Source: Anchorage Press

May 12, 2016

Father Aleksandr Yaroshevich’s face was still bleeding when he sat down at his makeshift desk to record the fight in his official journal. It was February of 1895, and for two years he had been the sole Russian Orthodox missionary among the Russian creoles and Dena’ina Athabascans of Cook Inlet, or the Gulf of Kenai as it was then known. Anchorage did not yet exist; Kenai was the main town on the Inlet, and had been for as long as anyone could remember.

Yaroshevich’s mission was headquartered in Kenai, but he was spending the winter at Knik with the hope of converting some Ahtna Indians from the Copper River who sometimes came down the Matanuska in winter to trade. It was a difficult time to be away, as he was deeply involved in the construction of a new church back in Kenai, but his parish was vast and he was the only cleric in an area that stretched from Prince William Sound to Lake Clark.

While in Knik, it came to his attention that an American miner named George Palmer had been living in sin with one of his parishioners, a Dena’ina woman named Pelagia Chanilkhiga. This, of course, was a much bigger deal in the 1800s than it is nowadays, and it was especially vexing to Yaroshevich because as the parish priest the spiritual life of his flock was something he considered very much his business.

Palmer and the one other American living at Knik—an Alaska Commercial Company (ACC) storekeeper by the name of Krison—felt differently on the matter.

According to Yaroshevich, Pelagia Chanilkhiga came to him one day and told him she did in fact want to marry Palmer, but that he would not consent to an Orthodox wedding. The young woman was clearly distressed over the choice she was being forced into. When word of this reached a local subchief named Afanasii Talchun, he took some men to the ACC store where Palmer was known to hang out in his spare time.

“Palmer and Krison started to shout,” Yaroshevich wrote of Talchun’s attempt to reason with the Americans, “saying that they did not want to listen to anybody and that they could live as they want and this was nobody’s business.” Palmer also made it clear that if the priest wanted to discuss the matter, he should be man enough to come and face him personally.

To be fair, Palmer did have a point. Alaska was at this time an American overseas possession (the official status of “territory” would not be attained until 1912), and Uncle Sam’s law was the law of the land, at least on paper. On the ground, though, Palmer and Krison and the handful of other Yankees living along the Gulf of Kenai were foreigners in a strange land. There was no police force except a U.S. Marshal based in Sitka; tribal custom and the teachings of the Orthodox Church were the law. Russian was still the common language. The overwhelming majority of residents were Dena’ina and Creoles, the latter being a mixed-blood hodgepodge of Russian, Tlingit, Athabascan and Aleut heritage who in former times had been citizens in full of the Russian Empire. Tsar Aleksandr III may have sold his North American colony, but the Orthodox missionaries were funded directly out of his successor Nicolai II’s pocket. One could even make the argument that through the proxy of the church, the tsar retained more influence in Alaska than did President Cleveland.

All of this, no doubt, stuck in the craw of the Americans. That evening after the argument in the store, Palmer’s “concubine” as Yaroshevich called her, came to him for confession. The priest, as duty required, reprimanded Chanilkhiga for cohabiting with the surly miner.

She must have voiced her trepidation to Palmer, for the following day he confronted Father Yaroshevich outside the cabin of a sick woman the priest had been tending to. Blocking him against the door, Palmer got right in the priest’s face. “What right do you have to interfere in the life of American citizens?” he demanded. “And what did you say to that woman yesterday?”

Yaroshevich told Palmer he had only counseled Chanilkhiga on what was best for her immortal soul by the teachings of the church. “Palmer,” he wrote, “who called me by the most disgusting words, which I do not want to reproduce here, grabbed me by the throat and using all his force punched me in my left eye.” And he kept on punching. He wore a ring that left a nasty cut on Yaroshevich’s cheek.

Krison, meanwhile, stood by, shoving aside the village men who ran to the father’s aid. Eventually they managed to overpower both Americans and drag Palmer away. The battered priest stumbled home, where his wife nearly fainted at the sight of his face. A few days later they fled Knik accompanied by a party of armed Dena’ina men. Krison’s name has faded from history, but Palmer would eventually have a town named after him.

The church Father Yaroshevich was in the middle of building was consecrated that summer as the Church of the Holy Assumption of the Most Holy Mother of God. When Dorothy Gray first arrived in Kenai 83 years later, she was pleasantly surprised to find this selfsame Orthodox church right in her new hometown. Now a retired schoolteacher, she’s the treasurer of a non-profit group called Russian Orthodox Sacred Sites in Alaska, or ROSSIA. Their mission is to preserve Alaska’s Orthodox churches, and keep alive the history associated with them.

Gray is the daughter of immigrants from what used to be known as Czechoslovakia, and was raised in the Orthodox faith. But when she started attending services at the Holy Assumption Church, it was impossible not to notice that the place was, to put it politely, falling into disrepair.

“Everything was wild and grown up around it,” she says. “The fence was falling down. It hadn’t been painted in a long time. The rectory was slowly sinking into the ground.”

In fact, the number of worshippers on Sundays had dwindled to a scant half-dozen. This was the 1970s, and American society at large was becoming more secular. The Cold War was in full swing, and the Russians were officially The Bad Guys. The old Dena’ina and Russian Creole families seemed to feel a need to distance themselves from the Slavic part of their heritage.

“I can remember the church was always the most beautiful building in our town,” Gray says of her childhood in upstate New York. Her people were factory workers. Money was tight. But whenever the local Orthodox church needed something, out came the wallets. It really started to bother her that the Kenai church was in such terrible condition, so she got together with the few remaining church members and started mowing the lawn, just to make it look like someone cared about the place.

The city of Kenai celebrated its bicentennial in 1991, and the manager of the visitors’ center at the time approached Gray about including the historic church in the festivities. Around the same time, historical architects from the National Park Service got interested in the project. Part of the NPS mission is looking after historic sites, and given the church’s status as a National Historic Landmark, they started coming down to Kenai periodically to check on its condition, which continued to go from bad to worse. The walls had begun to bow outward from the weight of the roof, and it didn’t take a genius to see that a major structural overhaul was the only thing that could save the historic church.

ROSSIA was formed in 2002 with a board pulled together by former Bishop Nikolai. They asked Gray to serve as a representative from the Kenai Orthodox community. “I’m not sure if I volunteered, or if I was volunteered,” she laughs.

After Seward’s Purchase, most of Alaska’s Russian buildings were either sawn up for stove wood or left to rot into the ground. The churches, however, stand as a palpable symbol of the Alaska that once was, a colony that looked not south to Seattle and east to Washington, D.C., but west across the whole of Asia to Moscow and St. Petersburg. This culture persisted even after the United States took possession in 1867, as George Palmer certainly found out. There are several churches ROSSIA has been working to save, including the St. Nicholas Church in Juneau and the Ascension of Our Lord Chapel in Karluk on the south end of Kodiak Island, the latter of which is by all accounts about to wash away into the sea. All the same, the board made the decision early on to focus much of its immediate attention on the Kenai church. It was a pragmatic PR move: The Holy Assumption Church is on the road system, and sees hundreds of visitors every summer. When ROSSIA applied for and received a Save America’s Treasures grant in 2006, the call was made to begin a full restoration.

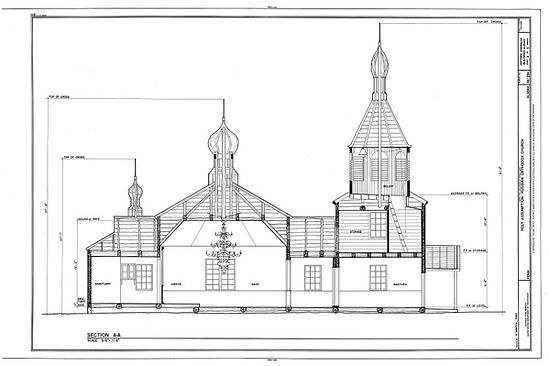

Father Yaroshevich undertook the original construction of the church in 1894 to replace an older church raised in 1849 by Father Nikolai Militov, the original priest of the Kenai Parish. When Yaroshevich arrived on the Gulf of Kenai in 1893, this older church was on the verge of structural collapse. He applied to the Holy Synod, the Orthodox Church’s governing body, for funds and was granted $400, no trifling sum at the time. Like most Russian buildings in the colony, it was built of hewn spruce logs, joined at the corners with dovetail notches. It was built in the Pskov pattern, a shape designed to be reminiscent of a ship, with the inherent metaphor of the church being a ship to carry the souls of the faithful over stormy seas. The original structure measured about 23 by 44 feet, a size likely determined by the length of the logs available in the area. Its original onion dome was tipped with the three-bar Orthodox cross. The lower angled bar represents the angled stub that Jesus’ feet were nailed to, and the topmost stands for the sign the Romans supposedly hung above his head that read Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. A two-story belfry was added to the north side in 1900, topped with another dome.

From the beginning, the Church of the Holy Assumption was meant to be the most beautiful building in town. It was built in an age when log construction was viewed not as an item of rustic frontier charm, but as a purely utilitarian method employed by poor people who lacked the time or the means to saw their logs into dimensional lumber. As such, the church’s log walls were covered with clapboard siding by 1910, then eventually with sheetrock on the inside. When all this was pulled away during the 21st century restoration, it revealed extensive rot around all the lower rounds of logs, and more rot high up along a window near the edge of the roof where the belfry joins the main church. It also revealed a layer of asbestos insulation.

Tearing into an old building is a lot like Forrest Gump’s infamous box of chocolates—you just never know what you’re gonna get. The asbestos was a surprise even to the NPS architects, whose business is to know these things. “It set us back about $36,000,” says Gray.

The bedrock principle of historic restoration is that original material removed from the structure must be replaced in-kind, this being preservation lingo for the idea that you have to do the reconstruction with materials that are as close to the original as possible. Exceptions are made for obvious health and safety issues like the aforementioned asbestos, but there was still a lot of in-kind work to be done. ROSSIA brought in professional log builders to cut away the rotten log sections and replace them with fresh-hewn spruce. The logsmiths also collected an enormous pile of sphagnum moss from the nearby forest that was used to chink the new log segments, just as was done in the original construction.

They even used wooden pegs to fasten the new logs in place, but when it came to truing up the bowed-out walls, the only option was to install a network of steel rods and plates that could be tightened up to suck everything back into shape. Historical architects design this kind of stuff all the time, and the rods were hidden in the floor and ceiling, thus preserving the historical appearance of the church, even if the in-kind authenticity had to be fudged a little for the sake of structural stability.

Most recently, ROSSIA constructed a small mechanical building immediately to the west of the church, designed by NPS architects to look like an old structure that might always have been there. The church, which still functions as the community Orthodox church, needed among other things a real bathroom. Back in the day, you could just walk out to the edge of the woods or to a neighbor’s outhouse when nature called, but times have changed. The building also houses much of the new fire-suppression system that will soon be installed. Unlike conventional sprinkler systems, it will used pressurized steam to snuff out any fires before they truly get going. The cost is estimated to be north of $300,000, and there’s still more work to be done. Truing up the walls seems to have opened some minor leaks in the roof. Then there’s more paint and wallpaper, all of which must be matched as closely as possible to the originals.

Still, it’s a small price to pay to preserve a building that has stood witness to so much of our history.

Back in 2008, when Sarah Palin made her ill-advised comment about being able to see Russia from her house, the world got so stuck on this dubious bit of hyperbole that it missed the rather obvious point that the very ground upon which that house stands was once Russian soil. Cook Inlet was one of the more heavily Russianized areas of Alaska, and despite a century or more of neglect, our Russian continues to peek out from beneath the current veneer of Mom, the Flag, and apple pie. The roots go deep, for anyone who cares to look. The city of Wasilla, over which Palin once presided, was named for the Dena’ina Chief Wasilla. This name was an Anglo mispronunciation of the name Wasili, which in turn is how the Alaska dialect of Russian pronounces the name Vasili. (Alaskan Russian, according to linguists, lacks the /v/ consonant, replacing it with a /w/ at the beginning or middle of a word, or an /f/ at the end). Vasili is the Slavic version of Basil, a name associated both with the comedy of John Cleese and with St. Basil the Great of Caesarea, born in what is now Turkey in 330 AD.

Vasili, or Wasili, happens to have been one of the more common boys’ names in Russian Alaska during the period when the Chief was born. Indeed, well into the twentieth century, many Dena’ina spoke Russian as a second language, while for Creoles it was their first. Even as late as the 1980s, Russian-born anthropologist Lydia Black was astonished when she met Dena’ina elder Shem Pete and found that he spoke excellent Russian, albeit with a thick colonial accent.

You wouldn’t know any of this if all you had to go on was the accepted narrative of Alaska’s Russian past, namely that their time here was nothing more than 120 years of unmitigated rape, pillage and environmental destruction that left nothing behind but a smattering of place names and a slew of illegitimate half-breed children.

History, as Henry Ford once said, is mostly bunk, and this is a prime example. Modern day Alaskans are conditioned to believe that our history began with gold and salmon, that Alaska was nothing more than a tabla rasa for Americans to write the 20th century version of manifest destiny. We are masters at embracing our collective amnesia when it comes to anything preceding the Stars and Stripes, the old photographs or grubby prospectors and their bushy moustaches. Seventy-odd years of Cold War propaganda may have drummed out any semblance of nuance with respect to the old Russian days, but the history—meaning the real history, not the standard party line—is still there for any who care to look.

Father Yaroshevich never did see his finished church. After the fight with George Palmer, he and his family were transferred to Juneau at his own request. But the Palmer incident was only the beginning. There had been a gold strike on the remote backwater of Turnagain Arm. Salmon canneries had recently been built at the mouths of the Kenai and Kasilof rivers. More and more Americans were arriving on every inbound ship. The culture of the Russian Creoles and the Dena’ina would soon be plowed under to become a sort of shadow society existing in parallel space with the new Americans.

But the Church of the Holy Assumption still stands. It reminds us that the Russian language was still the lingua franca of Cook Inlet for many decades after the purchase, even as the Creoles who spoke it went from being privileged citizens to invisible half-breeds. It is a reminder that race and class struggles are by no means some distant problem left behind when one moves north from the Lower 48. It’s a reminder that the namesake of the town of Palmer was the kind of asshole who would beat up a priest, which in turn calls to mind the fact that for all the things that are fine and good about America, there are still plenty of ugly things in our history that we as a nation have yet to come to terms with.

One thing still keeps shocking me. How perverse is the Western idea for democracy, fraternity and equality. During the "despotic" Russian tzar the native Alaskans were 100% Russian citizens, without any restrictions. During the American "democratic" regimen the natives that are the people of the land are not considered American citizens. The ideology of WASP exceptionalism is rediculas.