had them sitting on the table and would check them every now and then. It’s very rude; it’s very divisive and destructive of community. And you might say, “Fr. Maximos you’re just a monk, and you’ve been living in a cave somewhere. Welcome to the real world—this is the way it is.” The news is that there are a growing number of secular psychologists and theorists offering very serious and pointed critiques of this technological culture because it is just so destructive of attention and concentration and human relation. So it’s not just monastic obscurantism saying these things. It’s something deeper and more widespread that we need to be concerned about.

Even in the seminary I see clergy in the altar serving with iPads. This is appalling to me. A liturgical book is a sacred object. An iPad is not, and it’s never going to be. I suppose if someone had a dedicated iPad that was for use at the chanting stand that might be okay if necessary, but this is not the same. These are the same iPads that people watch movies on, and what kinds of movies? These things have multiple uses, very few of which are even remotely sacred, and yet we bring that into the sanctuary? It’s distressing especially because it’s not necessary. If you’re a priest, learn when to come out of the altar and what to say. And if you haven’t memorized it, then open up the book. How odd to see someone in ecclesiastical vestments in the setting of a Byzantine church with this device.

Last year I was at an international conference on St. Maximus the Confessor in Belgrade, and it was a wonderful program. One of the many highlights was the consecration of a brand new church dedicated to St. Maximus. It was the first ever dedicated to him in Serbia. Met. John Zizioulas was there and ten other hierarchs and twenty or thirty clergy. It was a smallish church and it was packed, and a beautiful day. At one point prior to the start of the Liturgy someone came out of the altar and told me that the metropolitan didn’t have his Archeiraticon, so he ran out in a hurry because they needed the prayers for him to read. After a couple of minutes he came running back in because he had found the prayers on the internet and had them on an iPad. This altar was fairly open, by the way, so you could see into the sanctuary. So he came running back in with the iPad, happy that he had found the prayers, and as one body all of the Serbian hierarchs took a step back and said “No! Do not bring that object into this space.” It was done even without thinking. So he left and they printed out the text in the church office. It was a memorable thing to see that visceral response on the part of the hierarchy.

The next thing I wanted to talk about is about ADD/ADHD, because these diagnoses are up 70% in the last decad—for unknown reasons, we’re told. In 2010 there were over 10,000,000 cases reported in children for an illness that didn’t exist until 1987. Of course as a result of these diagnoses, kids at increasingly younger ages are being showered with drugs like Ritalin and Adderall. Brains that have not been fully developed are being bombarded with chemicals. This is certainly not a disease like the flu. It’s not genetic, which means it’s not simply a personal problem but a societal problem. It’s not a condition simply of the self but of the culture as a whole.

As a bridge to the next talk, why are we drawn to surface appearances? Why are we so easily distracted? Why are we addicted to surface appearances? What is it about the depth that frightens us? There’s something about the surface that we obviously love, because we’re forever clinging to it. Are we afraid of something that we might find there? Freud said people walk into a room and put the radio on right away because people don’t want to hear their unconscious impulses. Are we running from something? Or are we afraid that we’ll find nothing?—that we’ve become hollow, vacuous people, living on the surface, and to look into the void of our own nothingness is so terrifying that we welcome the distractions.

Society creates the problem, and then it offers us a supposed cure. You’re lonely, isolated, and fragmented? Well of course, because society has made us that way. But society is very kind so it offers a “cure”—endless television watching, endless distractions. We’ll help you cope with your inner nothingness by giving you these illusions. We have lived most of our life on the surface or outside or far form ourselves in a fruitless search for meaning and fulfillment. There’s a deep disconnectedness from ourselves going on, which means that we’ve become disconnected from neighbor and above all from God, and there are things that unmoored us from that deeper anchoring, be it trauma or something else.

And the final point: this is why the Church has always emphasized the importance of the inner life which is not about surface appearances. We don’t have photographs of the saints in the Church, even though we have saints who have lived in that time. We don’t consider photographs to be suitable for the iconostasis because the photo is the surface, while an icon reveals the depth. The ideal of inner attention, of recalling one’s fragmented and scattered attention, of recollecting oneself within the mind and then following the breath to the heart is the only solution we have for what’s happened to our society over the last ten years—and this serves as the bridge to the next talk.

This is a very important message and I would like to share the text on facebook.

Can you make this possible?

God bless!

Christiane Wilmes, Germany