It is not at all easy to distinguish the borders between periods in the fluid and unbroken element of human life. Moreover, the incommensurability of successive historical cycles is quite manifestly revealed. New life themes come to light, new forces start to make themselves felt, new spiritual centers form. Someone’s very first impression is that the late fourth century signifies some indisputable boundary in the history of the Church, in the history of Christian culture. Someone may conditionally define this boundary as the beginning of Byzantinism. The Nicene era closes the previous epoch, and a new epoch begins in any case: if not with Constantine (d. 337), then with Theodosius (emperor 379-395). It attains its zenith, its acme under Justinian (emperor 527-563). The failure of Julian the Apostate (332-363, emperor from 361 to 363) testifies to the decline of pagan Hellenism, but only its decline, not its eradication.

The epoch of Christian Hellenism has begun; it is a time when people try to construct Christian culture as a system. And this is a time of painful and intense spiritual struggle. In the disputes and disquiet of earlier Byzantinism, it is not difficult to identify a common fundamental characteristic theme. This is the Christological theme, which is at the same time the theme of a man. Someone can say that what was really being discussed in these Christological disputes was the anthropological problem, for it was a dispute over the Saviour’s humanity and receives human nature over the sense of how the Only-Begotten Son and the Logos [or Word] and thus over the sense and limit of human life and activity. It is perhaps precisely for this reason that Christological disputes attained such an exceptional poignancy and dragged on for three centuries. In them, there were revealed and laid bare, a whole multitude of irreconcilable and mutually exclusive religious ideals. These disputes ended with a great cultural and historical catastrophe—the great defection of the East. Almost all of the non-Greek East broke away, dropped out of the Church, and retired into heresy. If one accepts the late fourth century as a boundary, as the end of one epoch and the beginning of Byzantine theology proper, then more is involved, for Byzantine theology not only cannot be properly understood without understanding the theological controversies of the fourth century, without understanding the legacy of the fourth century. There is more. The legacy, which Byzantine theology was to inherit, cannot be understood properly without an understanding of the entire legacy, which it inherited. And there is a special concern, for Byzantine theology—indeed Byzantium itself—has been understood but little in the West.

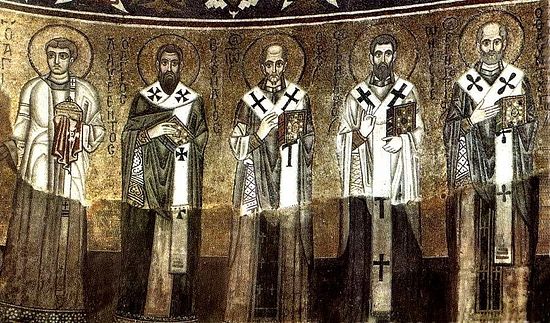

For several reasons, Western Christianity somehow keeps pace even if inadequately with some of the Greek or “Byzantine” fathers of the fourth century—in a strictly historical sense Byzantine theology begins in 330, in that year when the city of Byzantium was inaugurated, was christened Constantinople, “New Rome.” Those theologians writing in Greek after the year 330 can indeed be considered “Byzantine” theologians. However, as the decades and centuries flow onward the Latin West appears incapable of keeping abreast with the vital work of Byzantine theologians. True is there is usually a small circle of persons in Rome who have contact and some knowledge of Byzantine or Eastern theology but this circle is limited and their knowledge fragmented. It was a sore tragedy for the history of Christianity, for the life of the united Church, that this drift took place. There were certainly political and cultural reasons for the drift, and, often, the blame can be placed on Byzantium. Nevertheless, in the realm of the Church, in the realm of theological thought, in the realm of vital issues, concerning the essence of the faith such a drift should never have occurred. In modern terms, someone could say that Byzantium and Byzantine theology has had—and largely still has—a “bad press” among Western Christians. Moreover, included in this “bad press” is not only an atmosphere of contempt for the Byzantine East but also a grave ignorance and lack of understanding. Byzantine theology was engaged in a struggle for the preservation of the truth—it was engaged in vital theological issues just as St. Athanasius and as the Cappadocian fathers in the fourth century were. Western Christians kept abreast with the thought of St. Athanasius and the Cappadocians, but it must be regrettably acknowledged that even that knowledge is not complete, that somehow ineluctably a curtain partially closes and prevents Western Christians from dealing with and understanding the totality of the thought of St. Athanasius and the Cappadocians.

It is not only a brief survey of the salient elements of fourth century Eastern theology necessary for a proper understanding of Byzantine theology but also necessary an overview of certain patterns of thought in the earlier Patristic era. And it is almost scandalous that even a brief overview of Christological thought in the New Testament is a prerequisite for an understanding of Byzantine theology precisely to demonstrate that Byzantine theology is organically related to the original deposit of the truth of the faith, that Byzantine theology is, as it was, a Biblical theology and not a fabrication of sophistry, that Byzantine theology was dealing with burning issues of the Christian faith and of Christian life. The beginning of Byzantinism is not the beginning of a new Christianity. Rather, it is the legitimate heir of the legacy of the New Testament, of early Christianity, of the Apostolic Fathers, of the Fathers of Church.

The Christological and Trinitarian definitions of the Council of Chalcedony,—moreover, of all the definitions of the seven Ecumenical Councils—are not the result of philosophical intrusions into the Biblical vision of God but rather—and precisely—the explication of what was originally revealed, of what was originally deposited, of what was experienced by the earliest Christians: that Jesus was the Christ, the Son of the Living God, that Jesus was both true God and True Man, the God-Man, that God is God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.

The rationalism and, as it was, the arrogance of the eighteenth and nineteenth century scholars of the New Testament created more an exercise in exegesis than exegesis of the New Testament. And it has made the understanding of Byzantine theology even more distant to Western Christians. If the Christ of the New Testament is one and the same with the Christ of Byzantine theology in its ultimate victory over heretical thought and if the Christ of the New Testament has been misrepresented by schools of New Testament thought in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, some carrying over to the twentieth century, then the possibility of misunderstanding Byzantine theology is heightened, is increased. For this reason, it is necessary to present textual material from the New Testament precisely as a legacy inherited by Byzantine theologians, a task that should not be necessary and that would not have been necessary in most periods of the history of Christianity. The twentieth century has witnessed largely a reverse of this position—a considerable body of twentieth century scholarship on the New Testament has again discovered that the definitions of the Ecumenical Councils correspond to that truth present ab initio. There is no intention to present any comprehensive study of the New Testament. Moreover, there is no intention to present an exhaustive and comprehensive analysis of the Christology of the New Testament. Only some texts from various writers of the New Testament will be presented. These texts consist of those, which are explicit, and those, in which many do not discern the Christological implications. It is merely a sampling, merely an overview to set the basis of the background, the core of the foundation, in which and from which Byzantine theology worked. Moreover, it must not be forgotten that the Byzantine theologians were always conscience of being the heirs of the apostolic faith, heirs of the theology of the New Testament and the theology first delivered. They saw a continuous and cohesive link and bond between them and the earliest theology of the Church, between them and the Incarnation, Life, Death, Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus Christ, the eternal Only-Begotten Son of the Father. The very fact of the existence of the Christological controversies in Byzantium testifies that it was a vibrant and creative theological life rather than an ossified one. It is true that they also saw themselves as preservers of that faith once delivered, but in the very process of preserving that original deposit, they are of necessity creative.

From Georges Florovsky, The Byzantine Fathers of the Fifth Century.