As we begin to enter into the practice of the Jesus Prayer to engage the presence of the Spirit within ourselves we began to encounter both passing and deeper, recurring thoughts that work to distract us from calling upon the name of the Lord. What is the origin of these thoughts, and what do they show us about ourselves and how we interact with the world? How does the Church teach us to deal with distracting thought as they come to us, and make room for Christ in our hearts?

The present article is the sixth lecture in the series: “Prayer of the Heart in an age of technology and distraction” delivered by Fr. Maximos (Constas) in Feb. 2014 to the clergy of diocese of LA and the West of Antiochian of N. America at the invitation of His Eminence Metropolitan Joseph. The audio version of this lecture first appeared on Patristic Nectar Publications, and is published here by permission.

Fr. Maximos is the presidential research scholar at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of theology in Brookline, MA. He is an Athonite monk, one time professor at Harvard Divinity School, accomplished author and translator and lectures internationally in both academic and parochial venues.

* * *

My overall focus in all of the talks has been the practice of the prayer of the heart and its foundations. The prayer of the heart is one of the most beloved and powerfully transformative prayers of the Orthodox Church. It’s not insignificant, but perhaps the most important thing we can do in terms of Christian practice.

I began in the first talk by speaking about distractions, which are the chief obstacle to prayer, especially for us in this society and in this day and age. Rather than support a life of prayer our society keeps us perpetually distracted and erodes our ability to concentrate, compromises our ability to focus, and all of these things rob us of our ability to be present and in the moment. We’re always somewhere else at some other time thanks to these technologies. How can we not just survive, but even flourish spiritually in the face of these increasingly invasive technologies and distractions? On the one hand, society has given us the tools for its pseudo-enlightenment, and the Church on the other hand has given us the means to true enlightenment, which is the practice of inner attention, the custody of the mind and the heart, not allowing it to be penetrated from all the things from outside—which is the practice of the Jesus Prayer, outlined in a definitive way in the Philokalia. My second talk concerned the beginning of the solution, the Philokalia and its history, which I find fascinating. As it says in the Bible, You are teachers of Israel and you don’t know these things? If we don’t massively appropriate the tradition for ourselves, who’s going to? The most important thing in the second talk was the traditional path of entry into the Jesus Prayer, because as we said you can’t just read the book chronologically.

The map for turning into the inner world is given in the Jesus Prayer, which is not navel-gazing mysticism, or some esoteric practice of people living in mountain fortresses. All of the teachers of the Jesus Prayer have recommended the practice of inner attention and vigilance of the heart as an essential Christian practice for all. The Jesus Prayer is a deep and direct engagement with the Holy Spirit within us. The third talk was on the buried seed; it’s not about relaxing your mind and relieving stress. These dividends will be had, but the primary reason to undertake this discipline is for no other reason than to engage and cultivate the seed, as the Church Fathers call it, of the Holy Spirit that was planted in our heart at Baptism. So I talked about the Biblical basis for this material and some Patristic texts.

The next talk covered some specifics regarding the Jesus Prayer such as what one does to concretely practice it, and how one says the prayer, what are the forms of the prayer, and especially how the prayer is connected to one’s breathing. The overall structure and movement of the talks has been straightforward, from superficial distractions to an inward, deeper engagement with the grace of the Spirit and the Jesus Prayer which is the art of cultivating that grace.

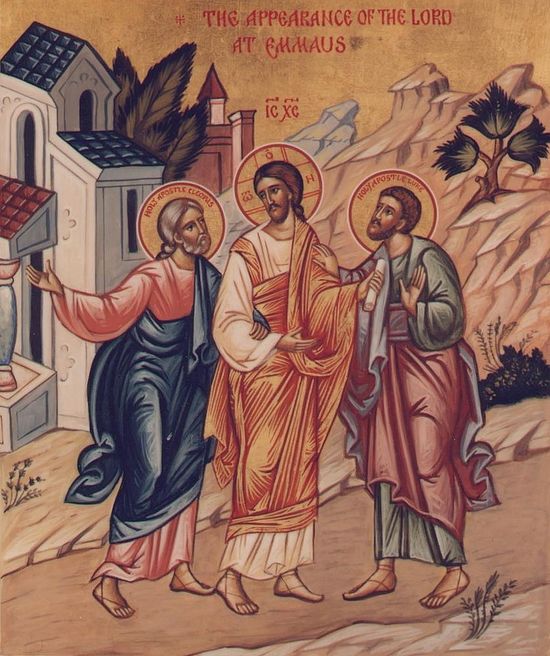

I would like to briefly say something about Luke 24:13-3—the walk to Emmaus, and especially verse 29: stay with us for it is towards evening and the day is now far spent, in order to make some obvious connections. I’m intrigued by the phrase it is now towards evening, and the day is now far spent—there’s a bit of melancholy, belatedness, sorrow, and regret there. Night is coming when no man can work. If we look at our culture we hear and see the signs of our late stage of western civilization. Is this the dying gasp? I don’t know, but to many it seems so. People talk about late capitalism, post-modernity, post-racial, even post-Christian. There is a sense of it being toward evening and the day having been far spent. And if the larger historical and cultural lateness doesn’t do anything for you, I see a lot of white hair out there—it’s towards evening for us. The meridian of our youth has long passed and we’re entering the twilight of our later years. Have mercy on us O Lord, have mercy on us. Think of all the verses about the time that was wasted and the precious little time that is left. On the Holy Mountain at Pascha time we say, “Christ is Risen! And here’s to next year!” And will there be a next year? My father died on Holy Thursday this past year—he didn’t live to see that Pascha. Fr. Seraphim Rose said, “It’s later than you think.”

That verse in Luke is a very rich source for this kind of thinking. But even more importantly is the request to abide with us, because night is coming. There’s something almost tragic in that, but also very beautiful in the acknowledgement that Whoever this is with us, He’s someone that we want to be with. Clergy are like the disciples, walking on the road; and it’s the walk of our life. We drag each other down. They’re not building each other up—they’re yammering and kvetching. And then Jesus shows up as a stranger and asks what they’re talking about, and because they’re in the state that they’re in they don’t recognize Jesus, and they mock Him—“What? Are you the only person who doesn’t know what’s going on? Are you living under a rock?” This is what happens. Rather than building one another up we drag one another down, and when Christ appears we don’t even recognize Him, we make fun of Him.

But that’s the surface. Something deeper is going on. Were not our hearts burning within us? Our hearts know things long before our minds do, and it takes time for them to catch up with us. I was outside and far away and not attending to myself. The language of abiding is very profound and widespread in the New Testament and especially in the Gospel of John where it’s a major motif—abide in Me and I in you, and the vine, and it’s in Paul too, to live in Christ. It’s a profound ontological statement about the indwelling of God in man and men in God. We are to be in Christ—it is no longer I who live but Christ within me. The seeds of grace in Paul grew to such proportions that it wasn’t even terribly clear anymore who was who and what was what. The “I” remains, but the seed grew into the fullness of the stature of the maturity of Christ within Paul. There was a mingling, and where the life of Paul ended and where the life of Christ began was hard to discern. This is why he can be so bold as to say Be imitators of me—not because Paul is special but because the life of Christ is alive, active, and vibrant within him.

The Church knows of no better way to abide in Jesus than to invoke His name constantly, and thereby also invoke and be in His presence. What better way to abide in Christ and become a tabernacle for the Divine Name, to have Him abiding in you and you abiding in Him? Is the point to accumulate wisdom, data about theology and Church history, or is the point to become transparent to Wisdom? I can fill myself with theories and ideas and knowledge and say clever things, but so what? That’s not what we’re about. Now it’s pointless anyway, because any information can be Googled. If all we give our people is something they can find on the internet then we’re giving them nothing—it’s just information. It needs to be more than that. The idea is not to fill ourselves with book learning, but to empty ourselves of the thoughts, especially the dark and impassioned thoughts, distractions, co-dependencies, resentments, and so on, so that we can’t say there’s no room in the inn here because I’m all filled up with dirty animals. The communion prayer says, “I have no place for you in me because I am fallen and miserable and wretched.” If those stables can be cleansed, and I can let go of all that stuff I’m holding onto, then there’s openness and now the grace of God can be manifest in my life, and through me it can be made manifest to other people. This is what it means to be the light, and to let the light from God so shine before men. The problem that many clergy have is that they’re in the way of their own work. Everybody has virtue and goodness and the presence of God in them, but the accident that is ourselves gets in the way of that and we often say things that hurt people and turns them from the Church. We need to get out of the way and let God do His work—to have a purified heart, mind, and soul so that the light of Christ passes through you and illumines those around you. That’s what we’re about.

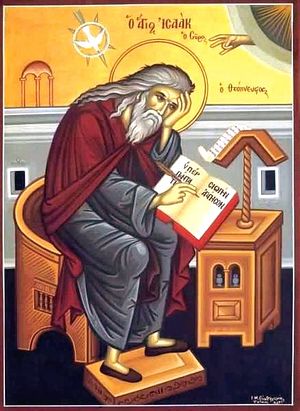

I have been in the presence of various people who change something in you just by a look. You feel moved to pray and you don’t know how it happened. One of the younger monks came as a visitor many years ago. He was in a rock band at the time and had no interest in the Church—he just went to Athos with some friends because it was the cool thing to do. He came to the monastery after Pascha and he saw a little old monk sitting in his stall holding his Paschal candle—not talking, just sitting. Seeing that image of a life devoted to God, someone who had sacrificed everything to live with God, the idea came into his mind that that’s what he wanted to be. Not a word was said, no books were read. No conversation was had. But that man had transparency through the grace of God. St. Isaac the Syrian says that when the virtuous man speaks, grace is communicated through his words to the listener. That’s also true if the virtuous man is silent. Everything he does—his moves, his gestures, the way he sits, the way he eats becomes transparent to the grace of God. And not too many years later that young man became a monk in that monastery. The older monk had died, and the young man received the name of that older monk. He literally became that man. That’s who he wanted to be and that’s who he became.

Keeping mind the progression of the talks, the next thing to talk about is that if we realize the distractions are a problem and we realize the Kingdom is in us by the grace of the Holy Spirit given to us in Baptism, and that the Jesus Prayer, that inner vigilance, is a wonderful and speedy way to engage the grace of the Spirit, we will very quickly encounter what spiritual writers refer to as “the thoughts”, or in Greek “logismoi,” usually meaning dark and negative thoughts—anger, desire, resentment, etc. We will encounter these obstacles as we seek to engage the grace of the Holy Spirit within us. A quick definition: St. Maximus the Confessor in The Chapters on Love makes a distinction between things in the world and their mental representations. Gold, for example, is a natural mineral, but the mental image that I develop about gold and money and wealth is something very different. The one is free, created by God, but this is an impassioned image and thought that I become fixated upon. His other example is a woman’s face. Like the gold, the woman is a beautiful, natural creation of God, but I can have an idea of woman, or I can have particular types of women in my mind that distort the way that I experience real women. For laypeople, their spiritual struggle is with the actual objects—not to steal, not to commit adultery. But for monastics our struggle is with the thoughts, according to St. Maximus. Everything in the world began as a thought, and in all of the vicious things that we do there is a thought backing them, an impulse that we did not check.

If I sit down to say the Jesus Prayer I will very quickly have certain kinds of thoughts running through my mind, usually very simple distractions such as “I think I left the oven on! I should leave my prayer and go check,” or “I forgot to call my mother,” or “I just got a great idea for a sermon!” All these superficial distractions are the first thing that happens to us. For many of us this is enough to break our communion with God because we consider our business and work more important than our intimacy with God. We have to realize and accept that this is what will happen. Sometimes you do remember something that’s so important you won’t be able to not stop and write it down, but you should just let them go and tell yourself that if the idea was so great and important then God will bring it back to you. Where’s our faith in God? Let the car get a little wet—the window probably isn’t open anyways. Let’s not allow ourselves to be dragged from that place of prayer that is so difficult to get to anyways. We have to be on guard about this.

All of these thoughts and memories are thieves because they steal the idea of God from the mind. And not just the obvious bad thoughts, but even allegedly good thoughts are thieves at that moment. St. Basil in a letter to St. Gregory the Theologian says that recollection of God is the indwelling of God. When we invoke the name of the Lord it is already the presence of the Lord and the indwelling of the Lord within us. To step away from that, from the throne of grace and the face of Christ because the oven might be on … we know what we should do. We’re only talking about a matter of minutes. I’m not saying forget the world for days at a time—maybe fifteen minutes. But these little things come in, and even fifteen minutes is too long for us. We’ve lost the capacity to stop and be still. We only feel comfortable when we’re multi-tasking.

If we continue on this path we will learn how to deal with and not even engage these simple distractions, but we will also begin to encounter deeper and more obsessive thoughts. There are certain images that continually recur, certain patterns of thoughts, certain faces, certain memories that are deeply imprinted in us—the kinds of things that go through your mind when you’re dozing off and you lose a little of your rational control. What are these things that are there? They’re part of something deeper within us. They’re not just thoughts or concepts, but they’re images that are filled with a dark energy—angers, resentments, lusts, that normally we don’t want to see and we’re in denial about. Those things are there and we avoid them with all the gadgets. But on this path we will come into contact with these thoughts and places where we’re not free, because, “whenever that person’s face comes to mind my blood pressure rises and I remember how angry I am at that person from twenty-five years ago.” People in my family have gone to their graves unreconciled because when they saw the face of that other person all they saw was that bitter memory. This is where a spiritual guide is important, because it is a difficult thing to stir up your psyche like this and encounter these dark things. You need some support of wisdom by someone who has been down this path and knows how to deal with it, and you need to know that this is natural and expected and part of the plan.

The other thing we need to know is that these obsessive, recurring and impassioned thought-feelings are not you. Maybe they happened to you, or they’re places where you were wounded, but they are not you. I think most of us from an early age in life make the fatal mistake of self-identifying with those impulses. I told you the story about the colleague who had insulted me and the thought of anger was there. The fact that I could even see that thought shows you that it’s not absolutely one with myself. I could look at it, hear it and see it. The fact that I can differentiate such thoughts from my own thoughts shows that there’s a difference. I could have just uncritically said, “Well, anger came in—of course, because I’m an angry guy.” I could have just embraced that impulse and thought and run with it; and if I’ve been doing that my whole life it becomes me. I think that’s who I am. All kinds of other thoughts and desires and inclinations are not us. But they can become us if all we do is welcome them and magnify them, and allow them to unleash their dark energy within us. I think all of us have seen these things. Unchecked, many of these thoughts can lead to neuroses of various kinds, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and at their worst, various sociopathic kinds of behavior.

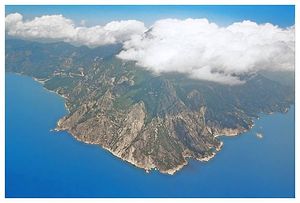

It always intrigued me that in Greece there seemed to always be a little cloud settled on the peak of Mt. Athos, and sometimes it’s a perfect saucer shape. The monks call it the “veil.” I always wondered what was happening meteorologically, and of course it’s very simple. The warm air moves across the surface of the ocean and hits the wall of the mountain, and it has nowhere to go so it rises and condenses and forms into a cloud. The mountain is a weather-maker. I thought, this is a profound image, because you are the mountain, you are not the cloud, but we make the mistake of self-identifying with the cloud. You’re not the emotional storm in your mind—that is other than you. It has come to rest on you, but don’t they come and go? Our job is not to follow them wherever they go, but to be rooted in the mountain that we are. During a storm, what is the most active part of a tree? The outermost part. If we live up here in our minds we’ll be agitated and blown about by every breeze. When we recognize that, it is the time to turn our attention to the core, the trunk, and not to self-identify with those thoughts.

There have been times when I was in line to receive Communion, and some of the most horrible, dark, even blasphemous thoughts came into my mind. Is that me? Why would I think such things, that I’d never thought before in my life, when my entire self is concentrated on receiving Communion? It breaks my heart even to know that I had such thoughts. I feel so bad that I have wounded God in some way. The pre-Communion prayer says “I stand before the doors of Thy temple, yet I do not put away evil thoughts”—is that us? Some people think they need to leave the line at that point, but we should simply make the sign of the Cross, ask God to forgive us, bemoan the fact that our humanity is corrupt and fallen, and hold our ground.

I had a student that walked to school every day and had to cross a bridge. Psychologically she was very healthy, but every time she crossed that bridge a voice came into her mind and told her to jump off. When I was sharing ideas like this she was so relieved to understand that that thought was not her. Another story: Years ago when I was a young student in college, I went to the Holy Mountain and spent time with an elder and his disciple in a small skete. We had to walk somewhere, and the elder who was eighty-five years old but spry as a mountain goat was in the lead, the disciple behind him, and I was in the back. We were on a path which was like a ribbon threaded on the side of a sheer cliff face. This path was about a foot-wide and on one side was the cliff face and on the other a thousand foot drop. We were walking along and at one point the disciple said, “Elder, a thought just came into my mind and I’d like to share it with you,” and the elder said, “My child, tell me what it is.” I was shocked. He says, “The thought just came into my mind to throw you over the cliff.” My first reaction was, “Oh my goodness, don’t say that!” Don’t be transparent, don’t be pure, don’t be empty—keep those things inside and let them accumulate until you have a thousand thoughts about killing your spiritual father, and then you leave because you can’t stand living with him. The old man chuckled and said, “That’s just the devil telling you that because he knows if you kill me you’ll wind up in lots of trouble, and you’ll have ruined the rest of your life. And that was it. There was no resentment or fear from the spiritual father. There was openness, freedom, and lack of attachment. Someone else would be suspicious for the rest of their life. That’s why Mark Twain said that we all have secret thoughts that would shame the devil. I think to the extent that we live in denial of that reality we don’t live a fully human life, and we don’t engage with our deeper selves.

I could have an image of myself as deserving some level of treatment—I’ve gone to university, I have a doctoral degree, I’m published, I’m invited to conferences. You won’t put me a in four-star hotel, but in a five-star! I’m an Athonite monk, I wear robes. If you come along now and don’t treat me in a manner consistent with my self-image, and you insult me or affront my dignity and honor, what are you really hurting? Is it me, or is it the image? The simplest solution to this problem is to get rid of the image. We can widen this—a husband and wife have an image of each other that they expect one another to conform to, and any deviation from that image is cause for a fight. Parents have images of their children and want to live vicariously through them, and when they don’t meet the image they’re shocked and scandalized. If we have these images of ourselves and others, is there real relating going on? Am I relating to my true self if I have this image of myself? Are you relating to your spouse if that image is intervening? The answer, of course, is no. We’re not free to experience the person for who they are, and they’re not free to be who they are because we impose an expectation upon them. That’s another problem with the images in the mind.

What to do about this? We should never engage these thoughts or worry and fret about them. Don’t think there’s something wrong with you. Just continue about your business. How foolish it would be to be led about by your idle, stray thoughts. Don’t couple with them. There’s a sexual metaphor here in a lot of the Patristic literature. To unite with these things is to enter into a profound union with them. Tell yourself you’re a Christian and you will not touch these unclean thoughts that come into your mind. We hear about shattered communities because of some huge scandal, and they all began with a single thought. That’s why the custody and stewardship of heart and mind is so important, so as not to allow these things in.

This is the image of crushing the babies in the Psalms, and the Church Fathers use the image of a flame in your heart. It’s as if you’re in the forest at night, and all the critters are going to be drawn to the warmth and light of the fire. When you see the critter stick its head in, cut it off from the outset. Don’t think about your thoughts, and don’t think about not thinking about them. You can spend your life running in fear from them. Don’t think about them and don’t think about not thinking about them. Another image for this is that of the fly. If you’re sitting in your house and the windows are open, flies will come in. Thoughts come in and out of the windows of your ears and eyes and all your senses. If the room is swept and clean and in order the fly will make its circuit and go back out the window. But if the inside is unclean, and food has been left out, then the fly will come in and lay its eggs everywhere, and soon you’re infested with all these wild, upsetting and agitated thoughts. The modern edition of the story is the airport. Planes fly over even Mt. Athos, but they say, “We don’t build a landing strip.” We can be temporarily disturbed by the plane flying overhead but we don’t build a place for it to land. For many of us our hearts have fifty runways. We have to learn to accept that they’re part of our experience and just don’t pay them any attention. In the monastery we say that if a thought bothers you for a day or two, struggle with it, but if on the third day it’s still there then go tell someone. It’s when you hold onto a thing that it gets harder to reveal—I’ve been dwelling on this for twenty-five years. But after two or three days it’s not so hard.

St. Isaac the Syrian says that the dispassionate man is not the man who has no passions, but it’s the man who doesn’t act on them. I might have an impulse to anger or lust or anything else, but I must be committed to not act on them. When I’m angry I try not to speak at all. But some people have no impulse control. To be dispassionate is to not act on your passions, not to hope that someday God is going to scrub all that stuff out of you. All those things will be there until the day you die in some form or another. The work from St. Hesychios in the Philokalia is one of the best works on the thoughts. It’s a series of short aphorisms dealing with different aspects of the thoughts. If you read those texts in order you’ll get to it at the appropriate time, and it will be very educational.

In English, as I said, we call these “thoughts”—but that might sound a little weak. What’s harmful about concepts or ideas? But it’s not just the mental equivalent of a word—it’s an image connected to an experience we’ve had. Imagine I had a terrible relationship with my father and I felt he didn’t love or recognize me, and it was impossible to please him. There are a lot of memories associated with my father, but there are feelings that go with these thoughts. Fifty years later if someone mentions him, I relive all of that pain, anger and resentment. That’s why I called it a thought-feeling. The thing inside me which generates that anger is still there, even if someone read a prayer of absolution over me. That mark is still there and there’s more work to be done. You’re forgiven for acting on the passion, but the passion itself remains. You’ve got to do more work to get through that, to really forgive your father from your heart, and understand better what happened.