Translation is tricky business. One word can mean the difference between heaven and earth, between a spiritual reading of Holy Scripture and a much more worldly reading, about, for example, the Babylonian Captivity.

After the death of Solomon in 931 BC, the Kingdom of Israel split in two. Ten of the twelve tribes of Israel formed a northern kingdom centered on Samaria, which lasted for 200 years before falling to the Assyrians. Two tribes, Judah and Benjamin, formed a southern kingdom centered on Jerusalem and called the Kingdom of Judah, which lasted for 130 years more before falling in 587 BC to the Babylonians, who laid siege to Jerusalem, destroyed the city and its temple, and carried off its people into captivity along the Euphrates River in what is now Iraq.

Much of the Old Testament was written during this period of exile, including Psalm 136, a song of lament sung by those who have lost everything except the memory of their kingdom:

By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion.

On the willows there, we hung up our harps. For there our captors required of us songs, And our tormentors, mirth, saying,

“Sing us one of the songs of Zion!” How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?

If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither!

Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you,

if I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy!

We sing this psalm at Vigil in the weeks leading up to Great Lent, but mark how differently we understand its meaning. For the Jews in captivity, the psalm expressed the extreme bitterness of their worldly misfortune. Indeed, the psalm ends with curses for their enemies:

Remember, O Lord, against the Edomites the day of Jerusalem,

How they said, “Raze it, raze it! Down to its foundations!”

O daughter of Babylon, you devastator! Happy shall he be who requites you

with what you have done to us!

Happy shall he be who takes your little ones

and dashes them against the rock!

These verses, especially the last one, sometimes trouble people. A sensitive young choir director once took it upon herself to omit the last verse—and was rightly rebuked by her rector for doing so. Why? Because such words challenge us to find the deeper meaning that eluded the Jews.

The Jews understood the psalm literally, thinking that their salvation lay in their return to Jerusalem. That was their hope during their years in exile. They did eventually return to Jerusalem and rebuild their temple, but their dreams of earthly glory did not come true, and they were left still waiting for the Messiah.

For Orthodox Christians, the Messiah has already come, and so we read the Old Testament very differently—in the light of Christ. For us, Psalm 136 refers not to any particular people, place, or situation, but to the estrangement of all mankind from God on account of sin. “Babylon” is our captivity to sin; “Jerusalem” is the Kingdom of God, in which we find freedom from sin and fulfillment in Christ.

Some fathers carry the allegory further, saying the “little ones” of the last verse are the demons that tempt us, or the passions that trouble us, or the little evil thoughts that sometimes occur to us in an instant but which we quickly put out of mind. It hardly matters. What matters is that our sins are the cause of our estrangement and our misery. (That’s why the Jews were in Babylon: They had ignored the warnings of the prophet Jeremiah and revolted against Nebuchadnezzar.)

Unfortunately today, some American Protestants miss this important point on account of faulty English translations of the First Epistle of the Holy Apostle Peter, in which the Apostle refers to Christians as paroikous kai parepidēmous—“strangers and pilgrims” in the King James Version [I Peter 2:11], pilgrim coming from the Late Latin pelegrinus, meaning “foreigner”—in other words, people who live here but are not from here. The Apostle’s point is that Christians are not at home in the fallen world, as the Apostle Paul says elsewhere: “Our citizenship is in heaven” (Phil. 3:20); “Here we have no lasting city, but we seek the city that is to come.” (Heb. 13:14)

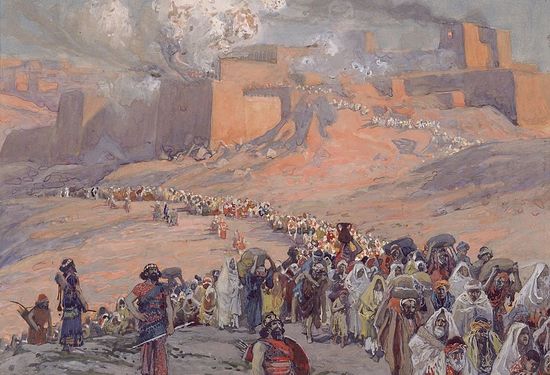

James Tissot, The Flight of the Prisoners, 1896–1902. Gouache on board, The Jewish Museum, New York.

James Tissot, The Flight of the Prisoners, 1896–1902. Gouache on board, The Jewish Museum, New York. The words paroikoi and parepidēmoi have also been translated into English as foreigners, sojourners, wanderers, visitors, outsiders, immigrants, aliens, refugees, and even “temporary residents.” Russian Bibles use words with very similar meanings: пришельцевъ and странниковъ in Church Slavonic; скитальцам, пришельцев, and странников in the New Russian Translation (Новый перевод на русский язык). (See 1 Peter 1:1 and 2:11.)

But many new English Bibles translate paroikoi and parepidēmoi as “exiles”—very wrongly, we must say, for the difference between exile and all the other words is that an exile is not merely a foreigner but a foreigner forced to live away from home. This slight difference has caused some leading American Protestants to read 1 Peter in the Jewish way, understanding the Apostle politically instead of spiritually. They now speak of their changed situation here in the United States as a “Christian exile” in which Christians are now captives of an ungodly culture and government, just as the Jews were captives of the Babylonians.

The Greek Old Testament does refer often to the Jews in Babylon as aichmalōsia, meaning “exiles” or “captives” (from aichmē, “spear point,” whence acme). But nowhere in the New Testament is the word aichmalōsia applied to Christians generally. Nowhere are they said to be “exiles” or “captives.” Quite the opposite: Just as Christ has trampled down death by death, He has also “led captivity captive,” freeing us “from the law of sin and death.” (Eph. 4:8, Rom. 8:2, cf. Psalm 67:18)

We are not, therefore, captives of this world, enslaved to sin, compelled by circumstances to participate in its evil. Neither are we exiles from the Kingdom, driven by God out of His presence. We are free men and already citizens of the Kingdom, responding to God’s call to return home and willingly suffering the trials and persecutions we encounter along the way, knowing that nothing can keep us from the Kingdom except our own sins.

Lent is part of our pilgrimage. It is a time to remind ourselves of our true home, lest we become too comfortable in this one. It is a time to take stock of our lives so as to separate our few essentials from the things we must leave behind. It is a time to pack up the things we will need along the way and to set out on the road for the next stage of our journey, so that tomorrow will find us closer to home, so that at the end of our lives we can arrive in the New Jerusalem on time, on the Eighth Day, the Day of Resurrection.

From Parish Life, a monthly publication of the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, Washington, DC, April 2016.

"And acme (pinnacle, peak) is a direct transliteration of akme, not aikhme, even though both words have similar meanings."

"The Greek Old Testament does refer often to the Jews in Babylon as aichmalosia, meaning “exiles” or “captives” (from aichme, “spear point,” whence acme)."

Captives, prisoners, under bondage, yes. Exiles, no. There is no shade of meaning of "exile" or "outcast" in the word aichmalotos or its cognates. And acme (pinnacle, peak) is a direct transliteration of , not , even though both words have similar meanings.

It is a valid and necessary point to make that translations of scripture must be accurate - but Dcn Patrick then makes the sort of error he has decried.