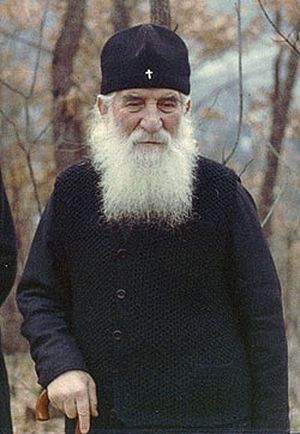

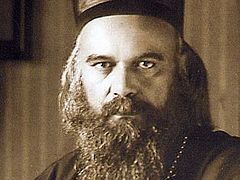

Saint Justin (Popovic, 1894-1979), a Serbian saint, was a theologian and archimandrite of the Celije Monastery. St. Justin was a renowned scholar on Dostoyevsky, an anti-communist, and a renowned writer. He was the son of a priest, from a family with a tradition of priests. He studied at the faculty of Theology at the renowned seminary school of St. Sava in Belgrade and graduated from there in 1914. At the seminary in Belgrade, he met hieromonk Nikolai (Velimirovic), Ph.D. (later St. Nikolai), who became his spiritual father and most influential person in his life. However, that does not mean that he had exactly the same views as his spiritual father, which we will see later on. St. Justin continued his studies in Russia, The UK and Greece. He studied many years in London, but his doctoral thesis, “The Philosophy and Religion of Fyodor Dostoyevsky” was not accepted at Oxford due to its criticism of Western society, Western humanism, rationalism and the Roman Catholic Church and its teachings (mostly what he saw as human-centric/anti God-man view on the papacy). However, this thesis was published years later when St. Justin became the editor of the Orthodox journal, The Christian Life, which he, together with his colleagues from Oxford, edited and published for twenty years. St. Justin translated many texts by the Church fathers into Serbian. After the Second World War, St. Justin was removed as professor from the Seminary in Belgrade and was under strict communist control at the Monastery of Celije until his death. Many, including Bishop St. Nikolai Velimirovic, had to flee the country; however, what perhaps “saved” St. Justin was the fact he was not a bishop, but a priest-monk. He was a very feared and powerful opponent of the communist regime, and played a large part in organizing the Serbian Church after the Second World War. He is also known, or rather presented, as a great opponent of ecumenism and in particular a critic of the Roman Catholic Church and what he considered their heresies, mostly the fall of the papacy, which he considered to be the third fall of man in history, after Adam and Judas. He is highly venerated as a pious and educated holy man who fought to keep Orthodoxy pure, who fought for the Church during Communist times, and as a spiritual giant that fostered many of today’s bishops and monastics in the Serbian Church.1

St. Justin was a puzzling figure during his lifetime, and remains so, more than 35 years after his repose in the Lord. He was himself never a bishop, which allowed him to speak and write even more freely and openly about the issue of ecumenism. It is very important to understand that while St. Justin was very hard in his descriptions of the Western Christian churches (especially the Roman Catholic Church), their, from his point of view, heresies and errors, he was a loving man of God. Many people have tried to use his writings against ecumenism to justify comments and behavior that is very unchristian and very fanatical, especially his thoughts about what he called “papism”2. But that’s very shallow and disrespectful towards the saint. Instead it is vital to look at the whole picture when analyzing his rejection of (a particular sort of) ecumenism. He was a deep spiritual thinker, as intellectually gifted as blessed with many spiritual gifts. While we read what St. Justin thought, we must look at it with the knowledge that he spoke the truth in very direct ways, in ways that are very harsh, yet he always remained loving towards all humans. He just despised sin. He saw heresy and schism as grave sins against Christ and his Church.

St. Justin never himself participated in any ecumenical meetings, but never critiqued participation in them as such. He knew St. Nikolai Velimirovic personally and his participations in these meetings, yet he considered him a saint even during his lifetime, as Bishop Atanasije Jevtic (spiritual son of St. Justin) writes3. I will here look into notes4 left by St. Justin about the topic of ecumenism. These notes are from the end of his life (1972) when he was writing his book, The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism, which is by many seen as a great analysis of ecumenism from the Orthodox standpoint. I will use here not so much that book itself, but instead the much more personal and raw notes that St. Justin wrote while writing this book. These notes have recently been published for the public in the book I am using and so offer a lot of new insight into the thoughts of the saint. They are seen not only as a base for his above mentioned book, but also as material that offers us a much deeper insight into the thoughts of the saint.

Meaning of the word “ecumenism” for St. Justin.

In order for us to even attempt to understand St. Justin, it is important to first and foremost know what the word ecumenism meant to him from an Orthodox perspective. The covering sheet of his notes stated: “The Orthodox Church = Ecumenism by catholicity (Russian: sobornost = “to gather”).”5 Let us for a moment focus on the understanding of the term catholicity/catholic (sobornost). The word is understood in the Russian sense of meaning,6 namely a “spiritual community of any jointly living people,” “to gather,” which has its core in the cooperation between people and the denying of individualism. The difference in the Western understanding of the word is almost non-existent, it is just important to understand that “catholicity/catholic” in this case has nothing to do with the Roman Catholic Church, but rather refers to the word “catholic” itself. The Western use of the word is often understood as “universal”, which can be seen as having the same or roughly the same meaning as the Russian “Sobornost”. Therefore: the “catholicity” of the Christian Church is about gathering all into one. Hence, the word “ecumenism/ecumenical” can now in this context be understood as St. Justin himself explains: “Ecumenism: The catholicity (sobornost) of heaven and earth, of God and man, the soul of universality, of evangelic and orthodox ecumenism: We live on earth but we store up for ourselves treasures in heaven (Matt. 6:20). Everything was the holy catholicity (sobornost); which lies in the unity of the theanthropic (Divine-human) Church = the God-man Christ the Lord. Body on earth, heart in heaven: Our wishes should be catholic; and they are such when they are holy (Matt 6:21). And man’s holiness is in God, more precisely: in the God-man. And in the Person of the God-man: God transfers all his attributes, including holiness, to man. Without God – man is a tiny mosquito (…) everything was created for the holy theanthropic catholicity and unity (Matt 6:25-34) (…) ‘Whoever receives you, receives me; and whoever receives me, receives the one who sent me’ (Matt 10:40). Therein = in Him the entire catholicity, the entire universality, the entire ecumenism. Where He is—all of those are present and more; the Entire Holy Trinity [is present]. Everything from Him and everything in Him! Everything towards Him.”7 The saint spends a lot of time deepening his explanation of ecumenism as he sees the Orthodox Church seeing it. But to show and explain it all would take up too much space. Instead focus has been put on the one that is at the core of all else—the one that is the foundation of St. Justin’s understanding of his own title: “The Orthodox Church=Ecumenism by catholicity”. Ecumenism is only real if it places the God-man in the center. The WWC statement from Amsterdam 1948 in a similar fashion states: “The World council of Churches is a fellowship of churches that accept our Lord Jesus Christ as God and Savior”8

Ecumenism and catholicity of the Church could only be true and correct for St. Justin if it was a theanthropic viewpoint, placing the God-man in the center of all things. “God-manhood is the fundamental catholicity of the Church (=ecumenicity, as the atom is to the planet): up to Triadicity: but through the God-man who both leads into and unites with the Holy Trinity: as the ideal and reality of perfect Catholicity (=ecumenicity) (…) Therefore the Church [is]: the most perfect workshop for the creation of perfect man. Everything else apart from the God-man: pseudo society and pseudo personalities—an unfeasible humanistic hodgepodge. Only: Christ [is] all and everything. By her very nature the Church is ecumenical, for she is catholic”9

9.4 Humanism and Ecumenism

Now that it is made clear what St. Justin means when using the words “ecumenism” and “catholic”, it is safe to move forward into his criticism of the ecumenical movement and of the whole of Western European society. This is important to do because St. Justin`s view on ecumenism is colored by his criticism of his contemporary world and the ecumenical movement of his time.

“Jesus is the same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb 13:8)—this is something that must be the core of the Orthodox understanding of ecumenism, according to St. Justin. In other words, we (humans) can’t change Christ, we can’t decide what he thinks about x or y. We can only put the God-man in center of everything and especially of ecumenism, and work from there. That is the only way for St. Justin, and a theme seen throughout his writings. The God-man solves all the eternal problems of man and mankind—no human can do that. Hence his critique of Western humanism. If the Church can’t solve the eternal problems (with the God-man Christ in the center) of mankind, “She sinks into petty humanistic and hoministic problems”10. This leads to the Church becoming earthy only. She kills people (St. Justin uses crusades and inquisitions as examples11), solving all earthy problems with earthly measures, namely with fire and the sword. This in turn, according to St. Justin, kills the God-man, it kills Christ who is the Church. The Church must follow the first two commandments of God: Love of God first and then humans, “From God to man: from the God-man to man”12. Humanism, however, always takes the reverse order according to St. Justin. This is something he calls “papal humanism”13, as he sees the Pope as the leader, cause and head of humanism (something we will get back to later). This “pan heresy,”14 as he calls it, leads to constant shedding of human blood in the world and the slaughter of human souls as a result.

St. Justin saw humanism as evil, pure evil and totally opposite to God, the Gospel and the Church. The source of this humanism and its entrance and increased influence in society has its roots in the papacy and the “infallibility” of the pope, according to St. Justin. St. Justin sees the pope as the model of the anti-Christian theory of “the ubermensch”. The fall of the pope, as well as the fall of Adam and Judas, the saint sees as the three biggest falls of mankind. St. Justin sees “papism” and its earthly and human power as the pan-heresy of humanism, as the putting of man before the God-man in the center, instead ending up where man is the measure of all things, and no longer God. St. Justin also sees the pope as the father of Protestantism, which he sees as the final stage of “papism”: “each [Protestant] believer – a self-appointed and separate pope”15 (This is why the term “papism” also for St. Justin includes Protestants, who according to St. Justin all consider themselves as popes.) By this he is referring to the fact that the pope is (in his understanding) held infallible in questions of faith according to how he understands the Roman Catholic teaching, while every human is infallible in understanding the bible in Protestantism, according to St. Justin`s understanding of these confessions. Both of these he sees as man-worship, humanolatry, scholastic and rationalistic bacchanalias. “Hence so many sects [Protestants]: it is actually all one, having been fathered by the pope, by his humanolatry and by his man-godhood. In opposition to: the God-man.”16 European humanism is essentially anti-human and equal to “papism”, according to St. Justin. Humanists have one soul: “a papistic-protestant soul”17. He calls the humanistic society of Europe the “mount Olympus of the Roman-Protestant Europe; Zeus=the Pope”18. Through humanism, the European man degenerates himself into a homunculus, a non-man. For St. Justin, at the heart of humanism lies rationalism, which he also sees at the heart of scholasticism: “For scholasticism and rationalism gauge everything ‘according to man’, by man; but man is incomparably more extensive than all this, in the same proportion as the God-man is more extensive than man”19

The cure for the “infallibility” that St. Justin considers demonic in character and for “the Hades of Roman Catholicism”20, is conciliarization (sobornost/catholicity) which is a self-humbling of man before the God-man, before the Mother of God and all saints; a repentance “that leads to a full knowledge of the truth” (2 Tim 2:25). Conciliarization is the means that is in the God-man and the only way to save ecumenism from its “second death”21, as it died the first time through “papism” and other humanisms, according to St. Justin. St. Justin is not addressing the historical primacy of the bishop of Rome,22 or denying the historical primacy in any way, he is simply referring to the papacy in a practical and ideological way in its post-schism time, that included some of the crusades which directly affected the Orthodox, the reformation, the counter-reformation, the enlightenment period and the two Vatican councils.

9.5 The branch theory—“denominationalist”

Another aspect of the western Christianity that the saint strongly rejected was the so-called Branch Theory (or as Peter Bouteneff calls it: “denominationalist”), which is very common in the Protestant world. The basic idea is that all Christian churches are different branches on the one Christian tree; they are part of the same body. St. Justin sees it not as branches of the tree of truth, but as fallen off and withered branches; “a branch withers if it falls off the vine” (John 15:6). The vine is for St. Justin the Church, the body of Christ, the God-man and the ultimate truth. By falling off from the truth, from Christ and his Church, a branch withers and dies. Therefore, he sees the western Christian movements as fallen away and withering, as heretical. This is important to understand; St. Justin sees the Roman Catholic Church and what he calls its offspring, the Protestant movement, as heretics. He often uses St. Mark of Ephesus to demonstrate it, who himself alone, according to common Orthodox opinion, saved Orthodoxy from a union with Rome (see: council of Florence 1439): “One who departs even by a little from the Genuine Faith is deemed a heretic and is subjected to the laws against heretics… Latins [Roman Catholic Church] are therefore heretics and we have cut them off as heretics” (Quote by St. Mark of Ephesus used in St. Justin’s note23). Being a heretic for St. Justin meant being separated from God and from the Truth. The branch theory was, according to St. Justin, a western innovation from the 16th century, and therefore he saw no organic connection to the early Church and to the teachings of the fathers and/or the Ecumenical councils. “As soon as man separates from him (the God-man)—he dries out, withers and dies. This is exactly what happened to papist, Protestants and all other heresies and schisms.”24 St. Justin’s understanding of “The branch theory” or “denominationalist” is very much in line with traditional Orthodox and Roman Catholic understanding. The difference is how St. Justin explains it and where he sees its roots.

St. Justin and Orthodox ecumenism—how it should be

It is very clear for us how St. Justin felt about Western Christianity, what he saw as the biggest problems and heresies. He has written countless more works about the falling away of the Western church and its heresies. However, here has been brought to light the core in his thought about this, his criticisms. Let’s now focus on St. Justin`s thoughts about how ecumenism should take place from an Orthodox perspective; because despite his sometimes very harsh writings about ecumenism and its participants, he was not totally against an ecumenical dialog. Bishop Atanasije Jevtic, one of St. Justin`s spiritual sons and the one that was closest to St. Justin, calls people that suggest St. Justin was against every kinds of ecumenism as “unwise zealots” and that they are blaspheming St. Justin by thinking that.25 Some critics of ecumenism claim that people’s efforts to find positive views towards the ecumenical movement in St. Justin’s thoughts are forced and out of place. It is, however, important to point out that people like bishop Atanasije are regarded as rather cautious or even negative towards ecumenism themselves, and many describe him (Bishop Atanasije) as ultra-nationalistic and conservative in a way which would exclude ecumenism almost completely. This is an indication that he would have no personal interest in portraying and defending St. Justin`s thoughts in any inaccurate way.

St. Justin calls ecumenism “The substance of the Church”26. This ecumenism is not the ecumenism understood and practiced today, especially in the Protestant world. For St. Justin, ecumenism is the way the apostles worked miracles by the Holy Spirit and in the name of Jesus. Ecumenism can only be practiced with and by the holy mysteries (that is, the sacraments) of the Church, with Holy virtue that “christify us and trinitize, divinize and sanctify us”27. This would again imply truth, being in truth, in the Church, as the main criteria for ecumenism. I think the way one might understand this is that all should go back to the roots of the Christian church; hence the apostles being mentioned, and from there work forwards, rejecting all innovations not accepted by the Seven Ecumenical Councils, the things that are not truth and that has caused division among Christians. Everything must be done through Christ and with Christ in ecumenism. The saint lists a few key fundamentals of ecumenism. I have divided them here into small categories as I saw fit.

-

Ecumenism is “Where two or three are gathered together” (Matt 18:20).

-

Ecumenism should be build/have its foundation “On the Holy Spirit”28. Like the apostles and the ecumenical councils, ecumenism must allow the Holy Spirit to act just as it does within the Church. The Holy Spirit is the Spirit of Truth.

-

Ecumenism can’t be about us humans; it can’t be anthropologic. As the apostle Paul preaches: For we do not preach about ourselves, but about Christ Jesus as Lord (2 Cor. 4:5). About the God-man and “Not about Paul nor Apollos nor Cephas—neither Luther nor Calvin”29. Instead we should preach the Gospel, which is not according to man. Humanistic Christianity is pseudo-Christianity. Every humanism is a heresy.

-

The only way ecumenism can work again, the only way out so to speak is through repentance “that leads to a full knowledge of the truth” (2tim 2:25). This repentance must come by humbling oneself before the God-man, before His Church, before the Theotokos and all the saints. St. Justin never, not even once, talks about repentance in an earthly way; he never seeks for forgiveness here on earth from heretics towards the Orthodox. Instead he always puts the God-man in the center of all; and because heresy is such a grave sin, forgiveness and repentance can only be asked from God and given by God – through his only begotten son the God-man Christ and his Church.

10.1 Conclusion

I have studied ecumenism from an Orthodox standpoint and its history. The Orthodox view on this subject includes many different opinions and is not expressed with one unified voice, as is the Roman Catholic view, for example. The history of ecumenism and Orthodoxy helps us understand and get a clearer picture of the involvement of the Orthodox in the movement. St. Justin and his thoughts shed a light on what some within Orthodoxy see as an issue, namely ecumenism as a humanistic ideology, which St. Justin argues was the type of ecumenism practiced in the WCC during his lifetime and clearly is the same type of ecumenism practiced today.

It can be argued that St. Justin`s view on ecumenism wasn’t very tolerant and loving, that it was very one-sided and ignorant. But apart from being a brilliant theologian and philosopher, he was firstly and fore mostly a real Christian, a follower of Christ. His love for all humans was remarkable and his humbleness was that of a real ascetic. His sometimes very harsh words about others were never aimed at the people, but at the sins they committed. St. Justin hated sin and saw what it can do to a human soul. Therefore, his harsh analysis of his temporary society is to be seen as a sort of prophetic undertaking, based solely on his love for his neighbor and deep desire that salvation be made available to all, as to fulfill the Lords commandment to make “disciples of all nations” (Matt 28:19).

When analyzing St. Justin`s critique of the ecumenical dialog, we can’t ignore his historical context. He spoke during the time of the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, who made several audacious statements saying that there was no real obstacle to the establishment of the unity of the Church, and that the issues and problems come from theologians and theology. Many in the Orthodox Church at the time of the meeting in 1965 between the Ecumenical Patriarch and the Pope, were not pleased with comments and actions of the Patriarch, e.g., Metropolitan Philariet of the ROCOR30, who sent the Patriarch a letter.31 This time was filled with more questions than answers, and people like St. Justin felt the need to clearly answer many of these questions. Bishop Irinej (Bulovic) of the Serbian Church, a spiritual child of St. Justin and an active member of the ecumenical dialog as representative of the Serbian Church, today states the following about St. Justin and his views: “I feel that voices like that of Father Justin, often harsh and critical, have ensured that the course of events should not take a different direction. Father Justin—this is how I understand it now after raising this issue with him often—never criticized the idea of dialogue, witness and love. He was himself an extremely open person. But he criticized the ideology of ecumenism, considered it a variant of the ‘new Christianity’, as an ecclesiological heresy. He felt that it is a dangerous heresy, and he even forged a new term, now widely used, that of the ‘pan-heresy’.”32 For St. Justin, ecclesiology and Christology were one and the same; hence ecumenism, being a question of Church, ultimately was for St. Justin a question about Christ himself. As Bishop Irinej (Bulovic) points out here, St. Justin was against what he saw as the ideology of ecumenism and not against dialog. He rejected the humanistic tendencies towards Christian unity where humans are put in the center, and not Christ. He wanted to substitute what he saw as the western idea of humanistic ecumenism with that of the evangelical and Orthodox ecumenism, where the God-man Christ is in the center and is the criteria for all. He built upon and elaborated some ideas by St. Nikolai Velimirovic (+1956) who, in the decades before St. Justin wrote down his thoughts, critiqued European civilization’s separation from Christ, and the presence of secular tendencies inside the Western as well as the Orthodox Church33. In the same way that St. Justin viewed Europe and its denial and rejection of Christ, he saw the Western churches putting Christ aside and inserting humanism, a human, into the center of the faith. Ecumenism and all-inclusiveness is the calling of the Church for St. Justin. In his fundamental idea of catholicity (sobornost), the foundation must be the all-inclusiveness of the Orthodox Church—an all-inclusiveness of the theanthropic ecclesiology for which Orthodoxy stands. As St. Justin puts it himself: “Ecumenism is a movement that generates a multitude of questions. All these questions in fact spring from and flow into a single desire for only one thing: the True Church of Christ. The True Church of Christ supplies, as it should, the answers to all the primary and secondary questions posed by ecumenism. For if the Church of Christ does not solve the eternal questions of the human spirit, it serves no purpose… Of all beings, man is the most complex and most enigmatic. This is why God came down to earth and became man… For this reason He remained in His fullness on earth in His Church, of which He is the Head and which is His Body. The True Church of Christ, the Orthodox Church: In it is the whole God-man with all His Good News and all His perfection” 34. This is St. Justin’s testimony on ecumenism. Only Christ can be the head of the Church according to St. Justin, and not a pope or any other human, even on earth as Christ is with us to this day within the Church and within the mysteries (sacraments) of the Church. It is known that St. Justin never broke communion with any Orthodox bishop or clergy that partook in ecumenical meetings, he never created any schisms or scandals, which is another clear indication that he was in fact for this dialog as long as it was undertaken in what he saw as the correct and Orthodox way, which is ecumenism in the theanthropic truth. His criticism of Western humanistic ecumenism was due to the fact that all it could lead to, according to St. Justin, was a false image of love. Love without truth is nothing, and this is the main idea of St. Justin. If we put the God-man in the center of all we do, the only Love we can get is Love in Truth, God himself. If we put man in the center of all, we will slowly wither and die, separated from God and his Church, according to St. Justin. The Orthodox Church as a whole has been very active in the ecumenical movement from its beginning. What is revealed to us in the study of the history of Orthodox ecumenism is the issues that are born out of a lack of one unified voice. The issue of representatives of the different churches that make up The Orthodox Church, expressing sometimes vastly different standpoints on questions that they should address as one. This creates the problems surrounding ecumenism in the Orthodox Church; and I believe that St. Justin answers these questions in a way that he considers to be the Orthodox way, the way that he considers the loving yet truthful way of the God-man.

Author’s comments

St. Justin’s critique almost never mentions dogmas or official teachings. He rather refers to what he sees as the ideology and philosophy of the western Christians. His arguments, one might say, are deeper than that of a systematic analysis of differences between the Churches. They are based upon the notion of a heresy secular in nature becoming an ideology within the Church. St. Justin was against the ideology of the Papacy as he saw it, not the Pope as a human, or any other human for that matter. I strongly believe that he was de facto an ecumenist, just as the Church is ecumenical. His theology and philosophy aimed at including all and everywhere into the Church that he saw as the Body of Christ. He did this out of love and not out of hate. Those who use St. Justin to fuel their fanatical and hateful attitudes towards the non-Orthodox are in my opinion misunderstanding St. Justin in a grave way. Truth and Love go hand in hand for St. Justin; to argue for the truth in a fanatic and hateful way in reality strips Love out of Truth. This I strongly believe St. Justin would see as a heresy, because Christ is Love and Christ is the Truth, not one or the other, but both and all in one.

You can read about the nature of ecumenism here:

http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/93492.htm

Does he mean that there are Orthodox who do not express themselves in a two faced hypocritical (sic diplomatic) manner as the western sophisticates do. Showing themselves to be superior and arbiters of Truth. Justice. Oh, and ''Love''.

So if a canonised Saint from my own nation by the name of Kosmas of Aitolos told people to ''curse the Pope'' knowing the heresies and perdition that this man would lead the gullible to, do the arbiters of right and wrong, hate and love, judge St Kosmas to be ''hateful''.

And again as another saint from my nation by the name of Paisios the Athonite in his Spiritual Counsels vol 1 laments in the chapter on common prayers:

''Unfortunately today, European ‘’courtesy’’ has arrived with Europeans attempting to present themselves as being ‘’nice’’; that is to show off their ‘’superiority’’– whose culmination is worship of the two horned devil - "One religion” they tell you should exist, and in doing so attempt to level out everything. Some Orthodox persons also come to me and say: "All of us who believe in Christ should create one religion". It’s as if they wish to mix gold and copper - so many carats of gold and that much copper. Is it correct to mix them? Ask a jeweller. Is it proper to mix trash with gold?''

Do they judge him to be ''hateful'' because of the way he speaks. What is hate? What is love? Pray do enlighten us.