A very apt word for the world we live in is: disenchanted. It was first used by Max Weber and a number of others to describe a certain aspect of the modern world – the absence of the sacred. Where people of earlier eras and other cultures have experienced the world around them as charged with divine power (of various sorts), we simply experience the world as inert. There is nothing there.

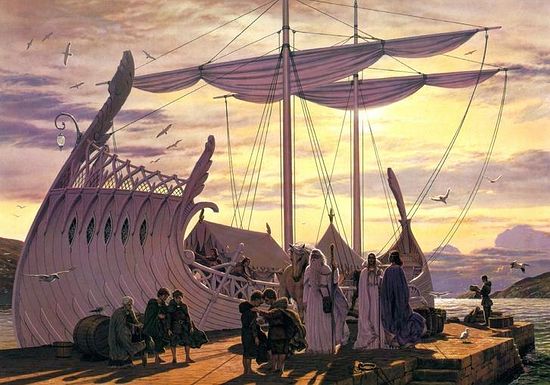

The disenchanted world is doubtless a major source of modern atheism. When someone says they do not believe in God, they are quite likely simply relaying accurately how they perceive the world – that the world they see is simply disenchanted. This experience is captured by Tolkien in his hints of the end of Middle Earth. The “Elves are heading West,” leaving the world of Middle Earth. The Age of Elves is coming to an end and the Age of Men is beginning. There is something of a hint that with the Elves, the world of magic and wizardry is leaving as well. The new dangers will simply be the will and work of men rather than larger, darker forces.

Of course, that is Tolkien’s mythic tale, but it echoes a sense of the world that surrounded his generation. Like Lewis, he was a veteran of the Great War (WWI), where soldiers first encountered the nightmarish horrors of modern warfare. Battles of that war sometimes left the dead numbering in the hundreds of thousands, even exceeding a million. It surprised even its generals. And with the advent of such horrors, what remaining innocence that preceded the war (and there was an abundance) simply disappeared.

The forward march of disenchantment has not ceased. For Tolkien, the emigration of the Elves is stated in mythic form. For us, the mythic forms themselves have departed along with every enchantment. I recall a walk in the woods with my children when they were young. We came across a “fairy circle,” a circle of mushrooms in a small clearing. I called it by its mythic name. My 3rd grader quickly interrupted me by pointing out that “there are no such things as fairies.” I was crestfallen – mostly because my child had already lost her sense of enchantment by age 9.

How do disenchanted Christians deal with the world as sacrament? Within broad reaches of Protestantism, the sacraments themselves were long ago disenchanted, reduced to mere ceremonial reminders of a theologoumenon. They eat and remember, or baptize in obedience, but nothing happens. Not only is the world disenchanted, but for some among them, the world must be disenchanted as a matter of dogma.

There have also been manifold modern efforts to render the sacraments more relevant, more meaningful (meaning “less enchanted”), even within Catholicism. The Mass as a locus of democracy, devoid of alienating mystery and complex ritual, validates democracy, but only succeeds in reducing the Mass itself. Tragically, everyone already believes in democracy – it’s God that they cannot believe. There are clearly many who are unhappy with such directions and consider such efforts to be a disaster. But the damage may have already been done. Can the world, once disenchanted ever be restored to its former wonder?

I think about this, often long and hard, and far more often than I would like to admit. As an Orthodox priest, I stand in the “enchanted” altar and the beauty of Orthodox liturgical life. But the Elves left my world a long time ago. For though I stand where I do, my perceptions have been deeply damaged (!) by the disenchantment of the age. But like many others, I stand and watch, catching the occasional glimpse of an Elven footprint.

I look at the disenchanted creation (we must even struggle to call it a “creation”) and remind myself of its true existence. This creation is no accident. It has order and meaning. It has structure and coherence. The world in which I wonder has such narrow parameters in its construction, that the slightest alteration would have rendered the whole thing nothing more than a boiling lump or, yet, nothing at all. Things only exist because they exist inprecisely this manner. And that fact carries with it a shimmer of magic – or should, unless you have the disenchanted mind of modern child.

And the Christian witness is that the very anthropic principle of the universe becameanthropos and spoke. The enchantment of the world became a man. And that Man took bread and said, “This bread is my Body.”

I often think that the disenchanted perceptions of modern man have nothing to do with what he sees and everything to do with the myth of disenchantment. Modern man sees the Bread just as well as the enchanted Apostles themselves. Only the Apostles were told about the enchantment of bread and believed. The modern man sees the enchanted bread and doubts – because he thinks that surely – enchanted bread would look somehow different. As it is, it looks like – bread.

What should enchanted bread/body look like? Should it hover in mid-air or shimmer with some ethereal effervescence? Should it’s taste suddenly bring a warmth of divine strength flooding every fiber of a disenchanted body?

St. Philaret of Moscow described the true enchantment well:

All creatures are balanced upon the creative word of God, as if upon a bridge of diamond; above them is the abyss of the divine infinitude, below them that of their own nothingness.

Every existing element of creation shimmers with being, standing as sheer miracle in its very existence. And if the Truly Existing One declares, “This bread is my Body,” then it cannot be otherwise. The disenchantment of the world is a spiritual failure to see the truth of existence. Wonder has been exchanged for weariness and the mystical metamorphosed into the mundane.

The battle of Modernity is not with our eyes but with our hearts. The failure of wonder hardens the heart destroying our capacity for giving thanks. Fr. Alexander Schmemann said, “Anyone capable of giving thanks is capable of salvation.” It’s opposite is also true. The giving of thanks, the eucharistic existence (eucharist=thanksgiving), is at every moment the true apprehension of the universe and its relationship with God. And it is the wondrous, sustaining grace of God that is the ground of all thanksgiving. The priesthood fulfills its existence when it cries aloud, “Let us give thanks unto the Lord our God!”