On May 29, the Orthodox Church remembers the Fall of Constantinople, the Queen of Cities, in 1453. Named after Saint Constantine the Great, Constantinople was the capital of the Byzantine Empire (330-1453). Although Byzantium’s vast power spanned 11 centuries, its story is often held hidden.

In his 2006 book, Sailing from Byzantium: How a Lost Empire Shaped the World, Colin Wells describes it:

The successor of Greece and Rome, this magnificent empire bridged the ancient and modern worlds for more than a thousand years. Without Byzantium, the works of Homer and Herodotus, Plato and Aristotle, Sophocles and Aeschylus, would never have survived. Yet very few of us have any idea of the enormous debt we owe them.

More than just the cultural, economic and political core of Eurasia, Constantinople was the center of Christianity. Three of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, for example, were held there: the second in 381, the fifth in 553 and the sixth in 680.

Moreover, the Emperor Constantine presided over the First Ecumenical Council and also halted the formal persecution of Christians with the 313 Edict of Milan.

(To commemorate its 1,700-year anniversary, the Ecumenical Patriarchate—the center of worldwide Orthodoxy,[1] which to this day has its See in Constantinople—organized an international seminar to discuss religious freedom. His All-Holiness Bartholomew, Archbishop of Constantinople-New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch, opened the conference with a discerning and insightful keynote address.)

Throughout its history, the Byzantine capital was sought after: by Persians and Avars in 626; by Arabs in the seventh and eighth centuries; and, by Russians (who had not yet converted to Orthodoxy) in 860. Each time, however, Constantinople was kept in Christian hands.

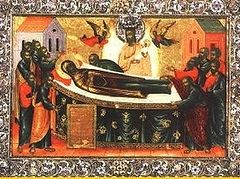

After the City’s first deliverance from its enemies, a hymn to the Most Holy Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary was composed as thanksgiving for her protective intercessions in keeping Constantinople safe. The emotionally stirring and deeply loved prayer (Ti Ipermaho, in Greek) is chanted by Orthodox Christians during Great Lent:

Unto You, O Theotokos, invincible Champion, Your City, in thanksgiving ascribes the victory for the deliverance from sufferings. And having Your might unassailable, free me from all dangers, so that I may cry unto You: “Hail! O Bride Ever-Virgin.”[2]

What therefore happened in 1453 that allowed Mehmet II, surnamed the Conqueror, to capture the Queen of Cities? In his “Prologue of Ohrid,” Nikolai Velimirovic, a 20th century Serbian Saint, says that “Because of the sins of men, God permitted a bitter calamity to fall upon the capital of Christianity.” Some say that the Union of Florence, a failed attempt to reconcile western Christendom with Orthodoxy, was one of those sins.

On April 2, 1453, Mehmet and his men reached the city walls; though different estimates of forces exist, a compromise figure is that defenders totaled 10,000, while the attacking force was 250,000 strong.

Despite assorted offensive strategies, the Greeks defended Constantinople for seven long weeks. The resilience and fighting ingenuity of the Greeks frustrated the sultan but in the end it was not enough.

Shortly after dawn on May 29, 1453, the splendid city of Constantinople was taken.

“For three days and nights,” as the Great Synaxaristes of the Orthodox Church describes, “the sultan allowed his men to plunder the city … Property of priceless value, works of art, precious manuscripts, holy icons and ecclesiastical treasures were destroyed.”

Once ensconced in power, Mehmet was not too unkind to Christians. In “The Great Church in Captivity,” Sir Steven Runciman, an eminent British historian and Philhellene, describes how the “Sultan was wise enough to see that the welfare of the Greeks would add to the welfare of his Empire.”

After the Monk Gennadios was confirmed as Patriarch (he, along with Grand Duke Loukas Notaras, had led the Church’s anti-Unionist party), Mehmet himself was present at the investiture. Runciman describes how the “Sultan handed [Gennadios] the insignia of his office, the robes, the pastoral staff and the pectoral cross.” A mosaic depicting this exchange hangs in the entrance of the Patriarchate today.

Mehmet famously declared, “Be Patriarch, with good fortune, and be assured of our friendship, keeping all the privileges that the Patriarchs before you enjoyed.” This declaration highlights the importance of, and need for, religious freedom, including for the present Ecumenical Patriarch in his ability to exercise his ecclesiastical authority without interference.

While the Fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, the Ecumenical Patriarchate persevered; and while the Fall ushered in a time of martyrdom and persecutions for Orthodoxy, the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church still carries on as the beacon of Truth.